Tamarind Farming

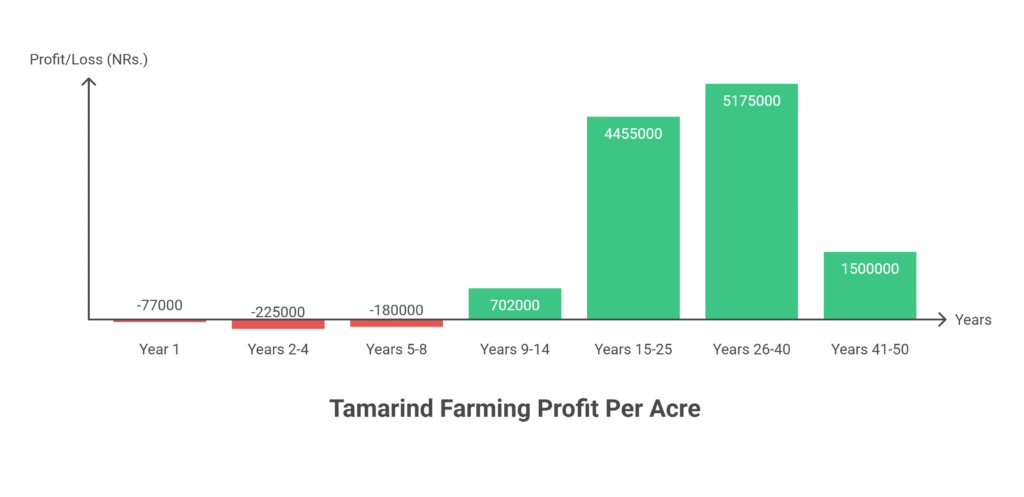

Tamarind (Tamarindus indica) is a long-lived, drought-tolerant leguminous tree primarily cultivated for its edible sour-sweet pulp (used in culinary, beverages, confectionery) and valuable timber. Tamarind farming profit per acre increases significantly over time, making it a highly rewarding long-term investment. Although the initial years (1–4) involve high establishment and maintenance costs with no returns, profitability begins gradually from the fifth year as trees start yielding.

By the commercial phase (years 9–14), profits grow steadily, and peak returns are achieved between years 15 and 40. With consistent maintenance, a well-managed orchard can generate substantial cumulative profits, especially during the mature and late-yield phases, highlighting the long-term economic potential of tamarind cultivation.

Land Preparation

Land preparation for tamarind cultivation begins with thoroughly clearing the site, removing all unwanted vegetation, stones, tree stumps, and deep-rooted bushes to ensure an obstruction-free planting area. This is followed by deep plowing to a depth of 45–60 cm to break compact soil layers, enhance aeration, and support deep root growth—critical for tamarind’s drought tolerance.

Harrowing is done next to break up large soil clods and achieve a finer tilth that facilitates easy pit digging and strong initial root establishment. After soil refinement, land leveling is carried out to ensure a uniform surface or appropriate contouring on sloped land to minimize erosion and avoid waterlogging in low-lying areas.

The field is then laid out and marked according to the selected spacing system (square, rectangular, or hexagonal), ensuring proper plant population and canopy development. Finally, pits are dug at the marked spots well in advance of planting, allowing time for pit weathering and preparation as described under the pit preparation guidelines.

Soil Type

Alluvial soils, sandy loams, loams, clay loams, and even rocky or gravelly soils, as long as the drainage is good, can support tamarind, which thrives in deep, well-drained soils. Given how susceptible tamarind is to waterlogging, which can result in deadly root rot, proper drainage is essential. In addition, the tree can tolerate a pH range of 4.5 to 9.0, which is slightly acidic to alkaline, however 6.0 to 7.5 is the ideal range. Furthermore, tamarind exhibits a modest level of saline tolerance, which makes it a promising crop for some marginal and coastal regions.

