Mulberry Farming

Mulberry (Morus spp.) is primarily cultivated for its leaves, which are the exclusive food source for silkworms (Bombyx mori) in sericulture (silk production). It can also be grown for its fruit. Mulberry farming profit per acre can be a rewarding long-term venture, yielding steady returns once the crop is established.

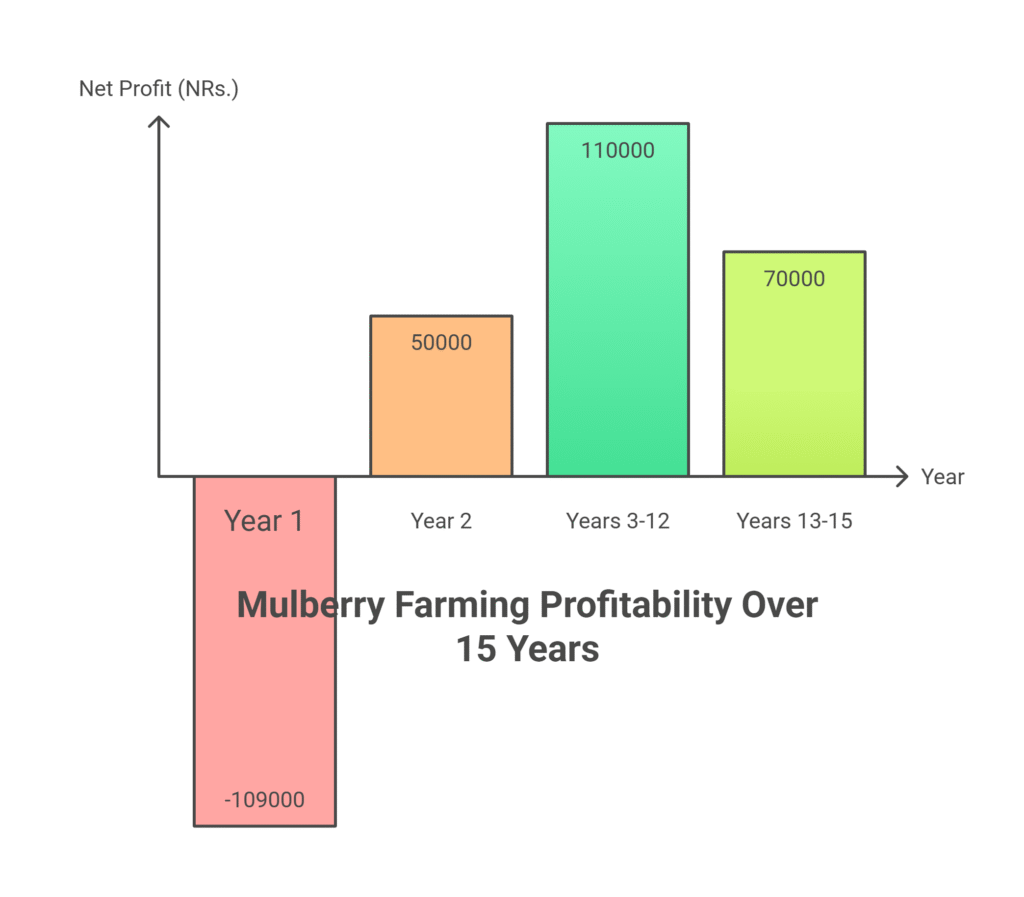

Over a 15-year cycle, one acre of mulberry generates a total income of NRs. 2,090,000 against total costs of NRs. 839,000, resulting in a net profit of NRs. 1,251,000 and an overall return on investment (ROI) of about 149%. While the first year shows a loss of NRs. 109,000 due to high establishment expenses, profitability begins in Year 2 with net earnings of NRs. 50,000.

The peak production phase in Years 3–12 delivers NRs. 110,000 annually, contributing significantly to total profits, and even during the declining yield phase in Years 13–15, the farm maintains NRs. 70,000 per year. On average, mulberry farming can return about NRs. 89,357 in net profit annually from the second year onward, making it a sustainable and moderately high-return agricultural enterprise.

