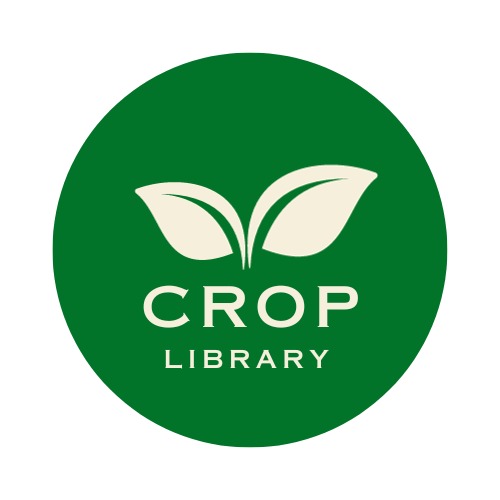

Plant Resistance Mechanisms

Plants, like all living organisms, face constant threats from pathogens. However, they have evolved sophisticated defense mechanisms to protect themselves. The plant resistance mechanisms can be broadly categorized into passive (constitutive) and active (induced) resistance factors. In this blog post, we’ll explore these defense strategies in detail, shedding light on how plants fend off pathogens and ensure their survival.

Passive (Constitutive) Resistance Mechanisms

Plants have evolved a range of pre-existing or “passive” resistance mechanisms that provide a continuous defense against pathogens. These mechanisms are always active, regardless of whether a pathogen is present, and serve as the plant’s first line of defense. They include structural and chemical barriers that inhibit pathogen entry, growth, and spread.

Structural Barriers

1. Cuticle

- The cuticle is a waxy, hydrophobic layer covering the epidermis of aerial plant parts such as leaves, stems, and fruits.

- It serves as a physical shield, preventing the penetration of pathogens, such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses.

- The cuticle also limits water loss, reducing the moist conditions that pathogens often require to thrive.

2. Cell Wall

- Composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, and lignin, the cell wall provides structural support and acts as a robust physical barrier against pathogen entry.

- The presence of lignin and suberin, in particular, enhances the cell wall’s impermeability, making it harder for pathogens to breach.

3. Stomata and Lenticels

- These are natural openings in plant surfaces that facilitate gas exchange but can also serve as entry points for pathogens.

- As a passive defense, plants can close stomata and lenticels to restrict pathogen invasion during unfavorable conditions, such as exposure to microbial attack.

Chemical Barriers

1.Preformed Inhibitors

Plants produce and store chemical compounds that are toxic to potential invaders, such as:

- Glucosides: Organic molecules that release toxic compounds upon enzymatic hydrolysis.

- Saponins: Natural surfactants that disrupt the cell membranes of certain pathogens.

- Alkaloids: Nitrogen-containing compounds that deter herbivores and exhibit antimicrobial activity.

2. Antifungal Proteins

- These proteins, such as chitinases and glucanases, are pre-synthesized and stored in plant tissues.

- They target fungal pathogens by degrading components of the fungal cell wall, such as chitin and glucans.

3. Enzyme Inhibitors

- Plants produce inhibitors that target pathogen-derived enzymes, which are often used by microbes to degrade plant tissues and gain entry.

- For example, protease inhibitors block the activity of proteolytic enzymes secreted by pathogens, preventing them from breaking down plant proteins and tissues.

4. Biological Significance

Passive resistance mechanisms are critical for plant survival, providing a baseline level of protection that does not require active pathogen detection. These defenses:

- Create an inhospitable environment for pathogen growth and reproduction.

- Minimize the likelihood of infection, reducing the need for energy-intensive active responses.

- Serve as a foundation upon which inducible (active) defenses can be triggered if the pathogen successfully overcomes the initial barriers.

Active Resistance Mechanisms

Active resistance mechanisms are dynamic plant defenses that are activated in response to pathogen detection. Unlike passive defenses, these mechanisms are specifically triggered when a pathogen attempts to invade the plant. The response involves structural changes at the site of infection and the production of chemical compounds to inhibit pathogen growth and spread.

Structural Changes

1.Cork Layer and Abscission Layer

- Cork Layer: Infected plant tissues may develop a cork layer, composed of suberized cells, to physically seal off the infection site and prevent pathogen spread.

- Abscission Layer: Plants may form a separation layer of cells around the infected area, causing the infected tissue to detach and fall off. This process, called abscission, limits pathogen progression to other parts of the plant.

2. Cell Wall Modifications: Upon pathogen attack, plants reinforce their cell walls by depositing additional materials such as:

- Callose: A polysaccharide that forms a dense barrier, blocking pathogen access.

- Lignin: A polymer that increases the rigidity and impermeability of cell walls, making them harder for pathogens to penetrate.