Climatic Requirements

| Parameter | Requirement | ||

| Climate | Tropical and subtropical; cannot tolerate frost. | ||

| Temperature | Optimal: 25°C to 35°C. Mature trees tolerate up to 46°C briefly. Young trees damaged below -1°C to -2°C. | ||

| Rainfall | Survives with as little as 400–500 mm/year once established. Best performance at 750–1500 mm/year, well-distributed. | ||

| Sunlight | Requires full sun (minimum 6–8 hours direct sunlight per day) for ideal growth and fruiting. | ||

| Humidity | Tolerates both low and high humidity, suitable for arid and coastal tropical areas. | ||

| Wind | Wind-tolerant; suitable as windbreak. Strong winds during flowering may reduce pollination and cause fruit drop. | ||

Major Cultivars

Tamarind cultivars are primarily distinguished by their pulp characteristics, including sweetness, sourness, color, fiber content, and pod size or yield. While true named cultivars are relatively rare, most tamarind grown commercially consists of regional selections chosen for their superior traits.

There are two major types of tamarind based on flavor. The Sweet Tamarind variety has lower acidity and higher sugar content, making it suitable for fresh consumption or dessert use. Common examples include ‘Manila Sweet’ from the Philippines and ‘Makham Wan’ from Thailand. Named sweet varieties are becoming increasingly available in global markets. The Sour Tamarind type, rich in tartaric acid, is the traditional variety widely used in cooking and food processing industries. Most wild and cultivated trees belong to this group.

Regional selections play a vital role in tamarind cultivation. Farmers often choose superior local trees based on several traits such as high pulp-to-seed ratio, deep brown or reddish pulp color, low fiber, and strong, tangy flavor. Other important factors include high yield, large pod size, and desirable tree habits like disease resistance and upright growth.

Examples of regional selections include several Indian varieties such as ‘Pratisthan’ (Maharashtra – high yielding), ‘Urigam’ (Tamil Nadu – sweet type), ‘Yogeshwari’ (high pulp), PKM 1, Hasanur, Tumkur Prathisthan, DTS 1, and Ajanta. In Thailand, popular cultivars include ‘Sithong’ (golden pod) and ‘Sri Tong’, known for export quality. Other noteworthy types are ‘Cambodiana’ and ‘Australian Sweet’, suited to different growing regions and market demands.