Land Preparation

Land preparation involves several critical steps to ready the field for cultivation. It begins with initial clearing, where existing vegetation, stumps, rocks, and debris are removed to provide a clean working area.

This is followed by deep ploughing using a mouldboard plough to a depth of 30–45 cm, which breaks hardpans, improves aeration, incorporates organic matter, and exposes soil pests and pathogens to sunlight. Next is harrowing, where disc harrows or rotavators break down large soil clods, level the field, and produce a fine tilth suitable for sowing.

In sloping areas, contour bunds or basins are formed to prevent soil erosion and enhance water conservation. Finally, organic matter such as well-rotted farmyard manure or compost (15–20 tonnes per hectare) is applied during the last harrowing and thoroughly mixed into the soil to enrich fertility and structure.

Soil Type

Deep, well-drained, fertile loamy soil with a high water-holding capacity is the best kind of soil for cultivation, while red, sandy, and clay loamy soils can all be used with the right amendments. Liming should be used to correct highly acidic soils (pH <5.5), but the crop can withstand a broad pH range from 6.2 to 7.8, with best growth occurring close to neutral pH (6.5–7.0).

A minimum of two to three feet is required to support substantial root development, and proper drainage is essential because soggy conditions can cause root rot and limit plant growth. Despite the crop’s considerable resistance to salinity and alkalinity, growth and yield can be severely hampered by extremely saline or sodic soils.

Climatic Requirements

Optimal climatic conditions for cultivation include temperatures between 24°C and 28°C, though the crop tolerates a broader range from 15°C to 38°C; growth becomes dormant below 12°C, and frost can damage young shoots and leaves, while extreme heat above 38°C may stress the plants.

Annual rainfall between 600–2500 mm, well-distributed throughout the year, supports healthy growth, but supplemental irrigation is essential during dry spells to maintain consistent leaf production, and waterlogging must be avoided. Full sunlight is crucial for maximizing photosynthesis and leaf yield, as shade negatively impacts growth and leaf quality.

Moderate to high humidity levels (65–80%) enhance leaf succulence and are beneficial for silkworm rearing. Additionally, strong winds can harm young plants, making the use of windbreaks advisable in exposed areas

Major Cultivars

| Cultivar Name | Key Characteristics | Common Varieties | Primary Use / Notes |

| Morus alba (White Mulberry) | Most widely used globally for sericulture; high leaf yield, good quality, adaptable | S-1, S-13, S-34, S-54, V1, Kanva-2, MR2, Thai varieties | Primary cultivar for sericulture (silkworm rearing) |

| Morus indica (Indian Mulberry) | Adapted specifically to Indian subcontinent conditions | S-36, S-1635, K2, Mandalay | Grown primarily in the Indian subcontinent for sericulture |

| Morus nigra (Black Mulberry) | Produces large, flavourful fruit; leaves less preferred by silkworms | (Often not specified by variety for sericulture) | Primarily grown for fruit production; less suitable for silkworms |

| Morus rubra (Red Mulberry) | Native to North America | (Varieties often regionally specific) | Used for fruit and wildlife habitat; native to North America |

| Hybrids | High-yielding varieties developed for specific traits | Victory-1, G4 (examples) | Developed for improved yield and performance; many types available |

Seed rate per acre

Mulberry is propagated primarily through vegetative methods such as cuttings, grafts, or buddings, as this ensures true-to-type plants with uniform characteristics and faster establishment compared to seed propagation.

For planting with saplings or tissue culture plants, around 5,000 plants per acre are required, following the standard bush system spacing (90 cm × 90 cm), which supports uniform growth, ease of management, and optimal leaf yield essential for sericulture.

