Fig Farming

Figs (Ficus carica), the highly nutritious, vitamin-rich fruits cultivated in subtropical and Mediterranean climates, have emerged as a lucrative agricultural venture with significant fig farming profit per acre potential. These fast-growing plants, consumed fresh, dried, or processed into value-added products like jams, are gaining global demand due to their health benefits and antioxidant properties. Modern smart farming techniques enhance their cultivation through optimized irrigation and resource management, though challenges like power outages and leaf rust require attention.

Fig trees, typically reaching 15–20 ft with delicate wood, produce versatile fruits in vibrant colors that transition from latex-filled to sweet upon ripening. Their resilience to diverse climates—tolerating temperatures as low as 10°C without winter chilling needs—makes them ideal for tropical to subtropical regions, including Southeast Asia.

For farmers evaluating fig farming profit per acre, two systems stand out: low-density (202 plants/acre) with NPR 18.75M net profit over 20 years, and high-density (450 plants/acre) yielding NPR 33.55M—a 79% increase—despite higher initial costs. This combination of nutritional value, climatic adaptability, and proven profitability positions figs as a strategic crop for sustainable and commercial agriculture.

Land Preparation

Proper land preparation for fig cultivation begins with clearing the field of weeds, stones and debris, followed by deep plowing (30-45 cm) to improve soil aeration and facilitate root penetration. The land should then be leveled to ensure uniform water distribution, while incorporating organic matter such as compost or farmyard manure to enhance soil fertility and provide essential nutrients for optimal fig tree growth.

Soil Type

As long as there is sufficient soil depth and appropriate drainage, figs can be grown in a variety of soil types, including light sand, rich loams, clay, and limestone. For best results, well-drained sandy-loam or loamy soils with high levels of organic matter are ideal. Saline or wet environments are totally inappropriate for growing figs, and heavy clay soils should be avoided as they hold too much moisture and cause root rot. The best soil pH range for fig production is between 6.0 and 6.5, which encourages greater root development and phosphate absorption. Highly acidic soils are not good for healthy plant growth, whereas moderately fertile, well-drained soils with a high organic content are optimal.

Climatic Requirements

Warm areas with optimal temperatures between 20°C and 35°C are good for fig growth. They need 600–1000 mm of rainfall each year, although they should not be overly wet during fruiting to avoid fruit splitting. Since high humidity can encourage fungal diseases that could jeopardize plant health and fruit quality, these sun-loving plants require full sunlight exposure for at least eight hours every day in order to produce at their best. Warm temperatures, moderate rainfall, lots of sunshine, and balanced humidity make for the ideal growing conditions for fruitful fig production.

Major Cultivars

Popular fig varieties include:

a). Black Mission

Popular for its rich, sweet flavor with undertones of berry, the Black Mission fig is distinguished by its dark purple to black skin. It is perfect for eating fresh, drying, or preserving because of its incredibly juicy and soft pink-amber flesh. Because it bears fruit twice a year (in early summer and late fall), this extremely productive cultivar is valued for its extended harvest season and thrives in warm areas. Both commercial farmers and home gardeners love it for its versatility and drought tolerance.

b). Kadota

The Kadota fig is a classic variety recognized for its smooth greenish-yellow skin and mild, less sweet flavor with subtle honey notes. Its amber-colored flesh is firm and nearly seedless, making it particularly ideal for canning, drying, and fresh consumption. Unlike sweeter varieties, Kadota maintains its shape well when processed, earning it the nickname “the canning fig.” This vigorous, heat-tolerant cultivar produces reliable crops in warm climates and is valued for its extended shelf life and versatility in culinary uses, especially in preserves and baked goods.

c). Brown Turkey

The Brown Turkey fig is a hardy, cold-tolerant variety prized for its brownish-purple skin and sweet, mildly rich flavor with notes of honey. Its pink-amber flesh is juicy and moderately seedy, making it excellent for fresh eating, drying, or preserves. Particularly valued by growers in cooler climates, this resilient variety can withstand temperatures as low as 10°F (-12°C) when established, while still producing reliable, heavy crops. Its disease resistance and adaptability make it one of the most widely planted figs for both backyard gardens and commercial production, typically yielding two harvests per season in warmer regions.

d). Adriatic

The Adriatic fig is a prized variety known for its light green to yellowish skin and exceptionally sweet, honey-like flavor, making it one of the best figs for drying and fresh consumption. Its strawberry-red flesh is tender and nearly seedless, with a high sugar content that intensifies when dried – earning it the nickname “white fig” or “sugar fig.”