Planting

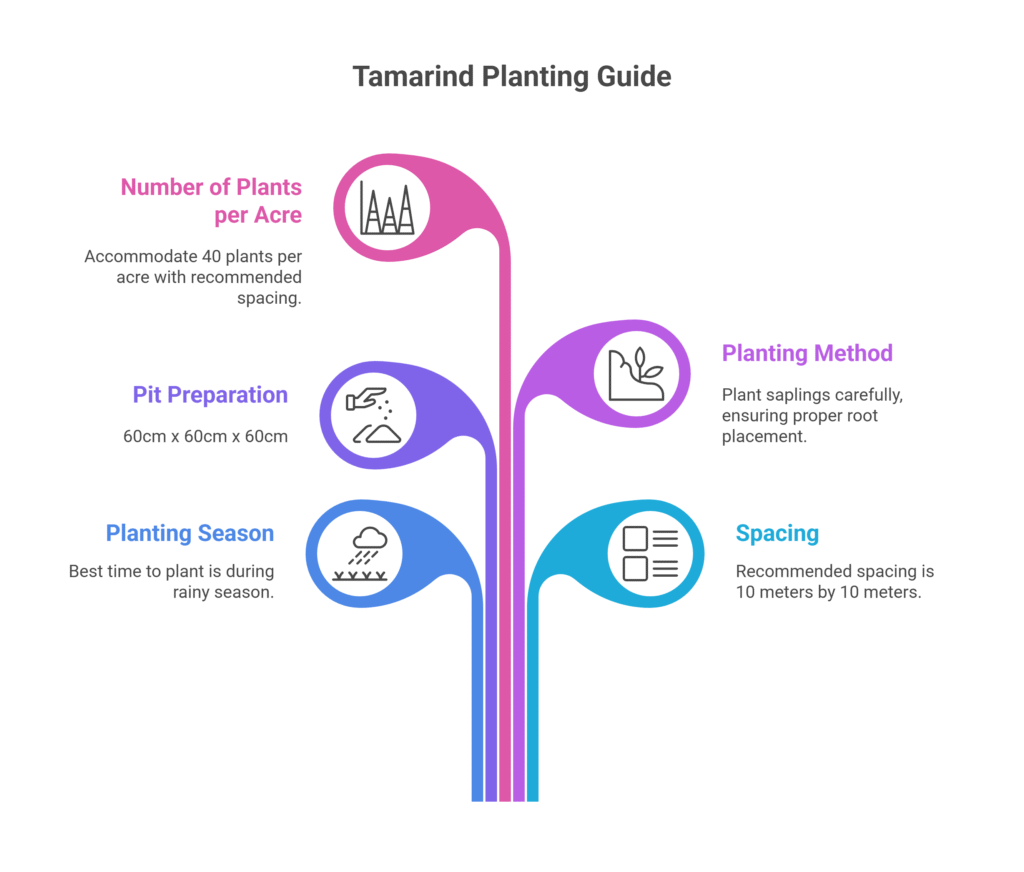

a). Planting Season

The beginning of the rainy season, which is usually June to September, is the best time of year to grow tamarind. During this time, planting guarantees natural soil moisture, which promotes strong root development, lessens the need for frequent irrigation, and lessens transplant shock in young seedlings.

b). Spacing

Tamarind trees require wide spacing to accommodate their large, spreading canopy as they mature. For standard orchards, a spacing of 10 meters × 10 meters is commonly recommended, allowing for about 40 trees per acre. This layout ensures sufficient sunlight, air circulation, and ease of management as the trees grow.

c). Pit Preparation

Pit preparation for tamarind planting should begin at least 4–6 weeks before transplanting, with each pit measuring a minimum of 60 cm × 60 cm × 60 cm. During digging, separate the topsoil and subsoil.

Prepare a refill mixture by combining the topsoil with 15–20 kg of well-rotted farmyard manure (FYM) or compost, 500 g of Single Super Phosphate (SSP), 200–300 g of Muriate of Potash (MOP), along with 100 g of neem cake to repel termites and soil pests, and 100 g of Trichoderma viride for fungal disease suppression. Refill the pit with this mixture, mounding it slightly above ground level to account for settling after watering.

d). Planting Method

To plant the sapling, start by digging a hole at the center of the prepared pit that’s slightly larger than the root ball. Gently remove the sapling from its container, being careful not to disturb the roots, and loosen any roots that are tightly wound.

Place the sapling into the hole, ensuring the root collar sits at or just above the soil surface—never plant it deeper than it was in the nursery. Fill the hole with the native soil, pressing it lightly around the roots to remove air pockets. Create a shallow basin roughly 1 meter wide around the base to help retain water, and water the sapling thoroughly right after planting.

Support young plants by staking them securely to prevent wind damage. Lastly, spread a thick layer of organic mulch—such as straw, wood chips, or dried leaves—within the basin, making sure to leave a 10–15 cm gap around the trunk to retain moisture and reduce weed growth.

e). Number of Plants per Acre

With a spacing of 10 meters by 10 meters, approximately 40 plants can be accommodated per acre.

Intercropping

Intercropping with tamarind is highly feasible and strongly recommended, particularly during the first 8–10 years when trees are still young and their canopies allow ample sunlight. The light shade provided by tamarind can even benefit certain crops in hot climates.

Intercropping offers multiple advantages, including early income generation, efficient space utilization, weed suppression, soil fertility improvement—especially with nitrogen-fixing legumes—and reduced soil erosion.

Suitable intercrops include legumes like pigeon pea, cowpea, green gram, black gram, and groundnut; cereals such as sorghum and millets; oilseeds like sesame and safflower; and shade-tolerant vegetables such as taro, ginger, turmeric, chilies, eggplant, and cucurbits. In cooler subtropical areas, pulses like chickpea and lentil are also appropriate choices.

