Potato Bacterial Wilt

Potato bacterial wilt is a serious and highly destructive vascular disease that severely affects potato cultivation worldwide. The disease targets the water-conducting tissues of the plant, resulting in sudden and irreversible wilting even when adequate soil moisture is available.

It is widely prevalent in tropical, subtropical, and warm temperate regions and represents a major threat to potato production due to its rapid spread, broad host range, and ability to survive for long periods in soil, infected seed tubers, irrigation water, and weed hosts.

In the absence of any effective curative treatment, potato bacterial wilt remains one of the most challenging diseases to manage, necessitating strict preventive measures and an integrated disease management approach.

Cause

Potato bacterial wilt is caused by the soil- and seed-borne bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum. It is a highly destructive pathogen with a wide host range, infecting solanaceous crops such as potato, tomato, eggplant, chili, and tobacco. The bacterium survives in infected seed tubers, plant debris, soil, irrigation water, and alternate weed hosts, making the disease difficult to eradicate once established.

Symptoms

The early symptoms of potato bacterial wilt appear as sudden wilting of the upper leaves during the hottest part of the day, with plants often showing partial recovery during cooler night hours. As the infection advances, the wilting becomes permanent and is not accompanied by leaf yellowing, which helps distinguish the disease from nutrient deficiencies or drought stress.

On cutting infected stems or tubers, a characteristic brown discoloration of the vascular tissues can be clearly observed. When these cut portions are immersed in clean water, a milky white bacterial ooze streams out from the vascular bundles, serving as a key diagnostic sign of the disease. In severe or advanced stages, infected tubers undergo internal rotting, produce a foul odor, and may become vulnerable to secondary microbial infections, leading to complete tuber decay.

Epidemiology

Potato bacterial wilt is most prevalent and severe in warm, humid environments, where temperatures between 25–35 °C provide optimal conditions for the growth and multiplication of the pathogen. High soil moisture levels, especially in poorly drained fields, facilitate bacterial survival, movement, and rapid spread within the soil profile.

The disease is primarily disseminated through infected seed tubers, contaminated irrigation water, farm implements, infested soil, and alternate weed hosts, allowing the pathogen to persist and spread across fields and seasons. Continuous or repeated cultivation of susceptible host crops further increases disease incidence by building up the bacterial population in the soil.

Infection occurs when the bacterium enters the plant through wounds caused by cultivation practices, natural openings, or actively growing root tips, from where it colonizes the vascular system and initiates disease development.

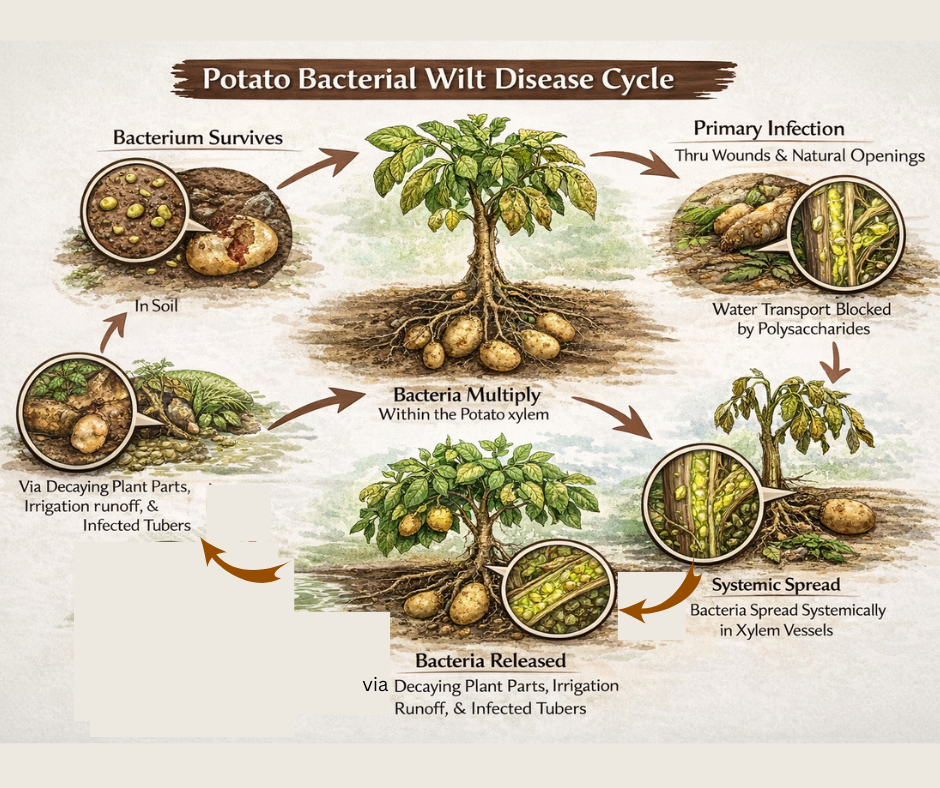

Disease Cycle of Potato Bacterial Wilt

The disease cycle of potato bacterial wilt begins with the survival of the pathogen in soil, infected seed tubers, crop residues, irrigation water, and alternative weed hosts during the off-season. Primary infection occurs when the bacterium enters potato plants through wounds created during cultivation, natural openings, or actively growing root tips.

