Introduction

Maturity determination constitutes a fundamental aspect of postharvest management in horticultural crops. It involves assessing the physiological and biochemical state of produce to identify the optimal stage for harvesting. Accurate maturity assessment is critical because it directly influences essential quality attributes, including flavor, texture, color, aroma, and nutritional composition. Harvesting at the appropriate maturity stage ensures that produce meets both market standards and consumer expectations, thereby enhancing its commercial value.

Stage of maturity → Harvest timing → Postharvest quality → Marketability → Consumer satisfaction.

Significance of Harvesting at the Correct Maturity Stage

The timing of harvest plays a pivotal role in maintaining the overall quality and storability of horticultural produce. Crops harvested at the optimal stage of maturity display superior organoleptic properties, such as enhanced taste, firmness, and visual appeal.

Properly matured fruits and vegetables demonstrate uniform ripening, which facilitates effective postharvest handling, storage, and transportation. Moreover, adherence to correct harvesting schedules reduces mechanical damage and susceptibility to physiological disorders, thereby extending shelf life and marketability.

Implications of Inaccurate Maturity Assessment

Improper determination of maturity can lead to substantial postharvest losses and deterioration in quality:

- Immature Harvest: Crops harvested before reaching physiological maturity often exhibit underdeveloped organoleptic characteristics, such as poor taste, insufficient sweetness, and incomplete ripening. They are prone to shriveling, water loss, and reduced market value due to their inferior size and appearance.

- Overmature Harvest: Delayed harvesting beyond the optimal maturity stage results in overripe produce, characterized by reduced firmness, increased susceptibility to mechanical injury, and accelerated microbial decay. Overmature crops have a limited postharvest life and are unsuitable for prolonged storage or transport, leading to economic losses.

Necessity of Scientific Maturity Assessment and Harvesting Methods

To ensure the delivery of high-quality produce from farm to consumer, precise maturity evaluation and the application of scientific harvesting techniques are indispensable. Methods for assessing maturity include visual indicators (e.g., skin color, size), mechanical measurements (e.g., firmness, specific gravity), and biochemical tests (e.g., total soluble solids, acidity).

Adoption of standardized harvesting protocols minimizes human error, preserves quality attributes, and reduces postharvest losses. Ultimately, scientific maturity determination serves as the cornerstone of effective postharvest management and quality assurance in horticultural production systems.

Types of Maturity

I. Physiological Maturity

Physiological maturity refers to a specific stage in the life cycle of horticultural or agricultural produce when the plant organ, fruit, or seed has completed its natural growth and development processes. At this stage, the biochemical and structural development of the produce is considered complete, meaning that all essential physiological processes required for full development have occurred. Physiological maturity is often assessed by indicators such as seed development, changes in color, size, or firmness, and the accumulation of specific biochemical compounds like sugars, starches, or oils, depending on the crop type.

A key characteristic of physiological maturity is that the seeds within the fruit or plant are fully developed and possess the capacity for germination. This indicates that the reproductive function of the plant organ is complete, which is particularly important for crops intended for seed production.

However, it is important to note that physiological maturity does not always correspond to the stage at which the produce is optimal for human consumption—this latter stage is referred to as edible maturity. For many fruits, the edible quality, including flavor, sweetness, and texture, may develop only after harvest, through processes such as ripening.

Examples of Physiological Maturity

- Banana: Bananas harvested at physiological maturity are capable of ripening properly after harvest. Even though they may not be immediately edible, the internal biochemical processes allow for the development of the characteristic sweet flavor and soft texture during postharvest ripening.

- Mango: Mangoes reach physiological maturity when their pulp has fully developed in terms of size, sugar content, and nutrient composition, yet the fruit remains firm. At this point, although the mango may not be ready for immediate consumption, it has the potential to ripen to edible maturity if harvested and stored under appropriate conditions.

Understanding physiological maturity is crucial for postharvest management and harvesting strategies. Harvesting at the correct physiological stage ensures that the produce can undergo proper postharvest ripening, maintain quality, and reduce losses. In addition, for seed crops, harvesting at physiological maturity maximizes seed viability and germination potential, which is essential for agricultural productivity.

