Introduction

Tilapia farming involves the cultivation of a group of predominantly freshwater, warm-water fish belonging to the family Cichlidae, native to Africa and the Middle East. These fish are highly valued in aquaculture due to their hardiness, rapid growth, and palatable flesh, making them the second most important group of farmed fish worldwide after carps. The most commercially significant genera in tilapia farming include Oreochromis (maternal mouthbrooders), Sarotherodon (paternal or biparental mouthbrooders), and Tilapia (substrate spawners).

Biology of Tilapia

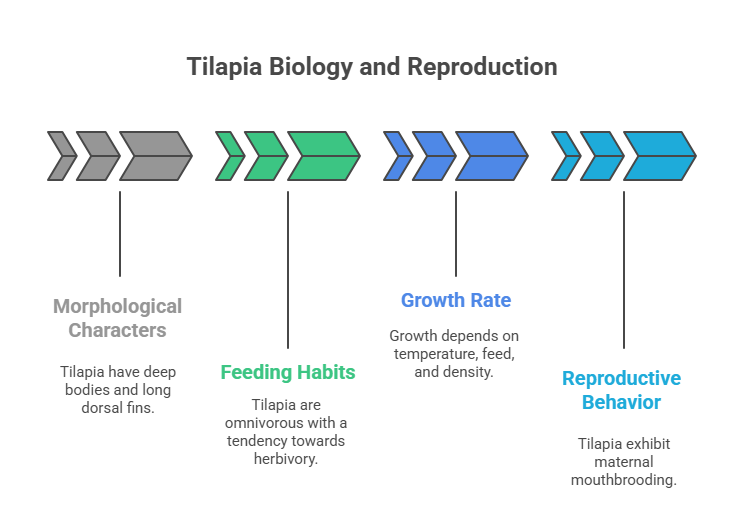

a). Morphological Characters

Tilapia are deep-bodied, laterally compressed fish with a long dorsal fin. The dorsal fin has spiny rays in the front portion. They have cycloid scales and a continuous lateral line that is interrupted. Their coloration varies by species, sex, and environment, but is generally grey, silver, or yellowish, often with vertical banding when young or stressed.

Mouths are protrusible, aiding in bottom feeding. Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), the most widely cultured species, often has vertical stripes on the caudal fin and pinkish-red margins on the dorsal fin.

b). Feeding Habits

Tilapia are primarily omnivorous with a strong tendency toward herbivory and planktivory, possessing a long, coiled intestine—often six to eight times their body length—adapted for digesting plant matter.

Their natural diet includes phytoplankton and algae, which they efficiently filter using specialized gill rakers, periphyton that they graze on attached to submerged surfaces, as well as aquatic plants, detritus, and benthic invertebrates.

This low trophic level makes tilapia farming efficient, as they can utilize the natural productivity of ponds, while in intensive farming systems they are typically fed formulated pellet feeds containing 25–35% protein.

c). Growth Rate

Growth is highly dependent on temperature, feed quality, and stocking density. Under optimal conditions (28-30°C), male Nile tilapia can reach 250-350 grams in 5-7 months from fry. Males grow 30-40% faster than females, a key reason for the preference for all-male monosex culture. Selective breeding programs (e.g., GIFT strain – Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia) have significantly enhanced growth rates and disease resistance.

d). Reproductive Behavior

Most farmed tilapia species (Oreochromis spp.) exhibit maternal mouthbrooding, a reproductive behavior with profound implications for aquaculture. The process begins with males establishing territories and building circular nests on the pond bottom. A female enters a nest, lays her eggs, and immediately retrieves them into her mouth.

The male then deposits sperm (milt) over the nest, which the female sucks in to fertilize the eggs internally. She subsequently incubates the fertilized eggs and the developing fry in her buccal cavity for 10–14 days, providing exceptional parental protection. While this behavior ensures very high fry survival and allows for early maturation (at just 4–5 months of age), it directly leads to severe pond overpopulation, resulting in stunted growth from excessive competition for food.

To overcome this inherent challenge, commercial tilapia farming universally relies on monosex culture, predominantly all-male populations, which are created through techniques such as hormonal sex reversal of fry, hybridization of specific species, or manual sorting.