Traditionally grown in Mediterranean regions, this variety is particularly valued by commercial producers for fig bars, pastes, and premium dried figs due to its superior drying qualities and thin skin. While highly productive in warm climates, the Adriatic fig requires protection from extreme cold and maintains its popularity among home growers and commercial orchards for its balanced sweetness, versatility, and reliable yields.

e). Calimyrna

The Calimyrna fig is a premium variety distinguished by its large golden-yellow fruits and unique nutty flavor, often compared to almonds or walnuts, making it highly prized for both fresh consumption and drying. Unlike most common figs, this variety requires pollination by fig wasps (a process called caprification) to produce its full-sized fruits, limiting its cultivation to regions where these specific wasps are present.

Originally from Turkey (where it’s called “Sari Lop”), the Calimyrna develops a light green to golden skin when ripe, with luscious pink-amber flesh that becomes exceptionally sweet when dried. Primarily grown in California’s Central Valley, this fig is celebrated for its complex flavor profile, firm texture, and superior quality in dried form, though its cultivation demands more attention than self-pollinating varieties due to its specific pollination requirements.

Planting

Fig farming (Ficus carica) is increasingly being adopted in both traditional outdoor settings and controlled greenhouse environments, thanks to the crop’s strong positive response to agricultural techniques. While open-field cultivation struggles with issues such as pest infestations, disease outbreaks, rainfall-induced fruit spoilage, and inadequate farming practices that compromise output quality and quantity, greenhouse farming presents an effective alternative.

Protected cultivation demonstrates significant advantages, including dramatically increased productivity (potentially tenfold higher), continuous annual harvests, and reliable shelter from harsh climatic conditions. Research indicates that greenhouse-grown figs can achieve more than five harvest cycles annually, with the regulated conditions optimizing plant development, bloom formation, and fruit characteristics. This approach proves particularly valuable in tropical areas prone to intense precipitation and strong winds, delivering more consistent and higher-quality yields than conventional outdoor cultivation methods.

a). Planting Season

The optimal planting season for figs is during spring (February–March) or early monsoon (June–July) when temperatures are moderate, avoiding periods of extreme heat or frost that could stress young plants and hinder establishment. These seasons provide ideal conditions for root development and acclimatization, with spring plantings benefiting from warm growing seasons and monsoon plantings utilizing natural rainfall for initial irrigation, while careful timing ensures protection from temperature extremes that could compromise plant health and early growth.

b). Spacing

For traditional low-density fig cultivation, maintain 5 meters between rows and 4 meters between plants to allow ample space for canopy growth and airflow. High-density planting systems using dwarf varieties can adopt tighter 3m×3m spacing, significantly increasing plant numbers per acre while requiring more intensive management of pruning and irrigation to maintain plant health and productivity. The spacing choice depends on variety vigor, soil fertility, and desired management intensity, with closer spacing offering higher early yields but demanding greater long-term canopy control.

c). Pit Preparation

For proper pit preparation, dig 60 cm × 60 cm × 60 cm holes and enrich the excavated topsoil by thoroughly mixing in 10–15 kg of well-decomposed manure, 500g of Single Super Phosphate (SSP), along with beneficial microbial inoculants including 50g of Trichoderma viridae and 50g of composite biofertilizers containing nitrogen-fixing bacteria, phosphate-solubilizing bacteria (PSB), and potassium-mobilizing bacteria to create an optimal growth environment for fig saplings, ensuring proper nutrient availability and soil microbial activity from the establishment phase.

d). Planting Method

To plant fig saplings (whether tissue-cultured or cuttings), position them carefully in the center of the prepared pit, then fill the surrounding space with the enriched soil mixture while gently firming it around the roots to eliminate air pockets, and immediately water thoroughly to settle the soil and ensure proper root-to-soil contact for optimal establishment. This method promotes healthy root development and gives the young plants the best start in their new growing environment.

e). Number of Plants per Acre

The number of fig plants per acre varies significantly depending on the cultivation system, with traditional low-density planting accommodating approximately 202 plants/acre using standard spacing (5m×4m), while modern high-density systems utilizing dwarf varieties can support up to 450 plants/acre with tighter 3m×3m spacing – this intensive approach nearly doubles plant numbers while requiring specialized pruning and management techniques to maintain plant health and productivity in the constrained growing space.