II. Commercial Maturity

Commercial maturity refers to the stage of a horticultural or agricultural produce at which it has attained the desired qualities for consumption and sale in the marketplace. Unlike physiological maturity, which is defined by the completion of growth and development at the cellular and biochemical level, commercial maturity emphasizes market-oriented characteristics such as size, shape, color, texture, firmness, and flavor. These attributes determine the produce’s acceptability to consumers and its suitability for handling, transportation, and storage.

The determination of commercial maturity is influenced not only by the biological development of the produce but also by external factors related to marketing and logistics. These include:

- Market demand: Different markets may prefer produce with specific characteristics. For instance, some consumers may prioritize sweetness, others color, or firmness.

- Transport distance: Produce intended for long-distance transport may need to be harvested at an earlier stage to withstand handling and shipping without quality deterioration.

- Storage facilities: The availability of cold storage or controlled-atmosphere storage can allow fruits and vegetables to be harvested slightly immature while still reaching peak quality at the time of sale.

Examples of Commercial Maturity:

- Tomato: For local markets where the produce can reach consumers quickly, tomatoes are often harvested at the breaker stage, when the fruit has just started to change color. This allows rapid ripening and consumption. For distant markets requiring longer transport, tomatoes are harvested at the mature-green stage, ensuring they remain firm during transit and ripen gradually to maintain quality upon arrival.

- Citrus fruits: Citrus are generally harvested when the peel color and total soluble solids (TSS) to acidity ratio meet consumer preference. These parameters reflect sweetness, juiciness, and visual appeal, which are crucial for market acceptance.

Commercial maturity is a critical concept in postharvest management because harvesting at this stage maximizes economic returns while minimizing postharvest losses. Harvesting too early may lead to underdeveloped flavor or appearance, reducing market value, whereas harvesting too late can result in overripe or damaged produce, affecting both shelf life and marketability. Therefore, understanding the interplay between biological development and market requirements is essential for farmers, exporters, and supply chain managers in ensuring high-quality produce reaches consumers efficiently.

comparison table between Physiological Maturity and Commercial Maturity

| Feature | Physiological Maturity | Commercial Maturity |

| Definition | The stage when the produce has completed its natural growth and development. | The stage when the produce attains desirable edible and marketable qualities such as size, color, flavor, and firmness. |

| Focus | Biological and developmental completion of the produce. | Marketability and consumer acceptability. |

| Seed/fruit development | Seeds are fully developed and capable of germination. | May or may not coincide with seed development; focus is on edible quality. |

| Edibility | Produce may not yet be ready for immediate consumption; ripening may occur postharvest. | Produce is suitable for consumption or can reach optimal quality with minimal postharvest ripening. |

| Determinants | Internal plant physiology, biochemical composition, and growth completion. | Market demand, transport distance, storage conditions, and consumer preferences. |

| Examples | Bananas harvested at physiological maturity ripen properly after harvest. Mango reaches physiological maturity when pulp is fully developed but firm. | Tomato harvested at breaker stage for local markets and at mature-green stage for distant markets. Citrus fruits are harvested when peel color and TSS:acid ratio match consumer preferences. |

| Purpose | Ensures seed viability and optimal postharvest ripening potential. | Ensures marketability, quality, and economic return. |