Water Quality Management

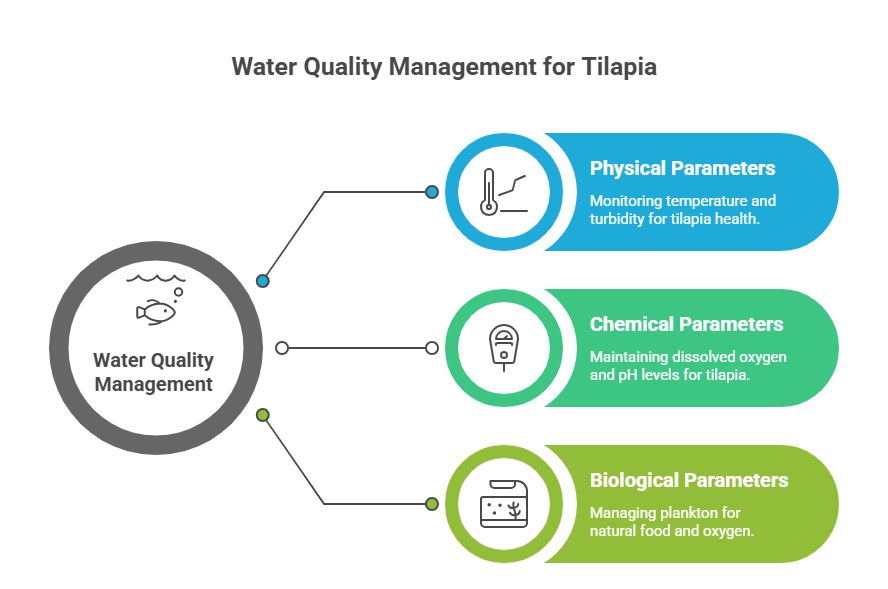

a). Physical Parameters

Water quality management for tilapia involves careful monitoring of physical parameters, particularly temperature and turbidity. Tilapia are thermophilic, thriving optimally between 25–32°C; growth halts below 20°C, they become stressed and disease-prone below 16°C, and mortality occurs at 12–13°C, necessitating thermal regulation through greenhouse systems or measures against thermal pollution in temperate regions.

Turbidity should ideally be low, as suspended clay particles reduce light penetration, limiting phytoplankton growth—a natural food source—and can irritate fish gills. However, turbidity resulting from plankton blooms, or “green water,” is desirable as it indicates high productivity.

b). Chemical Parameters

Chemical water quality management for tilapia requires maintaining adequate dissolved oxygen (DO) and pH levels. Tilapia need a minimum DO of 3–5 mg/L for survival, but levels above 5 mg/L are essential for good growth; they are relatively tolerant of low DO and may gulp air at the surface, with dawn being a critical period due to nighttime respiration by plants and animals, making aeration through paddlewheels or aerators essential in intensive systems.

The optimal pH range is 6.5 to 9.0, as values below 6.5 reduce productivity and cause acid stress, while pH above 9—often occurring in afternoons from high phytoplankton photosynthesis—can become toxic, so regular liming is necessary to stabilize pH.

c). Biological Parameters

Biological water quality management for tilapia emphasizes the role of plankton, which forms the foundation of semi-intensive farming. Phytoplankton, microscopic plants, act as primary producers, with a moderate greenish water color indicating a healthy bloom that provides natural food and oxygen, while dominance of blue-green algae is undesirable.

Zooplankton, including rotifers, cladocerans, and copepods, serve as excellent live food for tilapia fry and fingerlings, and the ratio and density of both phytoplankton and zooplankton are carefully managed through fertilization.