Planting

Planting Season

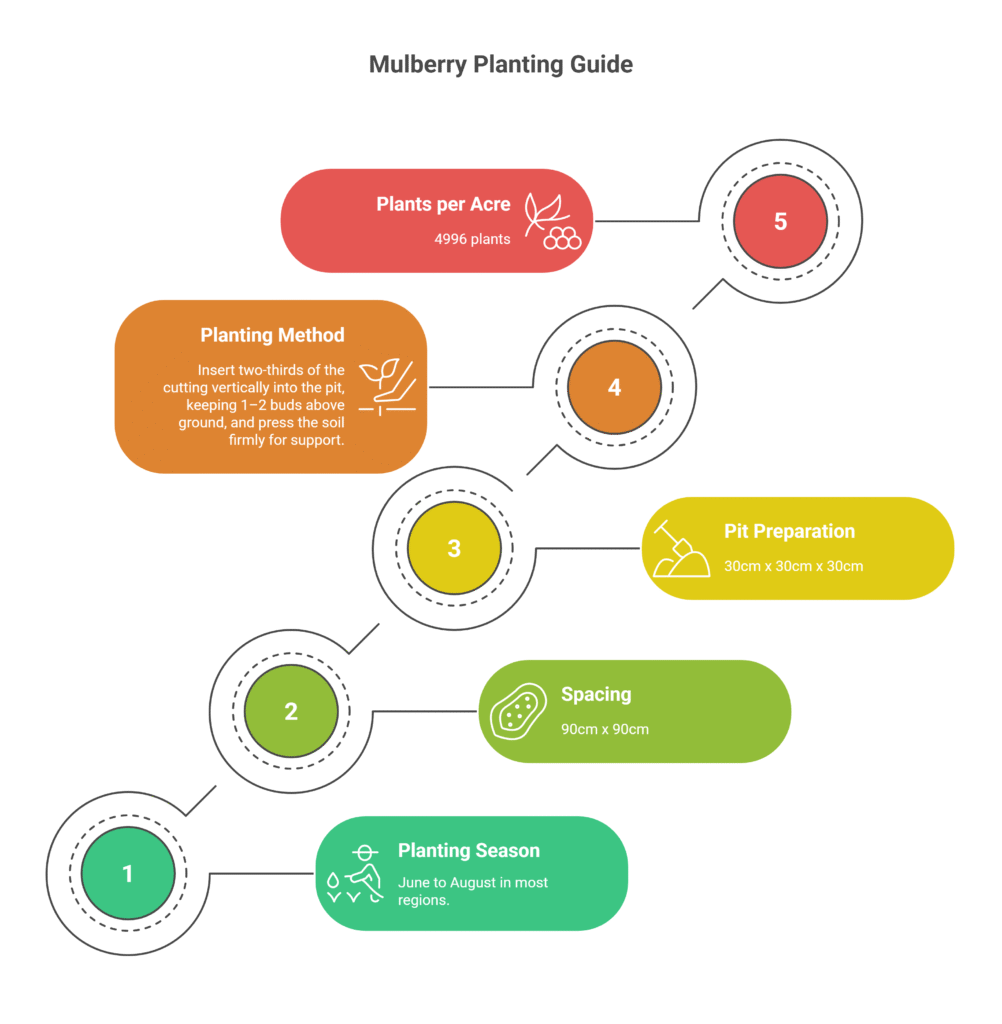

The optimal planting season is during the monsoon months (June to August in most regions) when soil moisture is naturally abundant, promoting better establishment and early growth. Alternatively, planting can also be done in early spring (February to March), provided there is assured irrigation to support initial development. However, extreme heat or cold conditions should be avoided to prevent stress and poor plant performance.

Spacing

The bush system, the most common planting method for sericulture, involves spacing plants at 90 cm between rows and 90 cm between plants. This layout ensures adequate sunlight penetration, air circulation, and ease of maintenance, while supporting optimal leaf production crucial for silkworm rearing.

Pit Preparation

Pit preparation should be done 1–2 months before the planting season to ensure readiness and soil conditioning. Each pit should be dug to a size of 30 cm x 30 cm x 30 cm (length, width, and depth). For refilling, mix the excavated topsoil with 5–10 kg of well-rotted farmyard manure or compost, 100 g of superphosphate, 50 g of muriate of potash (MOP), and 50 g of Trichoderma viride per pit.

The pit should be refilled with this enriched mixture, mounded slightly above ground level to accommodate settling. If the pits are filled well before planting, light watering is recommended to maintain moisture and encourage microbial activity.

Planting Method

The planting method varies based on the planting material used. For cuttings, insert two-thirds of the cutting length vertically into the center of the prepared pit, ensuring that 1–2 buds remain above ground, and firmly press the soil around it to provide support.