- Silica and Phenolic Compounds: Deposited in some cases to further fortify the cell walls.

Chemical Production

1. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

- Plants rapidly produce ROS, such as hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and superoxide (O₂⁻), at the infection site.

- ROS serve dual purposes:

- Directly damaging pathogen cells by causing oxidative stress.

- Acting as signaling molecules to trigger further defense responses, such as the activation of systemic acquired resistance (SAR).

2. Phytoalexins

- These are antimicrobial secondary metabolites synthesized de novo upon pathogen detection.

- Examples include flavonoids, isoflavonoids, and terpenoids.

- Phytoalexins inhibit pathogen growth by disrupting cell membranes, interfering with metabolism, or inhibiting enzyme function.

3. Pathogenesis-Related (PR) Proteins

PR-proteins are a group of proteins produced in response to pathogen attack. They have diverse functions, including:

- Antifungal Activity: Proteins such as chitinases and β-1,3-glucanases degrade the fungal cell wall.

- Antibacterial Activity: Proteins that inhibit bacterial growth or disrupt bacterial membranes.

- Signaling Roles: Some PR-proteins, like defensins, play a role in signaling and activating additional defense pathways.

Biological Significance

Active resistance mechanisms are crucial for combatting pathogens that overcome the plant’s passive defenses. These mechanisms:

- Localize the infection to prevent its spread to healthy tissues.

- Provide a rapid and targeted response to diverse pathogens, including fungi, bacteria, and viruses.

- Trigger systemic defense responses, enhancing the plant’s overall resistance.

By integrating structural changes and chemical defenses, plants achieve a robust and effective response to infection, ensuring survival in pathogen-rich environments.

Induced Defense Mechanisms in Plants

Plants possess sophisticated immune systems that enable them to respond effectively to diverse pathogens. These responses, collectively referred to as induced defenses, are activated only after the plant detects a threat. Induced defenses can be broadly categorized into general resistance and cultivar-specific resistance, each involving distinct mechanisms of pathogen recognition and response.

1.General Resistance

General resistance mechanisms are non-specific and provide broad-spectrum protection against a wide range of pathogens. These defenses are evolutionarily conserved and form the first layer of the plant immune system.

A). Plant Innate Immunity

Basal Defense

- Basal defense refers to the plant’s ability to prevent pathogen colonization through basic physiological and metabolic responses, such as callose deposition, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and antimicrobial compound synthesis.

Non-Host Resistance

- This is a universal defense mechanism in which a plant species is inherently resistant to a pathogen that can infect other species. It involves both structural and biochemical barriers and the activation of immune responses.

B). Pattern-Triggered Immunity (PTI)

PTI is initiated when plants recognize conserved microbial molecules known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Examples of PAMPs include:

- Flagellin (a bacterial protein).

- Chitin (a component of fungal cell walls).

- Recognition of PAMPs occurs through specialized cell-surface receptors called pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). These receptors trigger signaling cascades that lead to defense responses, including:

- Reinforcement of cell walls through callose deposition.

- Activation of ROS production and signaling molecules like salicylic acid (SA).

- Induction of antimicrobial compound synthesis to limit pathogen growth.

2. Cultivar-Specific and Gene-for-Gene Resistance

Cultivar-specific resistance in plants is a highly specialized form of defense where specific plant genotypes resist specific pathogen strains. This phenomenon is primarily explained by the gene-for-gene hypothesis, which underpins many plant-pathogen interactions.

A). Gene-for-Gene Hypothesis

The gene-for-gene hypothesis, first proposed by H.H. Flor, describes a specific interaction between plant resistance (R) genes and pathogen avirulence (Avr) genes.

- R genes: Encode proteins in plants that recognize pathogen-derived effector molecules (encoded by Avr genes).

- Avr genes: Pathogen genes that produce effectors intended to suppress plant immunity or facilitate infection.

When an R protein in the plant recognizes an Avr effector, the plant’s immune system activates, leading to a robust defense response that often includes:

- Hypersensitive Response (HR): Localized programmed cell death to restrict pathogen spread.

- Effector-Triggered Immunity (ETI): A strong and targeted immune response.

If no recognition occurs (e.g., due to a mutation in the R or Avr gene), the pathogen can infect the plant, causing disease.

This specific recognition explains why resistance is often effective only against particular pathogen strains or races.

B). Horizontal vs. Vertical Resistance

Resistance mechanisms can be classified into horizontal resistance and vertical resistance based on their specificity, genetic basis, and durability.

i). Horizontal Resistance

- Broad-Spectrum Defense: Effective against a wide range of pathogen strains.

- Polygenic: Governed by multiple genes, each contributing incrementally to overall resistance.