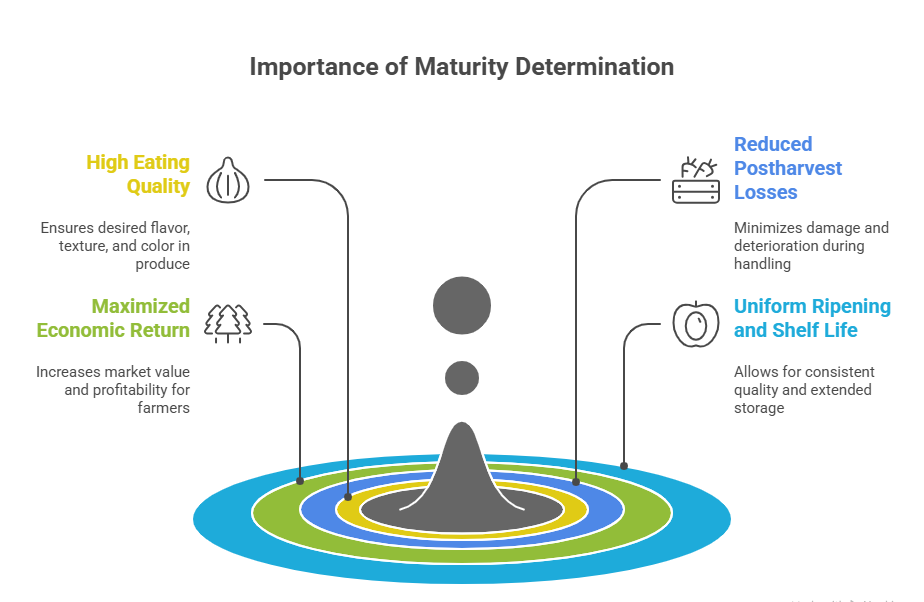

Importance of Correct Maturity Determination

I. Ensures High Eating Quality and Appearance

Determining the correct maturity of horticultural produce is essential for achieving optimum eating quality. Fruits and vegetables harvested at the appropriate stage of maturity develop the desired flavor, sweetness, texture, and color. Properly matured produce not only satisfies consumer expectations but also enhances the visual appeal, which is a critical factor influencing market demand and consumer preference.

II. Reduces Postharvest Losses During Transport and Storage

Correct maturity at harvest minimizes damage and deterioration during handling, transport, and storage. Immature produce is often more prone to shriveling, poor ripening, or susceptibility to diseases, while overmature produce can soften excessively or decay quickly. By harvesting at the right stage, farmers can significantly reduce postharvest losses, ensuring that a higher proportion of the produce reaches consumers in good condition.

III. Maximizes Economic Return for Farmers

Harvesting produce at the correct maturity directly affects the market value and economic return for farmers. High-quality produce commands better prices in both local and international markets. Additionally, reducing losses during storage and transport means that more of the harvest is saleable, thereby increasing profitability and improving the overall sustainability of agricultural operations.

IV. Facilitates Uniform Ripening and Longer Shelf Life

Proper maturity determination allows for more uniform ripening, which is particularly important for fruits that continue to ripen after harvest. Uniform ripening ensures consistent quality and appearance, making the produce more attractive to buyers and reducing sorting or grading efforts. Furthermore, harvesting at the correct stage can extend the shelf life of the produce, allowing for better inventory management and reducing waste at the consumer level.

Maturity Indices

Maturity indices are specific, measurable parameters that help determine whether a crop has reached the appropriate stage for harvest, ensuring optimal quality, marketability, and postharvest performance.

These indices can be physical, such as size, weight, firmness, or color; chemical, including sugar content, acidity, total soluble solids, or starch levels; physiological, such as seed development, respiration rate, or chlorophyll degradation; and visual, including external appearance, color changes, or surface texture.

By assessing one or a combination of these parameters, farmers and postharvest managers can accurately decide the right time to harvest, thereby improving eating quality, extending shelf life, reducing postharvest losses, and maximizing economic returns.

I. Physical Indices

| Parameter | Example |

| Size and shape | Mango, apple, tomato reach typical variety-specific size |

| Weight and volume | Potato, onion, cabbage |

| Firmness or texture | Penetrometer used for apple, mango |

| Color | Peel color changes in banana, citrus, tomato |

| Surface gloss | Loss of bloom in grapes indicates ripeness |

II. Chemical Indices

| Parameter | Description | Example |

| TSS (Total Soluble Solids) | Measured in °Brix using refractometer | Mango: 15–20°Brix, Tomato: 5–7°Brix |

| Titratable Acidity (TA) | Decreases with ripening | Citrus, Pineapple |

| TSS:Acid Ratio | Key flavor indicator | Citrus: 12:1 ideal |

| Starch to Sugar Conversion | Iodine test for apples, banana | |

| Chlorophyll Degradation | Measured by colorimeter or visually |

III. Physiological Indices

Respiration Rate

Respiration rate is a key physiological index used to assess the maturity of fruits. In most fruits, the respiration rate decreases significantly once the produce reaches physiological maturity. This decline indicates that fruit has completed most of its growth and energy-consuming metabolic processes. Monitoring respiration helps determine the optimal harvest time and predict postharvest behavior, such as ripening speed and shelf life.

