Tobacco Farming

Tobacco farming profit per acre demonstrates significant economic potential, as evident from a profit analysis showing a total income of NRs 100,000 against an investment of NRs 48,000. This yields a net profit of NRs 52,000, reflecting a profit margin of 52% and a benefit-cost ratio of 2.08, indicating that for every rupee invested, the return is more than double, making tobacco cultivation a lucrative agricultural venture.

Land Preparation

Land preparation for tobacco farming aims to create a fine, weed-free, well-aerated seedbed that is ideal for germination and early seedling growth, followed by preparing the main field for transplanting.

This process involves two key stages: preparing the nursery beds and preparing the main field. Specifically, nursery beds are established in a sunny, well-drained location where the soil is finely pulverized, mixed with well-decomposed organic manure (such as compost or FYM), and often sterilized (using steam or restricted chemicals like methyl bromide) to eliminate pathogens, pests, and weed seeds; these prepared beds are then formed into raised structures approximately 1 meter wide and 10-15 cm high and smoothed.

Meanwhile, the main field undergoes deep plowing (20-25 cm) after removing the previous crop to break up compaction, improve aeration and drainage, and incorporate residues or organic matter; subsequent harrowing and leveling then create a fine tilth, and ridges or furrows are typically formed based on the intended planting method.

Soil Type

Tobacco thrives best in well-drained, fertile sandy loam to loam soils, with drainage being critical as poorly drained soils cause waterlogging, promote diseases like black shank, and hinder root development.

While moderate to high fertility is required, the soil must be balanced, as excessive nitrogen leads to rank growth and poor curing; sandy loams are advantageous for warming quickly in spring, aiding early growth, while loams better retain moisture and nutrients, but heavy clay soils are generally avoided due to their poor drainage and workability.

Maintaining a slightly acidic to neutral pH (optimally 5.8 to 6.5) is essential, necessitating soil testing to guide necessary adjustments of lime or fertilizer.

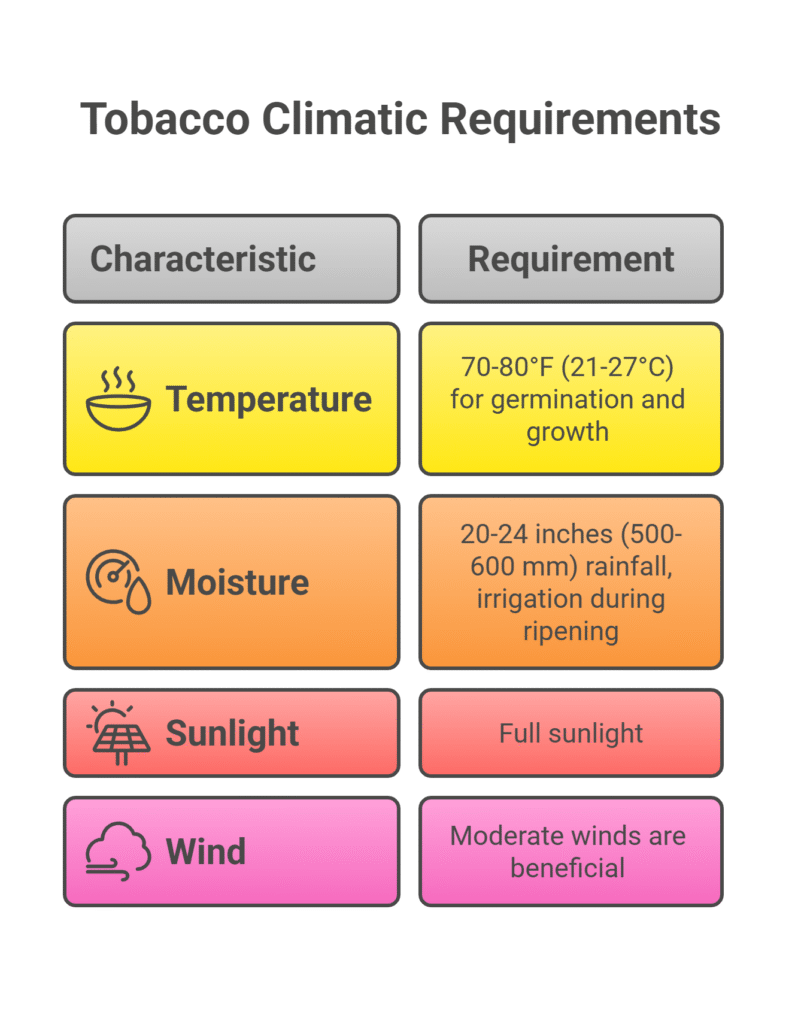

Climatic Requirements

Tobacco, a warm-season crop, thrives in frost-free conditions lasting 90-120 days and has precise climatic requirements. Germination is most effective at temperatures of 70-80°F (21-27°C), which are also ideal for growth, although temperatures below 55°F (13°C) slow development, and extreme heat above 95°F (35°C) can cause damage.