Intercropping

Intercropping in fig orchards can be practiced during the initial 3–4 years by planting compatible short-statured crops like legumes (beans, peas), garlic, onions, or fast-growing vegetables between fig trees, which efficiently utilizes space while improving soil fertility through nitrogen fixation (in case of legumes) and weed suppression; however, tall crops that cast shade on young fig plants must be avoided as they compete for sunlight, and this practice should be discontinued once fig trees reach maturity (typically after 3–4 years) to prevent competition for nutrients and water as the fig canopy develops fully. This strategic intercropping system optimizes land use during establishment while prioritizing fig tree growth at maturity.

Irrigation

During the first three months, young fig seedlings need to be watered twice a week to guarantee appropriate establishment. In contrast, older trees, which are inherently drought-tolerant, need to be watered every 10 to 15 days during extended dry spells to maintain optimal fruit production. The most effective technique is drip irrigation, which minimizes waste and lowers the risk of fungus while supplying water straight to the root zone. Waterlogging, however, must be avoided at all costs since, especially in poorly drained soils, too much moisture encourages root rot and other soil-borne illnesses.

Fertilizer and Manure

The basal dose is applied only once during pit preparation, while annual fertilizer applications are applied into 3 equal split doses in March, July, and October for optimal nutrient uptake. Additionally, foliar sprays of micronutrients are particularly recommended during critical growth phases like flowering and fruit development to enhance yield quality and address any nutrient deficiencies.

| Application Type | Details | Quantity (Per Tree/Pit) |

| Basal Dose (At Planting) | Farm Yard Manure (FYM) + Single Super Phosphate (SSP) + Muriate of Potash (MOP) | 10–15 kg FYM + 500g SSP + 250g MOP |

| Annual Application | Year 1–2: Nitrogen (N), Phosphorus (P), Potassium (K) | 50–100g N (Urea) + 50g P + 50g K |

| Year 3+: Nitrogen (N), Phosphorus (P), Potassium (K) | 200–300g N + 100g P + 150g K | |

| Foliar Sprays | Micronutrients (Zinc, Magnesium, Boron) for fruit quality enhancement | As per deficiency symptoms |

Weed Control

Effective weed control in fig orchards combines mulching (using organic materials or plastic sheets) to suppress weed growth and conserve soil moisture, along with regular manual weeding during the first two critical years to prevent competition with young plants. While targeted herbicide applications (such as Glyphosate) may be used with extreme caution in mature orchards, they must be carefully applied to avoid any contact with the fig trees to prevent chemical damage, making integrated weed management crucial for healthy fig cultivation.