Ethylene Evolution

Ethylene is a plant hormone that regulates ripening in climacteric fruits. The evolution of ethylene increases sharply at the onset of ripening, making it an important physiological marker for harvest timing. Measuring ethylene production allows farmers and postharvest managers to anticipate the ripening process and plan harvest, storage, and marketing strategies effectively.

Days from Flowering or Fruit Set

Another important physiological index is the number of days elapsed from flowering or fruit set to harvest. This parameter is crop-specific and provides a practical guideline for determining maturity. For example, bananas are typically harvested 110–130 days after flowering, depending on the variety and local growing conditions. Using flowering or fruit set as a reference helps ensure that the produce reaches both physiological and commercial maturity.

IV. Visual Indices

- Skin or pulp color change (green to yellow/red).

- Leaf drying in onion and garlic.

- Full slip in muskmelon (fruit detaches easily from stalk).

- Hollow sound in watermelon when tapped.

V. Maturity Indices of Some Major Crops

| Crop | Maturity Indicators |

| Mango | Color change from green to yellow, specific gravity 1.0, TSS 15–20°Brix |

| Banana | Ridges on peel flatten, brittleness of floral ends |

| Tomato | Color change from green to light red (breaker stage) |

| Citrus | TSS:Acid ratio ≥ 12:1 |

| Apple | Background color turns light green/yellow, starch test |

| Onion | Tops fall over and necks dry |

| Potato | Skin hardens, vines die back |

| Cabbage | Compact head formation |

| Cut Flowers | Bud opening stage specific to species (Rose: tight bud; Carnation: paint-brush stage) |

Harvesting Methods

I. Manual Harvesting

Manual harvesting is the most widely practiced method of harvesting horticultural crops, particularly in developing countries where mechanized harvesting technologies are limited. This method involves the use of simple tools such as knives, scissors, or sickles, or even direct hand-picking of fruits, vegetables, and other produce.

The primary advantage of manual harvesting lies in its selectivity, allowing workers to pick only fully matured or marketable produce while leaving immature items to develop further. Additionally, it is a low-cost method that requires minimal investment in machinery, making it accessible to smallholder farmers.

Despite these advantages, manual harvesting has notable limitations. It is labor-intensive and time-consuming, requiring a large workforce to harvest significant quantities of produce efficiently. Moreover, the process is prone to inconsistencies due to variations in worker skill and experience.

Improper handling during manual harvesting can lead to bruising, cuts, or other mechanical damage, which negatively affects the quality, shelf life, and market value of the produce. Consequently, while manual harvesting remains important in many regions, it demands skilled labor and careful handling to optimize postharvest quality and minimize losses.

II. Mechanical Harvesting

Mechanical harvesting refers to the use of specialized machinery to harvest crops efficiently, particularly in large-scale agricultural operations. This method involves equipment such as shakers, cutters, conveyors, and harvesters that can perform the collection of produce rapidly and with minimal manual labor. Mechanical harvesting is widely applied to crops like potato, onion, tomato, and other field-grown or bulk commodities, where labor-intensive methods may be inefficient or impractical due to the scale of production.

The primary advantage of mechanical harvesting is its speed and efficiency, which allows for the timely collection of large quantities of produce. By reducing reliance on human labor, mechanical harvesting can significantly lower production costs in commercial operations and improve overall operational productivity.

However, this method also has notable disadvantages. Mechanical harvesting is generally less selective than manual picking and can cause more physical damage to the produce, including bruising, cuts, or broken stems, which may reduce marketability and shelf life. Additionally, it requires crops to have uniform maturity; unevenly matured produce may be missed or harvested prematurely, affecting overall quality. Therefore, while mechanical harvesting offers substantial benefits in large-scale agriculture, careful management and appropriate machinery selection are essential to minimize postharvest losses and maintain product quality.

III. Time of Harvest

The timing of harvest is a critical factor in maintaining the quality, shelf life, and marketability of horticultural produce. Harvesting is ideally conducted during the cool periods of the day, such as early morning or late afternoon, when temperatures are lower and the produce has minimal field heat. Cooler temperatures at these times reduce water loss, wilting, and respiration rates, thereby preserving freshness and extending shelf life during transport and storage.