Once inside the plant, the pathogen rapidly colonizes the xylem vessels, where it multiplies extensively and produces large amounts of extracellular polysaccharides. These substances obstruct the vascular tissues, disrupt water movement, and ultimately cause characteristic wilting symptoms.

As the disease progresses, the bacterium spreads systemically throughout the plant and is released back into the environment through decaying plant tissues, infected tubers, and irrigation runoff, thereby contaminating the soil and water sources and perpetuating the disease cycle in subsequent cropping seasons.

Management Practices

An integrated disease management approach is essential for effective control.

a). Seed and Planting Material Management

- Use certified, disease-free seed tubers only; never plant seed from wilt-affected fields.

- Before planting, inspect seed tubers and discard any showing vascular browning or ooze.

- Treat seed tubers with hot water at 50–55°C for 20–30 minutes to reduce surface bacterial contamination.

- Apply biocontrol agents (Pseudomonas fluorescens or Bacillus subtilis) as seed treatment @10 g/kg seed (as per product recommendation).

b). Field Selection and Preparation

- Avoid planting potatoes in fields with a history of bacterial wilt.

- Select well-drained soils; avoid low-lying or waterlogged areas.

- Practice deep ploughing and soil solarization during summer to reduce soil inoculum.

- Improve drainage channels to prevent standing water and pathogen movement.

c). Crop Rotation

Follow crop rotation for at least 2–3 years with non-host crops such as:

- Cereals (maize, wheat, rice)

- Legumes (beans, peas)

Avoid rotation with solanaceous crops like tomato, brinjal, chili, and tobacco.

d). Field Sanitation and Hygiene

- Rogue out and destroy infected plants immediately along with surrounding soil.

- Disinfect farm tools and implements using 1% bleaching powder or sodium hypochlorite solution.

- Control weed hosts that can harbor the pathogen.

- Prevent movement of contaminated soil between fields.

e). Soil and Water Management

- Avoid excessive irrigation; adopt light but frequent irrigation.

- Do not use contaminated irrigation water from infected fields.

- Apply lime or bleaching powder (10–15 kg/ha) in heavily infested soils to reduce bacterial population.

f). Biological Control and Soil Health Improvement

- Apply Trichoderma spp. or Pseudomonas fluorescens to soil @ 2.5–5 kg/ha mixed with FYM or compost.

- Incorporate well-decomposed farmyard manure or compost to enhance beneficial microbial activity.

- Use green manuring crops to improve soil suppressiveness.

g). Resistant / Tolerant Varieties

- Grow bacterial wilt-tolerant potato varieties recommended for your region.

- Avoid repeated cultivation of susceptible varieties.

h). Chemical Control (Limited Role)

- Chemical bactericides are not effective once infection occurs due to systemic colonization.

- Chemicals may only be used for soil sanitation, not plant cure.

FAQs

Q1. Can you save a plant with bacterial wilt?

Once a potato plant is infected with bacterial wilt, it cannot be saved or cured, because the causal bacterium blocks the plant’s vascular system and spreads systemically throughout the tissues. No chemical or biological treatment can eliminate the pathogen from an already infected plant.

In practical field conditions, the best action is to immediately remove and destroy infected plants along with surrounding soil to prevent further spread to healthy plants. Management should therefore focus on prevention, including the use of disease-free seed tubers, proper field drainage, crop rotation with non-host crops, strict field sanitation, and the use of biocontrol agents to reduce soil inoculum. Early detection and prompt removal of affected plants are critical to minimizing yield losses and protecting the remaining crop.

Q2. What is the chemical treatment for bacterial wilt?

There is no effective chemical treatment for bacterial wilt once a potato plant is infected, because the bacterium (Ralstonia solanacearum) colonizes the plant’s vascular system and cannot be eliminated by foliar sprays or soil-applied chemicals.

In practice, chemical measures are only used for preventive purposes, such as soil sanitation in heavily infested fields, where compounds like bleaching powder or lime can help reduce bacterial populations in the soil before planting.

Farmers should focus on using disease-free seed tubers, improving drainage, practicing crop rotation, and maintaining field hygiene, as these strategies are far more effective than chemicals in managing bacterial wilt and preventing its spread.

Q3. What plants are not affected by bacterial wilt?

Bacterial wilt, caused by Ralstonia solanacearum, primarily affects solanaceous crops such as potato, tomato, eggplant, chili, and tobacco. However, many non-solanaceous plants and cereals are not susceptible to this disease.

Crops like maize, wheat, rice, legumes (beans, peas), and certain grasses generally do not host the bacterium and can be safely included in crop rotation programs to reduce soil inoculum. These non-host plants help break the disease cycle, improve soil health, and are a practical strategy for managing bacterial wilt in fields prone to infection.

Sources

University of California Agriculture & Natural Resources (UC ANR)

European Plant Protection Organization (EPPO)

Tamil Nadu Agriculture University (TNAU) – Agritech portal

Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR)

Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC)

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development (Nepal)