Irrigation

Irrigation is crucial during the establishment phase (first 2–3 years), with regular watering every 7–10 days during dry periods to ensure survival and promote deep rooting. Once mature, tamarind trees become highly drought-tolerant due to their deep root systems and may not require irrigation in regions with reliable monsoons.

However, supplemental irrigation greatly enhances yield and fruit quality, especially during prolonged dry spells and critical stages like flowering and fruit development (February to June in the Northern Hemisphere), when water stress can lead to significant flower and fruit drop.

Common irrigation methods include basin irrigation around individual trees and drip irrigation, which is efficient, conserves water, and supports fertigation—ideal for dry areas or critical growth phases. Overwatering and waterlogging must be avoided, as tamarind roots are prone to rot; soil should be allowed to partially dry between waterings, with deep, infrequent irrigation preferred over light, frequent watering.

Fertilizer and Manure

For accurate fertilizer application, always follow the recommendations based on the most recent soil test report. However, in the absence of one, a general fertilizer dose can be used. Apply fertilizers and manure evenly in a ring around the trunk, then either incorporate them lightly into the soil or water them in to ensure proper absorption.

Young Trees (Years 1-4)

| Aspect | Details |

| Focus | Vegetative growth |

| Fertilizer Type | Balanced NPK (e.g., 15-15-15, 16-16-16) |

| Application Rate | Start: 100g/tree/application. Year 4: 300–400g/tree/year (total annual) |

| Organic Matter | 10–15 kg FYM/compost per tree/year (applied around drip line) |

| Application Schedule | Three split doses: 1. Mid-February to March 2. June to July 3. September to October |

Bearing Trees (Year 5+)

| Nutrient | Requirement | Application Details | Notes |

| Nitrogen (N) | 600g/tree/year | Split doses: • 50% September to October • 25% Mid Feb. to March • 25% June to July | Moderate requirement; excess promotes leafy growth. |

| Phosphorus (P) | 400g P₂O₅/tree/year | Apply full dose in September to October | Critical for root development, flowering, and fruiting. |

| Potassium (K) | 600g K₂O/tree/year | Split doses: • 50% September to October • 25% Mid Feb. to March • 25% June to July | Vital for fruit quality, development, and disease resistance. |

| Organic Matter | 20–30 kg FYM/tree/year | Split doses: • 50% September to October • 25% Mid Feb. to March • 25% June to July | Essential for soil health. |

| Micronutrients | Borax (0.1–0.2%) & ZnSO₄ (0.3%) | Foliar sprays | Spray during flowering phase to increase fruit set |

Weed Control

Weed control is vital during the first 3–5 years, as young tamarind trees compete poorly with weeds. Mulching with 10–15 cm of organic material within the drip line helps suppress weeds, retain moisture, and improve soil health. Shallow hoeing, manual weeding, and cover crops like clover or perennial peanut can also be effective.

Use herbicides cautiously: apply Diuron (1–2 kg/ha) or Oxyfluorfen (0.5–1.0 kg/ha) as pre-emergents on weed-free soil, avoiding the trunk, and Glyphosate (1–2% solution) only as a directed spray outside the drip line. Avoid herbicide use under the canopy.

Flowering and Fruit Management

Flowering

Tamarind trees typically flower in spring (February to April in the Northern Hemisphere). The flowers are pale yellow to pinkish and appear in small racemes. They are primarily cross-pollinated by insects such as bees and flies. To protect pollinators, avoid using harmful insecticides during the blooming period.

Fruit Set and Development

Tamarind produces indehiscent pods (legumes), with some natural fruit drop occurring after setting. The pods develop gradually over several months and usually mature in the dry season, around 6–8 months after flowering.

Pruning

Pruning in young trees is essential for shaping, either into a strong central leader or an open vase structure with well-spaced scaffold branches. Mature trees require only minimal pruning to remove dead, diseased, damaged, or crossing branches. Thinning dense canopies improves light penetration and air circulation, helping reduce disease risk. Pruning should be done after harvest.