Harvesting during rainy conditions or under extreme sunlight should be avoided. Rain or high humidity can increase the risk of microbial infections and disease incidence, while intense sunlight and heat can cause stress, wilting, or sunscald in fruits and vegetables. These conditions can compromise both the visual appeal and internal quality of the produce.

For specialty crops such as cut flowers, harvesting is typically performed at the bud stage in the early morning. Flowers harvested at this stage have a longer vase life and better postharvest performance, as they have not yet fully opened, reducing damage during handling and transport. Proper timing of harvest, tailored to the specific requirements of each crop, is therefore essential for optimizing both product quality and economic returns for growers.

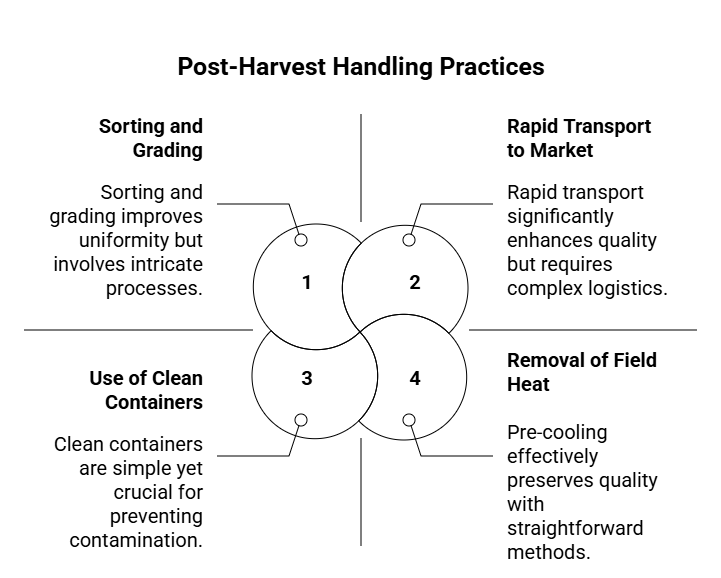

Post-Harvest Handling After Harvest

Proper post-harvest handling is essential for maintaining the quality, safety, and market value of horticultural produce. Immediately after harvest, several critical steps should be undertaken to reduce physiological stress, minimize losses, and prolong shelf life.

I. Removal of Field Heat through Pre-Cooling

Fruits and vegetables are typically harvested with a high field heat, which accelerates respiration and water loss. Pre-cooling is the process of rapidly lowering the temperature of freshly harvested produce to slow down metabolic activity. Methods such as forced-air cooling, hydrocooling, or vacuum cooling are commonly employed. Efficient pre-cooling helps reduce wilting, spoilage, and deterioration, ensuring that the produce remains fresh during transport and storage.

II. Sorting and Grading

Sorting and grading involve categorizing the harvested produce based on attributes such as size, color, and quality. This step not only enhances the visual appeal of the produce but also ensures uniformity for packaging and marketing. Sorting helps identify damaged, diseased, or substandard produce, which can be removed or processed separately, thereby reducing potential postharvest losses and maintaining overall quality standards.

III. Use of Clean Containers and Gentle Handling

Handling harvested produce carefully and using clean, sanitized containers is crucial to prevent mechanical damage, bruising, and contamination. Rough handling or use of dirty containers can lead to physical injury, microbial infection, and accelerated spoilage. Gentle handling preserves the structural integrity of the produce, maintaining its firmness, appearance, and marketability

IV. Rapid Transport to Market or Storage

Finally, harvested produce should be transported quickly to either the market or proper storage facilities. Delays in transportation can lead to moisture loss, microbial growth, and deterioration of quality. For perishable crops, ensuring a swift and efficient supply chain is essential to deliver fresh produce to consumers and maximize economic returns for farmers.

Overall, implementing these post-harvest handling practices immediately after harvest is fundamental for reducing losses, maintaining nutritional and sensory quality, and ensuring the produce reaches the market in optimal condition.

Practical Link

| Theory Concept | Related Practical Activity |

| Maturity indices | Maturity judgment and harvesting of fruits/vegetables |

| TSS and acidity | Determination of TSS and Titratable Acidity |

| Quality assessment | Organoleptic evaluation and hedonic rating |

Summary

- Maturity determination ensures optimal quality, shelf life, and consumer acceptance.

- Key indices include size, color, firmness, TSS, acidity, and days after flowering.