- Durable: Less susceptible to being overcome by evolving pathogens because it does not rely on a single gene-pathogen interaction.

- Mechanism: Typically involves basal defenses such as pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) and general plant innate immunity.

Advantages

- Long-lasting and stable resistance.

- Widely used in breeding programs for sustainable crop protection.

Limitations

- Resistance levels may not be as high as vertical resistance.

ii). Vertical Resistance

- Race-Specific Defense: Effective only against specific pathogen races carrying matching Avr genes.

- Monogenic: Controlled by one or a few major R genes.

- Highly Effective: Can completely block infection when the corresponding Avr gene is present in the pathogen.

- Mechanism: Involves effector-triggered immunity (ETI), often resulting in hypersensitive response (HR).

Advantages

- Provides strong and immediate protection against specific pathogen races.

Limitations

- Vulnerability to Pathogen Evolution: Pathogens can evolve new strains that evade recognition by R genes, rendering resistance ineffective.

- Short-Lived Durability: Resistance may break down in the presence of rapidly evolving pathogens.

C). Biological and Agricultural Implications

- Horizontal Resistance is essential for durable crop protection and is favored in breeding programs to reduce the risk of breakdown of resistance.

- Vertical Resistance is valuable in combating specific pathogen outbreaks but requires careful management to prevent rapid pathogen adaptation.

To achieve sustainable disease management, integrated resistance strategies combining both types of resistance are often employed in modern agriculture. This approach helps balance the immediate effectiveness of vertical resistance with the long-term stability of horizontal resistance.

Comparison of Horizontal and Vertical Resistance

| Feature | Horizontal Resistance | Vertical Resistance |

| Specificity | Broad-spectrum | Race-specific |

| Genetic Basis | Polygenic | Monogenic |

| Durability | Long-lasting | Short-lived |

| Effectiveness | Moderate | High against specific races |

| Pathogen Interaction | Non-specific mechanisms | Gene-for-gene interaction |

| Application | Preferred for sustainable management | Used for targeted outbreaks |

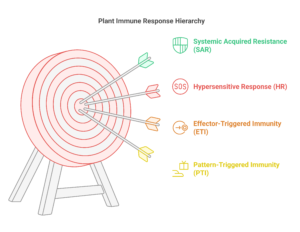

The Plant Immune Response: A Multi-Layered Defense System

Plants, though stationary, are far from defenseless. They have evolved a sophisticated immune system with multiple layers of defense to protect themselves from pathogens. This immune response relies on an intricate interplay of recognition, signaling, and action mechanisms that detect and neutralize threats. Plants utilize a combination of passive defenses, such as structural barriers like the cuticle and cell walls, which act as physical shields against pathogen entry, and chemical inhibitors, including performed compounds like glucosides and alkaloids, that deter or eliminate potential invaders. In addition to these pre-existing defenses, plants employ active mechanisms that involve complex immune responses to fight infections and mitigate damage.

Understanding the intricacies of these defense mechanisms not only highlights the remarkable resilience of plants but also provides crucial insights for advancing crop protection and sustainable agriculture. By studying how plants naturally fend off pathogens, researchers can devise innovative strategies to combat plant diseases, boost agricultural productivity, and contribute to global food security. Among the active responses, key components such as Pattern-Triggered Immunity (PTI), Effector-Triggered Immunity (ETI), the Hypersensitive Response (HR), and Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR) are critical in providing both immediate and long-term protection against diverse pathogens.

1. PTI (Pattern-Triggered Immunity): The First Line of Defense

Pattern-Triggered Immunity (PTI) is the plant’s initial response to pathogen invasion. It is triggered when the plant recognizes Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs)common molecular signatures found in pathogens, such as bacterial flagellin or fungal chitin. These PAMPs are detected by Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs) located on the plant cell surface.

- Recognition of PAMPs: PRRs bind to PAMPs, initiating a signaling cascade that activates the plant’s immune response.

- Immune Responses Activated by PTI:

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production: ROS are generated to directly damage the pathogen and act as signaling molecules to amplify the immune response.

- Cell Wall Fortification: The plant strengthens its cell walls by depositing callose and lignin, creating a physical barrier to prevent pathogen entry.

- Activation of Defense Genes: PTI triggers the expression of genes involved in defense, such as those encoding antimicrobial proteins.

PTI is a broad-spectrum defense mechanism, providing resistance against a wide range of pathogens. However, some pathogens can suppress PTI by secreting effectors, leading to the next layer of defense: Effector-Triggered Immunity (ETI).

2. ETI (Effector-Triggered Immunity): A Stronger, Targeted Response

When pathogens successfully suppress PTI by secreting effectors, plants deploy a more specific and potent defense mechanism known as Effector-Triggered Immunity (ETI). ETI is mediated by Resistance (R) proteins inside the plant cells, which recognize specific pathogen effectors.