Thinning

Thinning is not commonly practiced in large tamarind trees due to their height and natural fruit drop. However, in younger trees or cultivars with heavy fruit clusters, selectively removing some pods can enhance the size and quality of the remaining fruits.

Propping

Propping is rarely necessary in tamarind cultivation but may be used if a branch is heavily loaded with fruit and at risk of breaking.

Pest and Disease Management

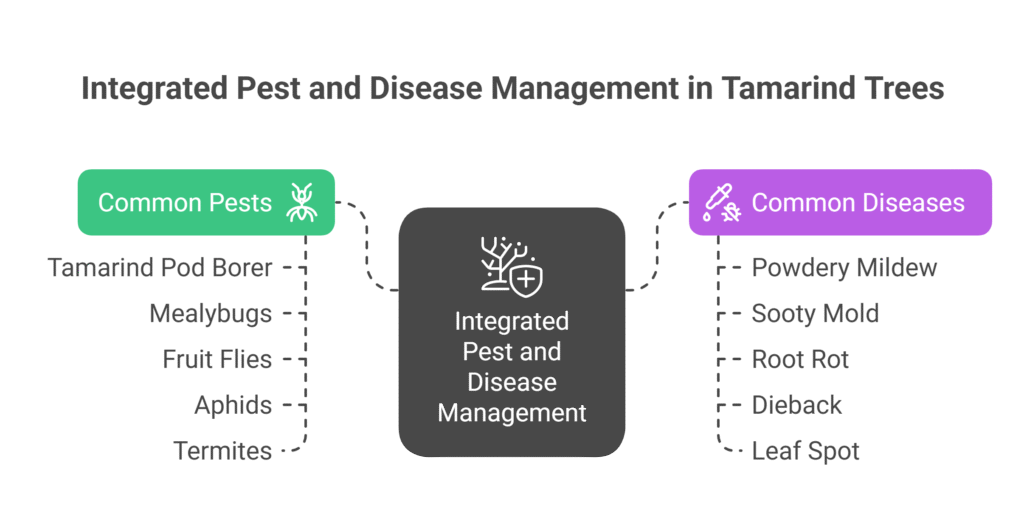

Common Pests

Tamarind Pod Borer (Cryptophlebia ombrodelta)

Larvae that dig into pods and harm the pulp makes this a serious pest. Using pheromone traps, promoting natural predators, and maintaining field sanitation by eliminating infected pods are all part of management. Apply Spinosad 45% SC as a targeted spray at a rate of 0.3 ml per liter of water in cases of severe infestation.

Mealybugs

Mealybugs produce honeydew and suck sap from leaves and pods, which encourages the spread of sooty mold. Use insecticidal soap (2–3 ml/L), horticultural oil (2–3 ml/L), or powerful water sprays to control them. Control can be improved by introducing beneficial insects like lacewings and ladybugs. Additionally, keep ants under control near the base of the tree since they shield mealybugs from predators.

Fruit Flies

Fruit flies may infest ripening or damaged pods. Effective control includes collecting and destroying fallen or overripe pods, using methyl eugenol-based traps (10 traps/ha), and applying protein bait sprays prepared with malathion 50% EC at 2 ml/L mixed with protein hydrolysate at 1% concentration during the fruit development stage.

Aphids

Aphids feed on plant sap, causing curling of new leaves and may transmit viral diseases. They are usually controlled by natural predators like lady beetles, but in case of heavy infestation, use insecticidal soap (2–3 ml/L) or imidacloprid 17.8% SL at 0.3 ml/L as a foliar spray during early infestation.

Termites

Termites can damage young tamarind trees, especially under dry conditions. Preventive measures include applying neem cake at 250–500 g per plant around the base during planting. For active infestations, apply a soil drench of chlorpyrifos 20% EC at 2 ml per liter of water around the base of the tree to kill termites in the root zone.