Steady moisture is vital, particularly during the rapid growth phase 6-8 weeks after transplanting, with a well-distributed rainfall of 20-24 inches (500-600 mm) being ideal, followed by drier conditions for ripening and harvesting, often supported by irrigation. Full sunlight is necessary for optimal growth and leaf quality, while moderate winds can strengthen the stalks.

However, strong winds pose risks, including lodging and leaf damage from sandblasting or tearing. Additionally, curing processes—such as air, flue, fire, or sun curing—require specific temperature and humidity conditions to ensure quality post-harvest.

Major Cultivars

| Cultivar Type | Color | Sugar/Nicotine Content | Curing Method | Primary Usage | Examples |

| Flue-Cured (Virginia) | Bright yellow to orange | High sugar, medium nicotine | Flue-Cured | A major component of cigarettes | K326, NC71, PVH 2110 |

| Burley | Light to dark brown | Low sugar, high nicotine | Air-Cured | Cigarettes, some smokeless tobacco | TN 90, KY 14×8 |

| Oriental (Turkish/Aromatic) | Small leaves | High aroma, low nicotine | Sun-Cured | Flavoring in blends | Basma, Samsun, Xanthi |

| Dark Air-Cured & Fire-Cured | – | – | Air-Cured / Fire-Cured | Cigars, chewing tobacco, snuff, pipe blends | Havana, CT Broadleaf (Air); Perique (Fire) |

| Cigar Wrapper/Binder | – | – | Grown under shade | Cigar wrappers/binders (large, thin, elastic leaves) | Connecticut Shade, Sumatra |

Seed rate

The recommended tobacco seed rate for nursery production sufficient to plant one acre is 1.4 kg.

Nursery Management

Successful tobacco seedling production requires well-managed nurseries or seedbeds to grow seedlings to transplanting size. The site should have sandy or sandy loam soil with excellent drainage, preferably elevated, and should be rotated annually to reduce pests, diseases, and varietal contamination.

If reusing a site, sterilization through rabbing—burning slow-burning waste like tobacco stalks or paddy husks—is essential before sowing. Proper site preparation involves thorough bed preparation, adequate manuring, reliable watering facilities, and timely pest and disease control to ensure healthy seedling growth.

Planting

a). Planting Season

The optimum time for sowing tobacco nurseries and transplanting the seedlings varies depending on the location and the specific types and varieties grown, even within the same area; although generally, nurseries are raised between April and May, with transplanting completed by October.

b) Spacing

Spacing requirements differ depending on the species; the appropriate distances between rows and between individual plants are outlined below.

| Cultivar Type | Within-Row Spacing | Between-Row Spacing | Plant Density (per acre) | Remarks |

| Flue-Cured (Virginia) | 60 cm | 120 cm | 5620 | Narrower spacing for higher yield |

| Burley | 55 cm | 110 cm | 6689 | Tolerates moderately dense planting |

| Oriental (Turkish/Aromatic) | 30 cm | 70 cm | 19271 | Small plants allow high density |

| Dark Air-Cured & Fire-Cured | 60 cm | 120 cm | 5620 | Wider spacing for large-leaf types |

| Cigar Wrapper/Binder | 70 cm | 150 cm | 3854 | Maximum spacing for leaf quality |

c) Planting Method

Seedlings are ready for field planting upon reaching 6 inches (15 cm) in height with 4–6 true leaves, typically after 6–8 weeks. Before transplanting, growers ensure soil temperatures exceed 65°F (18°C) to support healthy root development. Seedlings are pulled as bare-root plants or popped from trays and then transplanted into moist soil in prepared furrows or ridges, often using mechanical transplanters, followed by immediate watering. For the initial weeks post-transplant, seedbeds are covered to shield the vulnerable young plants from adverse weather.

Irrigation

Waterlogging for over 48 hours can cause severe root damage or plant death, while inconsistent watering reduces leaf quality and lowers market value. Oversaturation leads to nutrient leaching and promotes diseases, and chronic water stress results in stunted growth and premature flowering. Drip irrigation offers an optimal solution by delivering water precisely to the root zone, minimizing waste and runoff, preventing leaf wetting to reduce disease risk, and is increasingly adopted in commercial operations.

| Growth Stage | Water Requirements | Purpose / Strategy | Risks of Poor Management |

| Germination | Light, frequent watering | Establish seedlings; controlled pre-transplant deficit enhances drought resilience | Inconsistent moisture reduces germination success |

| Active Growth (Peak: 50–70 days post-transplant) | Consistent, moderate irrigation | Maximize yield potential and leaf development; prevent water stress | Stress causes irreversible yield/quality loss |

| Maturation | Reduced application: mild stress induced | Limit new leaf growth; direct plant resources to existing leaves | Excess water dilutes flavor compounds, delays ripening |

Fertilizer and Manure

Tobacco is a nutrient-hungry plant with distinct seasonal requirements: early growth benefits from nitrogen fertilization to support leaf development, while later stages demand potassium to improve chemical content and burn characteristics of leaves, typically applied via broadcast spreading (pre-plant) and band placement (side-dress).