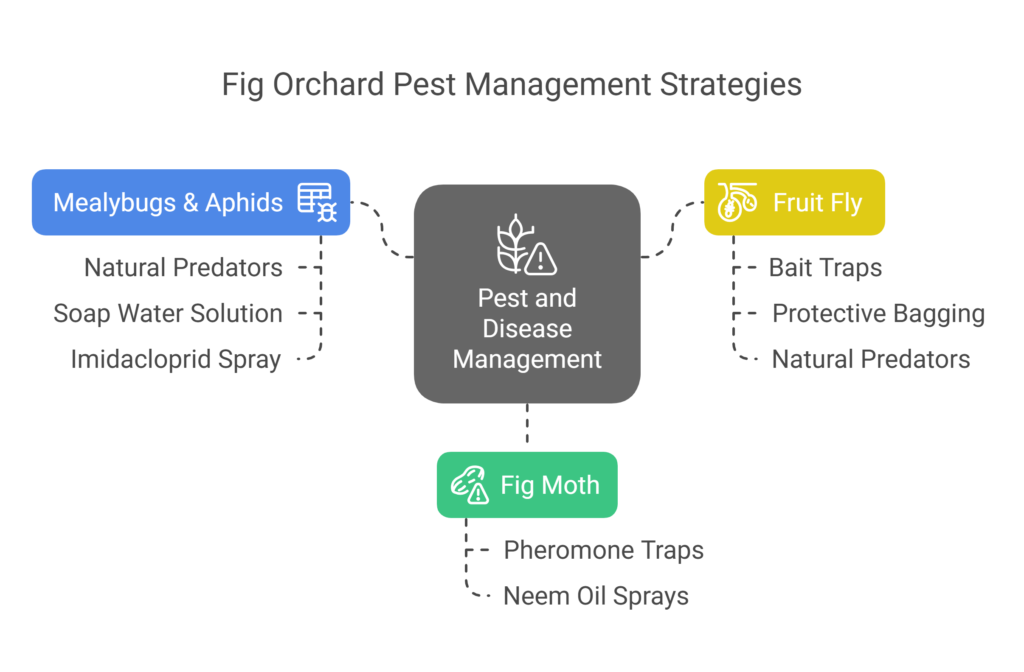

Pest and Disease Management

Common Pests

a). Fig Moth

The fig moth poses a significant threat as its larvae burrow into and damage ripening fruits but can be effectively managed through pheromone traps to disrupt mating and neem oil sprays as an organic control method to deter infestations while maintaining fruit quality.

b). Mealybugs & Aphids

Mealybugs primarily infest older, shaded fig orchards in heavy soils, feeding on roots, bark, leaves, and fruits while injecting toxic saliva that causes defoliation, fruit discoloration, splitting, and premature dropping. These pests congregate densely, secreting honeydew that promotes black sooty mold growth while triggering twig dieback and leaf loss. Fortunately, natural predators like R. fumida, Chrysoperla zastrowii silemi, and Cacoxenus perspicax help control infestations biologically.

Management

- Spray soap water solution.

- Spray imidacloprid 1ml/litre water.

c). Fruit Fly

Fruit flies cause severe damage to fig trees through three primary mechanisms: 1) egg-laying in fruits and tender plant tissues, 2) destructive larval feeding that leads to internal rotting and tissue breakdown, and 3) secondary infections from bacteria and fungi entering through larval tunnels. The most devastating impact comes from larval feeding, which distorts young fruits (causing callusing and premature dropping) and gives mature fruits a water-soaked appearance, while even light infestations reduce marketability through visible puncture wounds and decay. Natural predators like rove beetles, weaver ants, spiders, birds and bats help control populations, along with parasitoid wasps including Opius longicaudatus, O. vandenboschi, O. oophilus, and Bracon species that target fruit fly larvae.

Management

To control fruit fly infestations, bait traps containing attractants like methyl eugenol can effectively reduce adult populations, while protective bagging of individual fruits with breathable materials prevents egg-laying and larval damage, offering a dual approach that combines mass trapping with physical barriers for sustainable pest management.

Major Diseases

a). Fig Rust

Fig rust typically emerges in late summer, causing severe defoliation within weeks during intense outbreaks, which can stunt tree growth and reduce yields if recurring. Early-summer defoliation triggers vulnerable new growth prone to frost damage, while autumn leaf drop may induce premature dormancy, offering frost protection.

Initial symptoms appear as small yellow spots on leaf surfaces that expand into smooth reddish-brown lesions; the underside develops raised, blister-like rust pustules, with heavily infected leaves yellowing/browning at the edges before premature shedding. The fungus persists via teliospores in fallen leaves or soil, spreading through airborne uredospores, and thrives in warm, humid conditions (25.5–30.5°C with 86–92% relative humidity).

Management

- Spray copper-based fungicides (Copper oxychloride) 2-3 g/ liter of water.

b). Fig Mosaic

Fig mosaic manifests as yellow spots and mottling on leaves, with diffuse margins that gradually blend into healthy green tissue, appearing either uniformly or as irregular patches across the leaf surface, while mature lesions develop distinctive brown-red borders. The disease is primarily transmitted by microscopic fig mites (Aceria ficus) or through grafting infected plant material, making preventive measures and clean propagation practices essential for control.

c). Anthracnose

Anthracnose, a widespread fungal disease, can infect all parts of fig trees at any growth stage, with the most noticeable symptoms appearing on leaves and ripe fruits as small black, yellow, or brown spots that gradually expand and merge, eventually causing extensive damage. The disease also leads to stem and petiole cankers, severe defoliation, and root rot, while infected fruits develop sunken circular lesions that may produce pink spores. The fungus spreads through airborne and planting material-borne conidia, as well as infected plant debris, thriving under favorable conditions such as continuous rainfall, temperatures of 28–30°C, and high humidity.