Common Diseases

a). Powdery Mildew

Powdery mildew grows best in warm, humid environments and forms a white, powdery coating on leaves, young shoots, and flowers. Flower drop, leaf curling, and yellowing are early indicators. One organic preventive measure is to use neem oil at 5 ml per liter or to spray wettable sulfur at 2 g per liter of water. If the infection is severe, use a systemic fungicide such as Hexaconazole 5% EC at 1 ml per liter or Triadimefon 25% WP at 0.5 g per liter, repeating as necessary at 10- to 15-day intervals.

b). Sooty Mold

Aphids, mealybugs, and scales are among the sap-sucking insects that produce honeydew, which is where sooty mold, a black, velvety fungal growth, develops on leaves and stems. Although it doesn’t hurt the plant directly, it inhibits photosynthesis and blocks sunlight. Horticultural oils, insecticidal soap (2–3 ml/L), or systemic insecticides such as imidacloprid 17.8% SL at 0.3 ml/L are effective methods for controlling insect pests. The mold typically dries and falls off after the bug population is under control.

c). Root Rot (Phytophthora, Fusarium)

Trees in soil that is either wet or poorly drained are susceptible to the dangerous disease known as root rot (Phytophthora, Fusarium). Yellowing, wilting, stunted growth, and dieback are some of the symptoms. The best approach is prevention by preventing overwatering and ensuring adequate drainage. For early-stage infections, apply a soil drench around the root zone using either Metalaxyl 35% WS at 1.25 g per liter or Fosetyl-Al (Aliette) 80% WP at 2-3 g per liter. Severity may require several applications.

d). Dieback

Dieback is caused by fungal pathogens such as Botryodiplodia, leading to the drying of twigs and branches from the tips. Control involves pruning infected branches well below the visibly affected area, followed by disinfection of tools using 1% bleach or 70% alcohol. After pruning, apply a wound dressing or a copper-based fungicide paste to cut surfaces. Keeping trees healthy with balanced fertilization and proper irrigation also reduces risk.

e). Leaf Spot

Small brown or black dots on leaves are the result of leaf spot infections, which are brought on by several fungus. They hardly ever need chemical treatment and are typically cosmetic. Pruning carefully will increase air circulation, and removing and discarding fallen leaves will stop the spread of spores. Apply Mancozeb 75% WP at 2 g per liter or Chlorothalonil 75% WP at 2 g per liter as a protective spray if outbreaks are severe; repeat every 10–14 days if necessary.

Harvesting

Maturity Indicators – Ripe Pods

For pulp use, tamarind pods should be harvested when fully mature. Indicators include a brittle outer shell that turns brown or cinnamon-colored, and a brown to reddish-brown pulp that is soft, sticky, and separates easily from the shell and fibers. Sweet varieties will have a sweet-sour taste. This is the most common harvest stage for fresh pulp consumption or processing.

Maturity Indicators – Immature Pods (Vegetable Use):

For fresh or vegetable use, pods are harvested much earlier, typically 3–4 months after flowering. These pods are green, tender, and filled with acidic, unripe pulp. They are preferred in culinary applications for their tangy flavor.

Harvesting Method – Mature Pods

Use long poles with hooks or cutters to detach pod clusters from the branches. In tall trees, skilled harvesters may climb to access higher pods. Avoid shaking branches, as mature pods are brittle and may shatter. Collect fallen pods daily to avoid spoilage or damage.

Harvesting Method – Immature Pods

Immature pods are hand-picked carefully to avoid damage. Harvesting at this stage requires a more delicate approach due to the tenderness of the pods.

Handling

Handle both mature and immature pods gently to prevent bruising or cracking. Place them in baskets or crates without overfilling to maintain quality during transport and storage.

Post-Harvest – Drying for Storage or Processing:

For pulp storage, spread ripe pods in a thin layer on clean surfaces like mats or concrete floors and dry them under the sun for 5–10 days until the shells become brittle. Turn the pods regularly for uniform drying. Once dried, the pulp can be separated easily and stored or processed.

Post-Harvest – Fresh Use:

Immature pods should be used soon after harvest. Fully ripe pods can be stored fresh for a few weeks in cool, dry conditions. For long-term storage, dried pulp can be kept in airtight containers for several years without significant loss of quality.