However, its cultivation requires extensive chemical inputs and causes more severe soil macronutrient depletion than most cash crops – a problem exacerbated by practices like topping and de-suckering, which increase nicotine levels but further strain soil resources.

Topping

Topping is the practice of removing the terminal bud of a tobacco plant, often along with some of the upper leaves, either just before or shortly after the flower head emerges. This process redirects the plant’s energy from flower production to the development of leaves, enhancing their size, quality, and nicotine content. Topping is a critical cultural practice in tobacco farming, as it improves leaf yield and quality, which are essential for better market value.

Desuckering or suckering

After topping, axillary buds grow into shoots called suckers, which are removed in a process known as desuckering or suckering. Topping and desuckering aim to redirect the plant’s energy and nutrients from flower and sucker growth to the leaves, enhancing their size, yield, and quality. This practice is standard for most tobacco types, except wrapper tobacco, where maintaining texture is a priority.

Weed Control

Weed problems in tobacco are acute in both seedbeds and transplanted fields, with Orobanche emerging as a predominant parasitic weed; effective weed control is critical as weeds aggressively compete for nutrients, water, and light, significantly reducing crop yield and quality while harboring pests and diseases. Control methods include:

| Control Method | Details | ||

| Cultural Practices | Crop rotation, use of clean seed/transplants, and optimal spacing to promote canopy closure. | ||

| Mechanical Cultivation | Shallow hoeing or ridging during the early season to avoid root damage | ||

| Chemical Herbicides | Apply herbicides such as Pendimethalin at 1 ml/L as pre-emergence treatments, and Carfentrazone or Clethodim at 1 ml/L as post-emergence treatments. Adhering strictly to label-recommended rates is crucial. | ||

| Manual Weeding | Labor-intensive methods, such as hand hoeing, are primarily used in organic systems. | ||

Pest and Disease

Common Pests

a) Tobacco hornworms

Tobacco hornworms are destructive pests of tobacco plants, feeding on leaves and causing significant damage. Effective management includes regular monitoring, handpicking in small plantings, promoting natural predators like parasitic wasps, timely application of insecticides when necessary, and removing crop residues to prevent overwintering and reduce future infestations.

b) Aphids

Aphids are significant tobacco sap-sucking parasites that infest the undersides of leaves and delicate shoots, especially the green peach aphid (Myzus persicae). By depleting plant nutrients and releasing sticky honeydew, they directly harm plants by encouraging the formation of sooty mold, which lowers photosynthesis and leaf marketability. Importantly, harmful plant viruses like Potato Virus Y and Tobacco Etch Virus are also spread by aphids. Scouting, the use of insecticides (such as imidacloprid), and biological agents like lady beetles or parasitoid wasps (Aphidius spp.) are all part of the control strategy.

c) Cutworms

Cutworms are soil-dwelling pests that damage tobacco seedlings by cutting stems at or near ground level. Effective control measures include monitoring and removing larvae, maintaining clean fields to reduce habitats, using barriers around plants, and applying appropriate insecticides if infestations persist. Proper land preparation and crop residue management also help minimize cutworm populations.

Common Diseases

a). Damping-off

Damping-off, caused by soil-borne fungi like Pythium, Rhizoctonia, and Fusarium, is a devastating disease affecting tobacco seedlings in seedbeds, thriving in cool, waterlogged conditions. It manifests as pre-emergence rot (seeds failing to sprout) or post-emergence collapse (seedlings wilting at the soil line with water-soaked, pinched stems). Prevention relies on strict sanitation—using sterilized media, well-draining seedbeds, reduced watering, and fungicide-treated seeds—as infected seedlings rarely survive.

b). Black Shank

Black Shank, caused by the aggressive soil-borne oomycete Phytophthora nicotianae, is one of tobacco’s most destructive diseases, capable of causing near-total crop loss in infected fields. It manifests as sudden wilting and yellowing of leaves, blackened stem lesions at the soil line, and rotted, blackened roots, often leading to plant collapse.