- Harvesting at physiological maturity for storage or commercial maturity for immediate sale is ideal.

- Proper timing and technique prevent mechanical damage and postharvest losses.

Frequently asked questions in Competitive Exams

- Define physiological and commercial maturity. Give examples for each.

- Describe the different maturity indices used for judging harvest maturity in fruits.

- Explain the importance of correct harvesting time in postharvest management.

- Discuss the physical and chemical parameters used to determine maturity.

- Write maturity indices for mango, banana, citrus, tomato, and onion.

- Explain the principle and use of a hand refractometer and penetrometer.

- Discuss the difference between manual and mechanical harvesting methods.

- Describe harvesting methods and precautions for cut flowers.

- Explain the relationship between maturity stage and storage life of horticultural crops.

- Describe postharvest operations immediately after harvest to maintain quality.

MCQs (Repeatedly Asked in Competitive examinations)

1. Physiological maturity refers to:

✅ a) Completion of natural growth and development

b) Achieving marketable color

c) Attaining eating quality

d) Starch conversion to sugar

2. Commercial maturity is determined mainly by:

✅ a) Market demand and quality preference

b) Seed viability

c) Leaf senescence

d) Flowering duration

3. Full slip in muskmelon indicates:

✅ a) Proper maturity for harvest

b) Disease infection

c) Nutrient deficiency

d) Overmaturity

4. The ratio of TSS to acidity in citrus is an important:

✅ a) Maturity index

b) Soil test parameter

c) Fertility measure

d) Ripening retardant

5. Specific gravity 1.0 in mango indicates:

✅ a) Maturity

b) Immaturity

c) Overripeness

d) Disease infection

6. Which instrument is used to measure TSS?

✅ a) Hand refractometer

b) Colorimeter

c) Penetrometer

d) Hygrometer

7. Iodine test in apple is used to estimate:

✅ a) Starch degradation

b) Sugar accumulation

c) Acidity

d) Vitamin C

8. Which of the following is a visual maturity index for banana?

✅ a) Flattening of ridges on peel

b) TSS:Acid ratio

c) Penetrometer reading

d) Chlorophyll content

9. Onion bulbs are ready for harvest when:

✅ a) Tops fall over and necks dry

b) TSS is maximum

c) Leaves are green

d) Bulbs are small

10. Watermelon maturity can be judged by:

✅ a) Hollow sound on tapping

b) Yellow pulp color

c) Vine senescence

d) Fruit firmness

11. Tomato for distant transport is harvested at:

✅ a) Mature green stage

b) Breaker stage

c) Pink stage

d) Fully red stage

12. The TSS of ripe mango usually ranges between:

a) 5–10°Brix

✅ b) 15–20°Brix

c) 25–30°Brix

d) 10–12°Brix

13. The device used to measure fruit firmness is:

✅ a) Penetrometer

b) Psychrometer

c) Densiometer

d) Hygrometer

14. Which of the following is a physiological maturity index for banana?

✅ a) Days after flowering (110–130 days)

b) Peel color

c) Taste

d) Sweetness

15. Which color change indicates maturity in tomato?

✅ a) Green to light red (breaker stage)

b) Red to yellow

c) Yellow to green

d) Purple to white

16. Morning harvest is preferred because:

✅ a) Temperature is lower, less field heat

b) Sugar content is high

c) Photosynthesis is active

d) Plants are turgid

17. Which factor is not an indicator of maturity?

a) Size

b) Color

✅ c) Soil moisture

d) Firmness

18. Commercial maturity of citrus is best judged by:

✅ a) TSS:acid ratio

b) Firmness

c) Fruit weight

d) Days after flowering

19. Harvesting fruits too early generally leads to:

✅ a) Poor flavor and shriveling

b) Better color

c) Longer shelf life

d) Higher sugar content

20. Which tool is commonly used for manual fruit harvesting?

✅ a) Secateur or picking pole

b) Hoe

c) Spade

d) Harrow

References:

- Gautam, D.M. & Bhattarai, D.R. (2012). Postharvest Horticulture.

- Kays, S.J. (1998). Postharvest Physiology of Perishable Plant Products.

- Bautista, O.K. (1990). Postharvest Technology for Southeast Asian Perishable Crops.