Management

- Use Mancozeb or Carbendazim 2ml / liter of water.

- Effective control can be achieved by spraying aureofungin (40 ppm in soap solution) + copper sulfate (20 ppm).

Harvesting

Figs typically begin bearing fruit two years after planting, with ripeness indicated by a soft texture, slight drooping, and cultivar-specific color changes. Harvesting should be done carefully by hand to prevent bruising. Young trees (3–5 years) yield 5–10 kg per tree, while mature trees (6+ years) produce 20–50 kg per tree. For fresh market storage, maintain temperatures at 4–7°C, or sun-dry the figs for preservation.

Cost of Investment for Fig Farming Per Acre

| S.N. | Categories | Low Density (NPR) | High Density (NPR) |

| 1 | Land Preparation (Plowing, Leveling) | 40,000 | 60,000 |

| 2 | Fig Saplings | 60,000 | 135,000 |

| 3 | Fertilizers & Manure | 40,000 | 60,000 |

| 4 | Drip Irrigation Setup | 150,000 | 250,000 |

| 5 | Labor (Planting & Maintenance) | 40,000 | 60,000 |

| 6 | Pest & Disease Control | 30,000 | 40,000 |

| 7 | Miscellaneous (Equipment, Mulch, etc.) | 30,000 | 40,000 |

| Total Initial Cost | 390,000 | 645,000 |

Annual maintenance cost of Fig Farming Per Acre

The annual maintenance cost for fig farming starts from the second year onward, ranging between NPR 100,000–150,000 per acre for low-density planting (202 plants/acre) and NPR 120,000–180,000 per acre for high-density systems (450 plants/acre), where the slightly higher expenses reflect the increased labor and inputs required for intensive canopy management, irrigation, and fertilization in closely spaced orchards.

Income from Fig Farming Per Acre

| Year | Low-Density Yield (kg) | High-Density Yield (kg) | Price (NPR/kg) | Low-Density Income | High-Density Income |

| 2nd | 450 kg | 680 kg | 250 | 112,500 | 170,000 |

| 3rd | 1,000 kg | 2,000 kg | 250 | 250,000 | 500,000 |

| 4th | 2,500 kg | 4,000 kg | 250 | 625,000 | 1,000,000 |

| 5th | 4,500 kg | 6,500 kg | 250 | 1,125,000 | 1,625,000 |

| 6th–20th | 5,200 kg | 9,000 kg | 250 | 1,300,000/year | 2,250,000/year |

Analysis of Fig Farming Profit Per Acre

a). Low-Density Fig Farming (202 Plants/Acre)

Low-density fig farming (202 plants/acre) requires an initial investment of NPR 390,000, with annual maintenance costs of NPR 130,000 from year 2 onward. The operation generates no income in the first year, with profits beginning in year 2 (NPR 112,500) and gradually increasing to NPR 1.3 million annually from year 6 onwards. By year 5, cumulative income reaches NPR 1.01 million against total costs of NPR 910,000, marking the break-even point.

Over 20 years, the farm accumulates NPR 21.61 million in total income against NPR 2.86 million in costs (including initial investment and maintenance), yielding a net profit of NPR 18.75 million. This model shows that while the first four years operate at a loss, consistent annual profits from year 5 onward (ranging from NPR 215,000 in year 5 to NPR 1.3 million from year 6-20) make it a viable long-term investment with stable returns.

b). High-Density Fig Farming (450 Plants/Acre)

High-density fig farming (450 plants/acre) requires a higher initial investment of NPR 645,000, with annual maintenance costs averaging NPR 150,000 from year 2 onward. The farming operation begins generating income in year 2 (NPR 170,000), with production increasing significantly to reach NPR 2.25 million annually from year 6 through year 20. The break-even point is achieved between years 4-5, when cumulative income surpasses the total investment costs.

Over the 20-year period, the total income reaches NPR 37.045 million, while total costs (including the initial investment and 19 years of maintenance) amount to NPR 3.495 million, resulting in an impressive net profit of NPR 33.55 million. This high-density model demonstrates superior profitability compared to low-density farming, with annual profits growing from NPR 170,000 in year 2 to a stable NPR 2.25 million from year 6 onward, making it an excellent long-term investment for commercial growers with adequate startup capital. The substantial returns justify the higher initial costs, particularly from year 5 onwards when the operation becomes consistently profitable.