The pathogen thrives in warm, wet soils and spreads rapidly via water, contaminated equipment, or infected transplants. Control relies integrated strategies: planting resistant cultivars (e.g., NC 1023, K 346), strict field sanitation, crop rotation (4+ years away from solanaceous crops), raised beds for drainage, and targeted fungicides like mefenoxam—though pathogen resistance remains a growing challenge.

c). Blue Mold

Blue mold, primarily caused by fungi of the Penicillium genus (recognizable by its blue or blue-green powdery spores), is a common agent of food spoilage, particularly affecting fruits (like citrus and pome fruits), vegetables, bread, grains, nuts, and dairy products; while some species produce harmful mycotoxins (e.g., patulin, ochratoxin A) posing health risks, notably to immunocompromised individuals, other Penicillium strains are critically beneficial as the source of the antibiotic penicillin and are intentionally used in the production of certain blue-veined cheeses (e.g., Roquefort, Gorgonzola, Stilton).

d) Brown Spot

Brown Spot is a common tobacco disease that lowers leaf quality and output. It is brought on by the fungus Alternaria alternata. It manifests as tiny, round, brown lesions with concentric rings that frequently swell and clump together in moist environments.

Dense plantings, poorly drained soils, and stressed or elderly plants are all favorable environments for the disease. Management entails removing infected material, applying fungicides on time, maintaining plant health through balanced fertilization to lower susceptibility, and ensuring correct field drainage and plant spacing.

e) Tobacco Mosaic Virus

The highly contagious tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) damages tobacco and other crops by producing distortion, slowed growth, and mosaic-like leaf mottling, all of which lower yield and quality. Human contact, contaminated plant material, and instruments are the main ways that the virus spreads. Planting resistant cultivars, maintaining stringent hygiene, avoiding handling wet plants, eliminating sick plants, and sterilizing equipment are all part of management to reduce transmission.

Harvesting

Tobacco typically requires 90 to 130 days from transplanting to harvesting, depending on factors such as the variety, environmental conditions, and management practices. Harvesting methods and signs of maturity vary depending on the type of tobacco being cultivated. Generally, there are two primary harvesting techniques: the priming method and the stalk-cutting method.

| Harvesting Method | Tobacco Types Applicable | Procedure | Timing / Key Steps | Additional Notes |

| Priming | Flue-Cured, Oriental | In tobacco cultivation, the lower leaves typically mature first, followed sequentially by the upper leaves in an ascending order. Harvesting involves removing a few leaves at a time as they reach maturity, a practice known as priming. This method is commonly used for harvesting cigarettes and wrapper tobaccos. | 2-5+ passes at 1–2-week intervals as leaves ripen from bottom up | Requires skilled labor to select ripe leaves (color change, slight drooping, brittle tip) |

| Stalk-Cutting | Burley, Dark Air-Cured, Fire-Cured | In this method, plants are cut near the base using a sickle and typically left in the field overnight to wilt. Further handling depends on the chosen curing method. Harvesting is timed to ensure the maximum number of leaves have reached full maturity. | When most leaves are mature (often at flowering start/shortly after) | Sometimes topped (flower head removed) 1-2 weeks before cutting |

Post Harvesting

Curing

Curing is a gradual process that induces a form of starvation in tobacco leaves to produce dried leaves with desirable physical and chemical qualities, achieved through careful control of ventilation, temperature, and humidity. Although the leaf is biologically dead at the end of curing, some active enzymes may still be present.

The fresh leaf’s components can be divided into three groups that change differently during curing: the static, dynamic, and nitrogen groups. The static group, which includes crude fiber, cellulose, hemicellulose, pectins, and tannins, remains relatively stable.

The nitrogen group, consisting of proteins, soluble nitrogen compounds like ammonia, nitrates, amides, and alkaloids, undergo some changes. The most significant transformations occur in the dynamic group, which contain sugars, starches, and organic acids, and these changes are crucial for the final leaf quality.

Cost of Investment Per-Acre Tobacco Farming

| S.N. | Category | Cost (NRs) |

| 1 | Land Preparation (plowing) | 10,000 |

| 2 | Seed | 2,000 |

| 3 | Nursery Management & Transplanting | 5,000 |

| 4 | Fertilizers & Manure | 7,000 |

| 5 | Irrigation | 8,000 |

| 6 | Weed Control | 3,000 |

| 7 | Pest & Disease Control | 3,000 |

| 8 | Harvesting | 5,000 |

| 9 | Post-Harvest (Curing) | 2,000 |

| 10 | Miscellaneous Costs | 3,000 |

| Total Cost | 48,000 |

Income from per-acre tobacco farming

| Particulars | Yield (kg/acre) | Market Price (NRs/kg) | Income (NRs) |

| Tobacco | 1,000 | 100 | 100,000 |

Analysis of Tobacco Farming Profit Per Acre

The profit analysis reveals a total income of NRs 100,000 against a total investment of NRs 48,000, resulting in a net profit of NRs 52,000. This equates to a profit margin of 52%, calculated as (Profit ÷ Income) × 100, and a benefit-cost ratio of 2.08, indicating that for every rupee invested, the return is more than double the investment.

References

FAO. (2010). “Tobacco Production and Management.

USDA NRCS. (2020). “Tobacco Production Practices.