Pond Management

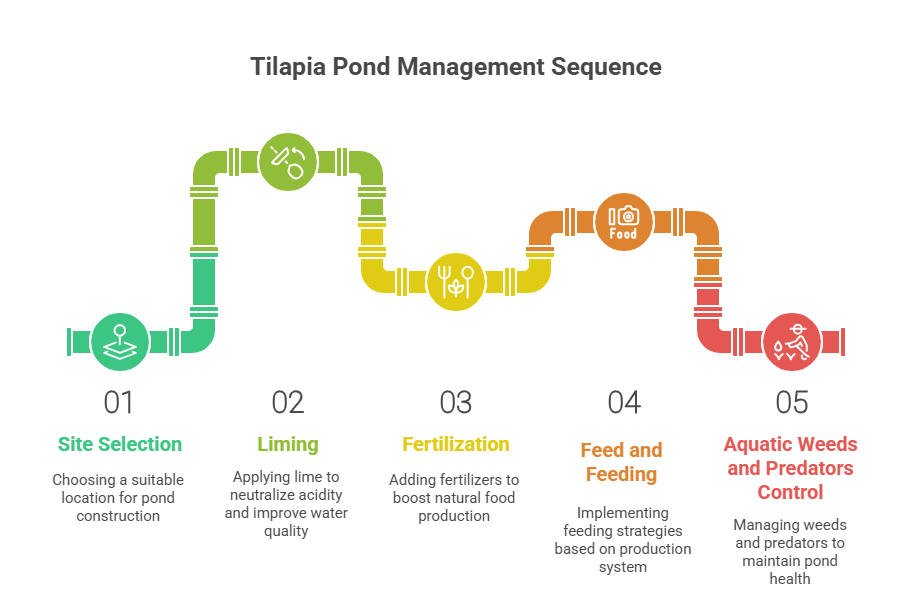

a). Site Selection for Pond Construction

Site selection for pond construction involves considering several key factors, including soil type—preferably clay-loam with more than 20% clay to retain water—availability of a reliable and clean water source free from pollutants, gentle topography to facilitate drainage and pond construction, and good accessibility for inputs and access to markets.

b). Liming

The application of agricultural lime (CaCO₃) or quick lime (CaO) to the pond bottom and water. Purposes: Neutralize pond acidity, increase pH, enhance the effect of fertilizers, improve water clarity, and add calcium for fish physiology.

c). Fertilization

Fertilization in tilapia farming aims to boost natural food production, primarily plankton, through the use of both organic and inorganic fertilizers. Organic fertilizers, such as cow, chicken, or pig manure, are applied as a base before filling the pond, releasing nutrients slowly and promoting a diverse food web.

Inorganic fertilizers, including N-P-K compounds like urea and Triple Super Phosphate, are applied periodically to maintain a healthy plankton bloom, with the nutrient ratio—often 4:1 for nitrogen to phosphorus—carefully managed to prevent undesirable blue-green algae proliferation.

d). Feed and Feeding

Feed and feeding strategies in tilapia farming vary with the production system. In extensive and semi-intensive systems, fish rely primarily on natural food enhanced through fertilization, while in semi-intensive to intensive systems, supplemental feeding with floating pellets containing 28–32% protein is provided.

Feeding is carried out at fixed times, typically 2–3 times daily, at 3–5% of body weight, with adjustments made based on actual consumption and water temperature.

e). Aquatic Weeds and Predators Control

Control of aquatic weeds and predators in tilapia farming is essential for maintaining pond health and productivity. Weeds—emergent, floating, and submerged—compete for nutrients, deplete oxygen at night, and hinder fishing, and can be managed through manual removal, maintaining a strong plankton bloom to shade the pond bottom and inhibit growth, or biological control such as introducing grass carp.

Predators such as birds, snakes, frogs, and carnivorous fish can be managed by installing pond netting, removing vegetation from pond embankments to keep snakes away, and ensuring inlet water is properly screened.

Classification of Tilapia Farming Systems (TFS)

Tilapia farming systems range from simple backyard ponds to high-tech recirculating systems. The choice depends on capital, technology, and market objectives.

On the Basis of Intensity

a). Extensive

Large ponds (>1 ha), low stocking density (<5,000 fish/ha), no supplemental feeding, relies entirely on natural food. Low yield (1-2 tons/ha/year).

b). Semi-Intensive

Moderate stocking density (10,000-30,000 fish/ha) uses fertilization and supplemental feeding. Yield: 5-10 tons/ha/year. The most common system globally.

c). Intensive

High stocking density (>30,000 fish/ha in ponds; 50-150 kg/m³ in tanks/cages), complete dependence on high-quality artificial feed, and mandatory aeration. Very high yield (e.g., 100-300 tons/ha/year in cages).

d). Super-Intensive

Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) with biofiltration, ozonation, etc. Maximum environmental control, highest density, and highest investment.