For saplings or tissue culture plants, carefully remove the polybag without disturbing the root ball, place the plant in the center of the pit at the same depth as it was in the nursery, fill the pit with soil, gently firm it around the roots, and water immediately to ensure proper establishment.

Number of Plants per Acre

In the bush system with a spacing of 90 cm by 90 cm, approximately 4,996 plants per acre can be planted, providing an optimal density for healthy growth and maximum leaf yield in mulberry cultivation.

Intercropping

Intercropping with mulberry is feasible only during the initial 1–2 years before the mulberry canopy closes, allowing light and space for other crops to grow. Suitable intercrops are low-growing, non-climbing, shallow-rooted, and short-duration crops that do not compete heavily for nutrients or water and do not harbor major mulberry pests or diseases; common examples include legumes such as beans, peas, and groundnut, leafy vegetables like spinach and lettuce, as well as garlic, onion, turmeric, and ginger.

Tall crops like maize and sorghum, climbing vines, deep-rooted plants, or those attracting common pests should be avoided. Proper management involves maintaining adequate spacing for both mulberry and intercrops, applying separate fertilizers or manure for the intercrop, and discontinuing intercropping once mulberry bushes are well-established and regular leaf harvesting begins.

Irrigation

Importance of Consistent Moisture

Maintaining consistent soil moisture is absolutely critical for successful mulberry cultivation. This ensures continuous, high-quality leaf production throughout the growing season. Adequate irrigation becomes especially vital during extended dry periods and immediately following major operations like pruning or heavy leaf harvesting, as these events stress the plants and require sufficient water for rapid regrowth.

Irrigation Frequency

The frequency of irrigation depends significantly on soil type, prevailing climate, and the season. As a general guideline, mulberry fields typically require watering every 7 to 12 days during the hot summer months to combat high evaporation. In the cooler winter season, irrigation can be reduced to intervals of 15 to 20 days. During the monsoon season, irrigation is generally unnecessary unless there are prolonged breaks in the rainfall.

Recommended Irrigation Methods

Several irrigation methods can be employed, each suited to different planting systems:

- Basin/Ring Method: This common technique involves creating individual watering basins around the base of each mulberry plant.

- Furrow Irrigation: This method is suitable for mulberry bushes planted in rows, where water flows along channels (furrows) between the rows.

- Drip Irrigation (Highly Recommended): Drip irrigation is the most efficient and preferred method. It saves substantial amounts of water (30-50% compared to traditional methods), reduces weed growth by minimizing surface moisture, delivers water and dissolved nutrients directly to the root zone, and helps maintain optimal, consistent soil moisture levels. The system should be designed with laterals placed along the rows and emitters positioned at each plant.

Annual Water Requirement

Mulberry cultivation requires a significant amount of water annually. The total water requirement is approximately 40 to 50 hectare-centimeters (ha-cm) per year. It’s important to note that this figure can vary based on the specific local climate conditions and the irrigation system used, with drip systems typically requiring less total water than surface methods to achieve the same results.

Fertilizer and Manure

For accurate fertilizer application, it is essential to follow the recommendations based on a soil test report.

| Type | Material | Annual Rate per Acre | Splitting Strategy | Timing | Application Method |

| Organic | Well-rotted FYM or Compost | 10-15 tonnes | 2 splits | Before monsoon + winter | Incorporate into soil during inter-cultivation |

| Nitrogen (N) | Urea | 100-150 kg (N) (equivalent to 220-330 kg urea) | 4 split doses | Mid-February; May; August, and November | Broadcast evenly in root zone + light incorporation + irrigation Drip fertigation highly efficient |

| Phosphorus (P) | Superphosphate/DAP | 50-75 kg (P₂O₅) (equivalent to 300-450 kg superphosphate or 110-165 kg DAP) | 2 splits | Pre-monsoon + post-monsoon | Broadcast evenly in root zone + light incorporation + irrigation Drip fertigation highly efficient |

| Potassium (K) | MOP (Muriate of Potash) | 40-60 kg (K₂O) (equivalent to 65-100 kg MOP) | 2 splits | Pre-monsoon + post-monsoon | Broadcast evenly in root zone + light incorporation + irrigation Drip fertigation highly efficient |

Weed Control

In mulberry farming, weed control is crucial because weeds fiercely compete for sunshine, nutrients, and water, which significantly lowers leaf output. Both mechanical and cultural techniques, such as routine hand weeding or hoeing, are important for managing weeds, particularly in areas with strong weed pressure near young plants.