- Recognition of Effectors: R proteins detect pathogen effectors, often leading to a highly localized and intense immune response.

- Hypersensitive Response (HR): A hallmark of ETI, HR involves the rapid death of cells at the infection site. This localized cell death limits the spread of the pathogen by creating a physical barrier of dead tissue.

- Amplification of Defense Signals:ETI often involves the production of signaling molecules like salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET), which further enhance the plant’s immune response.

ETI is a more targeted and robust defense mechanism compared to PTI, but it is also more specific, often effective only against certain pathogen strains.

3. HR (Hypersensitive Response): Sacrificing Cells to Save the Plant

The Hypersensitive Response (HR) is a critical component of ETI, where the plant sacrifices a small number of its own cells to prevent the spread of the pathogen.

- Localized Cell Death: Cells at the infection site undergo programmed cell death, effectively trapping the pathogen and preventing its spread to healthy tissues.

- Role of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): ROS play a dual role in HR, both as direct antimicrobial agents and as signaling molecules that trigger cell death.

- Formation of a Physical Barrier: The dead cells form a barrier that isolates the pathogen, limiting its ability to infect other parts of the plant.

HR is a dramatic but effective strategy that highlights the plant’s ability to make calculated sacrifices for its overall survival.

4. SAR (Systemic Acquired Resistance): Long-Lasting Immunity

After successfully defending against a pathogen, plants can develop a long-lasting, system-wide immunity known as Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR). SAR primes the plant to respond more effectively to future attacks.

- Activation of SAR: SAR is triggered by signaling molecules like salicylic acid (SA), which are produced at the infection site and transported throughout the plant.

- Production of PR Proteins: SAR involves the systemic production of Pathogenesis-Related (PR) Proteins, which have antimicrobial properties and enhance the plant’s overall resistance.

- Long-Lasting Protection: SAR provides broad-spectrum resistance against a wide range of pathogens, making the plant more resilient to future infections.

SAR is a key mechanism by which plants “remember” past infections and prepare for future threats, ensuring long-term survival.

Also Read About: How do Plant Virus Enter in to Plant Cell

By Trapping Harmful Substances in the Vacuole: A Strategic Defense Mechanism

In addition to the immune responses described above, plants have another ingenious defense strategy: the ability to isolate harmful substances within vacuoles. Vacuoles are membrane-bound organelles that act as storage compartments, allowing plants to safely sequester toxic compounds until they are needed for defense.

- Role of the Vacuole: The vacuole stores defense-related compounds, such as phytoalexins and reactive oxygen species (ROS), in an inactive form. When a pathogen attacks, these compounds can be released to neutralize the threat.

- Ionization and Binding: Plants use processes like ionization and binding to enhance the potency of these compounds while minimizing their own exposure to toxicity.

- Case Study: Unsaturated Lactones: Compounds like tuliposid B are stored in vacuoles and released to combat pathogens like Botrytis cinerea. These compounds disrupt pathogen enzymes, effectively neutralizing the threat.

By trapping harmful substances in vacuoles, plants transform potential threats into strategic defenses, showcasing their remarkable adaptability and resilience.

Recognizing and Responding to Pathogens

Plants detect pathogens through a sophisticated immune system involving two main pathways:

- Pattern-Triggered Immunity (PTI): Recognizes common microbial patterns.

- Effector-Triggered Immunity (ETI): Targets specific pathogen effectors and often results in a hypersensitive response (HR) or programmed cell death (PCD).

Signal Transduction and Activation of Resistance

Receptor proteins like Xa21 in rice illustrate how plants recognize pathogens and activate defenses. These receptors have distinct domains:

- Leucine-Rich Repeat (LRR):Recognizes pathogen signals.

- Kinase Domain:Triggers downstream signaling, including ROS production, PR protein activation, and cell wall reinforcement.

Phytoalexins: The Last Line of Defense

Phytoalexins, low-molecular-weight antimicrobial compounds, are produced only upon pathogen infection. They accumulate rapidly at infection sites in concentrations high enough to stop pathogen growth. Their specificity and quick deployment make them essential for plant survival.

Conclusion

Plants are far from passive victims in the face of pathogens. By isolating harmful substances in vacuoles, deploying chemical defenses like the mustard oil bomb, and activating sophisticated immune responses, they demonstrate extraordinary resilience and adaptability. These strategies not only protect the plant but also ensure its survival in hostile environments—testament to the ingenuity of nature’s design.

Understanding these mechanisms could pave the way for developing disease-resistant crops, contributing to global food security.