On the Basis of Enclosure

a). Pond Culture

The traditional and most widespread method.

b). Cage Culture

Cages (net pens) are installed in existing water bodies (lakes, reservoirs, rivers). Allows use of public waters, easy harvesting, but depends on water body quality.

c). Tank/Raceway Culture

Using concrete, fiberglass, or plastic tanks. Often integrated with water treatment (flow-through or RAS). High degree of management control.

d). Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS)

Advanced systems where water is treated (mechanically, biologically, and chemically) and reused. Enables location independence and minimal water exchange.

On the Basis of Fish Species

a). Monoculture

Farming only one species, usually all-male Nile tilapia, to maximize uniform growth and yield.

b). Polyculture

Tilapia are stocked with complementary species. E.g., with Catfish (bottom feeder) and Carps (mid-water feeder) to utilize different feeding niches and increase total pond productivity.

On the Basis of Integration

a). Integrated Agriculture-Aquaculture (IAA)

E.g., Rice-Fish Culture: Tilapia grown in rice paddies; fish provide fertilizer, eat pests, and yield extra protein.

b). Livestock-Fish Integration

Pig-Tilapia, Duck-Tilapia, Chicken-Tilapia. Animal sheds are built over or adjacent to ponds. Manure directly fertilizes the pond, producing plankton for tilapia. A highly efficient nutrient recycling model.

c). Aquaponics

A contemporary system in which nutrient-rich tilapia effluent, high in ammonia, is directed through hydroponic beds where plants such as lettuce or basil absorb the nutrients, after which the purified water is returned to the fish tanks. This method provides a sustainable, nearly zero-waste approach.

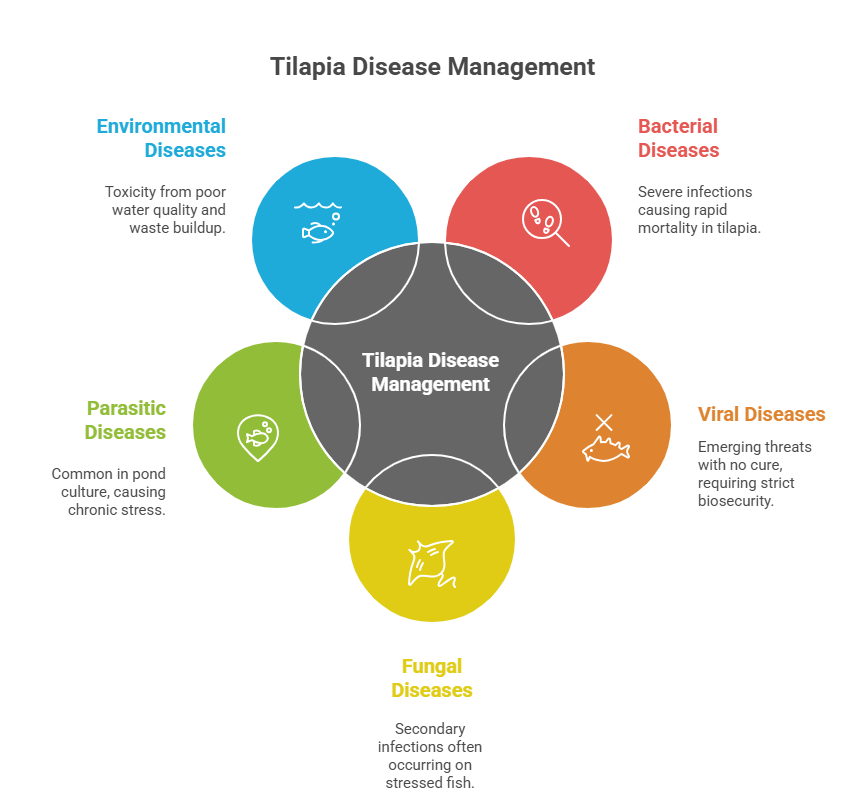

Common Fish Diseases and Parasites

Tilapia are relatively hardy, but under stressful conditions (poor water quality, overcrowding, handling, or suboptimal temperature), they become highly susceptible to pathogens. Disease management focuses on prevention through good husbandry.

Diseases are categorized by causative agent: Bacterial, Viral, Fungal, Parasitic, and Environmental.