In addition to keeping the soil moist, mulching with organic materials like dried leaves or paddy straw can also inhibit the growth of weeds.

Herbicides used for chemical control should be used carefully; pre-emergence herbicides, such as Pendimethalin, can be sprayed after pruning but before weeds appear, as long as the label is properly followed and no mulberry foliage comes into touch with the herbicide. However, because of the possibility of toxicity to silkworms, post-emergence herbicides are typically avoided in sericulture.

Inter culture operation

Training

Training involves shaping young mulberry plants to develop the desired growth framework, whether as a bush or a tree. In the commonly used bush system, training is done by pinching the main stem early to encourage the development of 3 to 5 main shoots from the base, resulting in a well-structured plant that supports optimal leaf production and ease of harvesting.

Pruning

Pruning plays a vital role in mulberry cultivation, helping to boost leaf yield and ensure overall plant vigor. It serves several key functions, such as removing old or non-productive branches, keeping plant height manageable, promoting the growth of fresh, tender shoots ideal for feeding silkworms, enhancing light penetration, and supporting pest and disease control.

The three main pruning methods include bottom pruning, where shoots are cut back to 15–30 cm above the ground multiple times annually to stimulate strong regrowth; middle pruning, which involves trimming shoots to 70–90 cm above ground level, usually done once a year after winter; and leaf harvest pruning, where leaves are collected along with tender shoots during rearing seasons.

Pruning is best carried out during plant dormancy—typically in winter or just before a new silkworm rearing cycle—using clean, sharp tools to reduce the risk of spreading diseases.

Flowering and Fruit Management

Mulberry can be either monoecious or dioecious, with flowers typically appearing in spring in the form of catkins. In sericulture-focused cultivation, flowering and fruiting are discouraged because they divert the plant’s energy away from leaf production, which is critical for silkworm rearing.

Regular pruning naturally helps suppress flower bud formation, and the timing of nitrogen application can also influence the extent of flowering. In contrast, for fruit production, different cultivars such as Morus nigra, Morus rubra, or fruiting hybrids are used, and specific pruning and training techniques are applied to promote the growth of flowering and fruiting wood. Fruits usually ripen in late spring to summer, and bird netting is often required to protect the harvest.