Yield

Tamarind yield starts low in young trees (5–10 years), ranging from 5 to 20 kg per tree, and increases gradually as trees mature. By 15 years and beyond, trees reach their peak bearing stage, typically producing 150 to 300 kg of pods per tree annually under good conditions. With 40 trees per acre and an average yield of 200 kg per tree, the total yield can reach approximately 8,000 kg or 8 tonnes per acre.

Tamarind trees may show mild biennial bearing, where yield fluctuates between years, though it is less pronounced compared to some other fruit crops. With proper management practices such as balanced fertilization, pest and disease control, pruning, and timely harvesting, more consistent annual yields can be achieved.

Cost of Investment per Acre for Tamarind Farming

| S.N. | Cost Category | Amount (NRs.) |

| 1 | Land Preparation (Plowing) | 15,000 |

| 2 | Plant Saplings (40 × NRs.300) | 12,000 |

| 3 | Pit Digging | 4,000 |

| 4 | Planting | 2,000 |

| 5 | Fertilizers and Manure | 10,000 |

| 6 | Irrigation | 15,000 |

| 7 | Weed Control (Pre & Post-Emergence) | 5,000 |

| 8 | Pest & Disease Control | 7,000 |

| 9 | Miscellaneous Costs | 7,000 |

| Total Initial Cost (Year 1) | 77,000 |

Annual maintenance cost per acre for Tamarind Farming

From the 2nd year onward, the annual maintenance cost for tamarind farming is estimated at NRs. 75,000 per acre. This includes expenses for irrigation, fertilization, pruning, pest and disease control, weed management, and general upkeep of the orchard. These recurring costs remain relatively consistent each year from year 2 through year 50, ensuring healthy tree growth and sustained productivity.

Income from Tamarind Farming Per Acre

| Year | Yield/Tree (kg) | Yield/Acre (kg) | Price (NRs/kg) | Income/Acre (NRs) |

| 5th Year | 5 | 200 | 60 | 12,000 |

| 6th Year | 10 | 400 | 60 | 24,000 |

| 7th Year | 15 | 600 | 60 | 36,000 |

| 8th Year | 20 | 800 | 60 | 48,000 |

| 9–14th Year | 80 | 3,200 | 60 | 192,000/year |

| 15–25th Year | 200 | 8,000 | 60 | 480,000/year |

| 26–40th Year | 150 | 6,000 | 70 | 420,000/year |

| 41–50th Year | 75 | 3,000 | 75 | 225,000/year |

Analysis of Tamarind Farming Profit Per Acre

In the first year of tamarind farming, the total investment cost is NRs. 77,000, with no income generated, resulting in a loss of NRs. 77,000. During years 2 to 4, the orchard incurs annual maintenance costs of NRs. 75,000, totaling NRs. 225,000, again with no income, leading to an additional loss of NRs. 225,000.

From years 5 to 8, the trees begin yielding produce, but returns remain below maintenance costs, with cumulative income of NRs. 120,000 and expenses of NRs. 300,000, resulting in a net loss of NRs. 180,000. Profitability begins in the commercial yield phase (years 9–14), generating NRs. 1,152,000 in income against NRs. 450,000 in costs, yielding a net profit of NRs. 702,000.

Peak profits occur from years 15–25, with NRs. 5,280,000 in income and NRs. 825,000 in costs, producing NRs. 4,455,000 in profit. The mature yield phase (years 26–40) brings in NRs. 6,300,000 income with NRs. 1,125,000 in expenses, yielding a profit of NRs. 5,175,000. In the late yield phase (years 41–50), the orchard earns NRs. 2,250,000 and incurs NRs. 750,000 in costs, resulting in NRs. 1,500,000 profit.

Sources

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

University of California Agriculture & Natural Resources (UC ANR)

Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC)

Punjab Agricultural University (PAU)

Tamil Nadu Agriculture University (TNAU) – Agritech portal

Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR)

Congratulations croplibrary for availing such comprehensive information on the agronomy and profitability of different crops. Thank you and be blessed