Bacterial Diseases

These are often the most severe, causing rapid mortality.

i). Streptococcosis (Streptococcus iniae, S. agalactiae)

Streptococcosis is one of the most serious diseases in intensive tilapia farming, causing significant economic losses. Infected fish exhibit “spinning disease,” swimming erratically in spirals or corkscrew patterns. Other clinical signs include lethargy, loss of appetite, pop-eye (exophthalmia), darkened skin, and hemorrhages at the base of fins and opercula.

Internally, inflammation of the brain lining (meningitis) is common. Disease outbreaks are often triggered by high water temperatures (>28°C), high organic loads, overstocking, and handling stress.

Management focuses on prevention and careful use of antibiotics under veterinary supervision. Vaccination is effective in some regions and should be implemented where available. During outbreaks, oxytetracycline can be used at 75–100 mg per kg of fish body weight per day in feed for 7–10 days, or florfenicol at 10 mg per kg body weight per day for 10 consecutive days, following veterinary guidance.

Maintaining good water quality, reducing stress, and avoiding overcrowding are critical to preventing disease recurrence. Improper or prolonged antibiotic use should be avoided to reduce the risk of antimicrobial resistance.

ii). Columnaris Disease (Flavobacterium columnare)

Columnaris Disease (Flavobacterium columnare) is a highly infectious bacterial disease commonly affecting tilapia and other freshwater fish. Infected fish show yellowish-white or pale patches on the skin, fins, or gills, often forming a “saddle-back” appearance near the dorsal fin.

Fins become frayed and eroded, and gills may turn necrotic with a mottled brown coloration. Lesions progress rapidly, and stressed fish or those exposed to high organic loads, elevated temperatures, or physical injuries are particularly susceptible.

Management of columnaris disease focuses on early intervention and maintaining good water quality. Salt baths at 10–20 ppt for 5–10 minutes can be effective in early infections. Additionally, potassium permanganate can be applied at 2–3 mg/L for 30–60 minutes, or copper sulfate at 0.3–0.5 mg/L as a bath treatment, following veterinary guidance. Reducing stress, improving water conditions, and avoiding overcrowding are essential to prevent outbreaks and limit disease progression.

iii). Motile Aeromonas Septicemia (MAS) / Hemorrhagic Septicemia (Aeromonas hydrophila)

Motile Aeromonas Septicemia (MAS) / Hemorrhagic Septicemia, caused by Aeromonas hydrophila, is an opportunistic bacterial disease that mainly affects weak or stressed tilapia. Infected fish commonly show skin ulcers, red hemorrhagic patches on the body and fin bases, swollen abdomen (dropsy), and protruded eyes (exophthalmia).

Outbreaks usually occur under poor water quality—especially low dissolved oxygen, high ammonia levels—along with overcrowding and handling stress, which make fish more susceptible.

Management focuses on correcting underlying water quality problems while providing targeted treatment. During confirmed infections, oxytetracycline can be given at 75–100 mg per kg fish body weight per day for 7–10 days, or florfenicol at 10–15 mg per kg body weight per day for 10 days, strictly under veterinary supervision. Feed-based probiotics can also be incorporated to improve gut health and enhance fish immunity. Preventing stress, maintaining clean ponds, and avoiding overcrowding are essential to reducing recurrence.

Viral Diseases

Tilapia Lake Virus (TiLV)

Tilapia Lake Virus (TiLV) is a serious and emerging viral disease affecting tilapia worldwide and is officially recognized by the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH). Infected fish often show loss of appetite, lethargy, skin erosions, cloudy or protruded eyes, and swollen abdomen, with juveniles experiencing especially high mortality rates.

The virus spreads easily through horizontal transmission (fish-to-fish) and may also transmit vertically from broodstock to their offspring, making the movement of infected seed a major source of outbreaks.

Since no cure or commercial vaccine currently exists, control depends entirely on strict biosecurity measures. Farmers must source TiLV-free seed, quarantine new arrivals, disinfect ponds and equipment, and avoid mixing batches of fish. In severe cases, culling and safe disposal of infected stocks may be necessary to prevent the virus from spreading to healthy populations.

Fungal Diseases

These typically occur as secondary infections on wounds or stressed fish.

Saprolegniasis (Water Mold)

Saprolegniasis is a fungal disease caused primarily by Saprolegnia species and is recognized by its cotton-like white or grey growth on the skin, fins, gills, or eggs, often beginning at areas of physical injury. The infection becomes more common and severe under low temperatures, poor water quality, and stress from handling, all of which weaken the fish’s natural defenses.

Management focuses on improving environmental conditions and applying safe, effective treatments. Salt baths at 10–20 ppt for 5–10 minutes can help control early infections, while hydrogen peroxide at 50–75 mg/L for 30 minutes may be used under veterinary guidance.

Where legally permitted, malachite green can be applied at 0.1–0.2 mg/L for 30–60 minutes, although its use is restricted in many countries due to safety concerns. Maintaining good water quality and reducing stress are essential for successful recovery.

Parasitic Diseases

Parasites are common in pond culture and often cause chronic stress rather than acute mortality.

a). Protozoan Parasites

Protozoan parasites commonly affect tilapia, with Ichthyophthirius multifiliis (“Ich” or White Spot) being one of the most recognizable. Infected fish develop tiny white spots resembling grains of salt on the skin, fins, and gills, accompanied by flashing (rubbing against surfaces) and clamped fins.

Severe gill infections can be fatal. Management typically involves formalin or salt baths, and since the parasite’s life cycle is temperature-dependent, slightly increasing water temperature helps speed up the free-swimming stage, making treatment more effective.

Another frequent protozoan parasite is Trichodina, a disc-shaped ciliate that thrives in poor water quality. Affected fish show a bluish-white sheen or excess mucus on the skin along with flashing behavior.

Treatment includes salt or formalin baths, but long-term control relies on improving water conditions, reducing organic load, and maintaining proper sanitation to prevent reinfestation.

b). Monogenean Trematodes (Flukes)

Monogenean trematodes, including Gyrodactylus (skin fluke) and Dactylogyrus (gill fluke), commonly infect tilapia and cause significant irritation to the skin and gills. Infected fish show excessive mucus production, swollen or pale gills due to hyperplasia, lethargy, and respiratory distress such as gasping at the water surface. These parasites are usually confirmed by microscopic examination, as they are too small to be seen with the naked eye.

Management relies on effective antiparasitic treatments and improving water conditions. Praziquantel is highly effective and may be administered at 2–5 mg/L as a prolonged bath for 24 hours or 50–75 mg/kg in feed for 3–5 days, under veterinary guidance. Salt treatments can also help reduce mucus and dislodge some flukes, typically at 5–10 ppt for 10–15 minutes. Maintaining good water quality and reducing stress are essential to prevent reinfection.

c). Crustacean Parasites

Crustacean parasites such as Lernaea spp. (Anchor Worm) are easily recognized because the parasites are visible to the naked eye as greenish-white, thread-like structures embedded in the skin, muscles, or fin bases. Infected fish develop red, inflamed ulcers around the attachment site, often leading to secondary bacterial or fungal infections. These parasites cause irritation, reduced feeding, and overall stress, making early detection important for effective control.

Management involves both physical removal and pond-level treatment. Individual fish can be treated by manually removing the parasites with disinfected forceps, followed by applying an antiseptic.

For pond treatment, diflubenzuron (an organophosphate) is effective at 0.03–0.1 mg/L, depending on product formulation and veterinary advice. Salt dips at 10–20 ppt for 5–10 minutes can help reduce irritation and combat secondary infections. Maintaining good water quality and regular pond monitoring helps prevent reinfestation.

Environmental & Nutritional Diseases

Ammonia/Nitrite Toxicity

Ammonia and nitrite toxicity occur when waste buildup, overfeeding, and poor biofiltration cause harmful nitrogen compounds to accumulate in the water. Affected fish show brownish-red gills from ammonia burns, gasping at the surface or near water inlets, lethargy, and sudden unexplained mortality.

In the case of nitrite poisoning, fish develop “brown blood disease,” where the blood becomes chocolate brown due to impaired oxygen transport. These conditions are common in overcrowded or poorly managed ponds.

Management requires rapid action to prevent further losses. Immediate partial water exchange is the most effective emergency response, followed by reducing or stopping feeding until levels stabilize. For nitrite toxicity, salt (sodium chloride) should be applied at 0.1–0.3% (1–3 g/L) to block nitrite absorption through the gills. Improving aeration, cleaning sediments, and strengthening biofiltration are essential long-term measures to prevent recurrence and maintain stable water quality.

Also Read: Common Carp Characteristics

Pingback: Tilapia Farming Profit Per Acre -