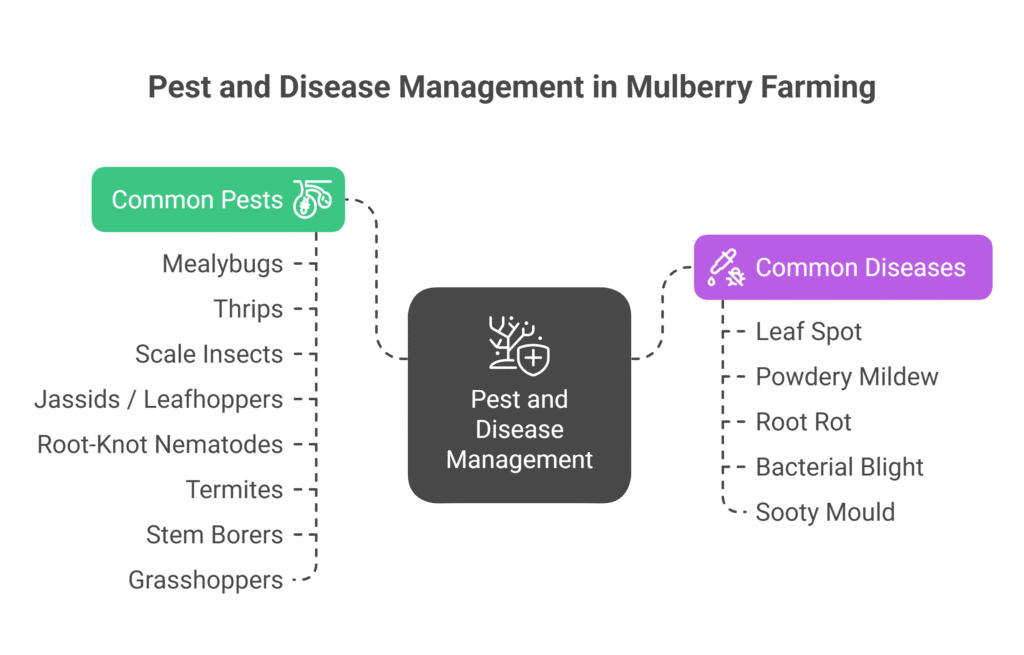

Pest and Disease Management

Common Pests

a). Mealybugs

Mealybugs are small, soft-bodied insects with a cotton-like appearance that feed on mulberry plants by sucking sap, causing reduced vigor and excreting honeydew, which encourages sooty mold growth.

Control measures include systemic insecticides such as Imidacloprid 17.8% SL (0.5–1 ml/L as a soil drench or foliar spray), Thiamethoxam 25% WG (0.2–0.3 g/L), Buprofezin 25% SC (1–1.5 ml/L), or Chlorpyrifos 20% EC (2–2.5 ml/L as a foliar spray). Treatments may need repeating depending on the severity of infestation, and adding a wetting agent or sticker is advised to enhance coverage and effectiveness.

b). Thrips

Thrips are minute, slender pests that harm mulberry plants by scraping the surface and feeding on sap, resulting in silvery streaks, curled leaves, and deformed growth. Managing infestations effectively involves using insecticides such as Spinosad 45% SC (0.2–0.3 ml/L), Fipronil 5% SC (1.5–2 ml/L), Abamectin 1.8% EC (0.5–1 ml/L), Imidacloprid 17.8% SL (0.3–0.5 ml/L), or Cyantraniliprole 10% OD (0.75–1 ml/L).

It’s crucial to ensure complete spray coverage, particularly on the undersides of leaves and flower areas where thrips typically reside. To avoid the development of resistance, rotating insecticides with different modes of action is strongly recommended.

c). Scale Insects

Scale insects, either armored or soft-bodied, attach themselves to mulberry stems and leaves, sucking sap and gradually weakening the plant. Their protective covering makes control difficult, so targeting them during the vulnerable crawler stage is most effective.

Recommended treatments include a 1–2% horticultural oil solution combined with Buprofezin 25% SC (1–1.5 ml/L), Imidacloprid 17.8% SL (0.5–1 ml/L as a soil drench or systemic spray), or Chlorpyrifos 20% EC (2–2.5 ml/L). Horticultural oils are especially helpful as they suffocate the insects by coating their bodies, enhancing the overall effectiveness of the treatment.

d). Jassids / Leafhoppers

Jassids, also called leafhoppers, are agile, wedge-shaped insects that harm mulberry plants by extracting sap from the undersides of leaves, resulting in yellowing symptoms known as “hopper burn” and reduced plant growth.

Controlling these pests effectively requires the use of insecticides like Imidacloprid 17.8% SL (0.3–0.5 ml/L), Thiamethoxam 25% WG (0.1–0.2 g/L), Acetamiprid 20% SP (0.2–0.3 g/L), or Cypermethrin 25% EC (0.5–1 ml/L). For best results, sprays should be applied thoroughly to the underside of leaves where the insects feed.

e). Root-Knot Nematodes

Root-knot nematodes are microscopic worms that infect mulberry roots, causing the formation of distinctive galls or knots, which result in stunted growth and wilting of plants.

Effective management typically involves soil treatment using nematicides such as Carbofuran 3% CG (1–2 kg/acre, though it is highly restricted or banned in many areas), Cartap Hydrochloride 4% G (10–15 kg/acre), or biological agents like Paecilomyces lilacinus or Purpureocillium lilacinum following label instructions.

The use of fumigants such as Methyl Bromide is also highly restricted. Crop rotation and the application of bio-agents are essential strategies to control and reduce nematode populations sustainably.

f). Termites

Termites, highly social insects, consume cellulose found in wood, roots, and plant matter, leading to significant damage below ground or within plant stems.

Effective management involves soil treatments such as drenching or trenching using specific insecticides: Chlorpyrifos 20% EC (applied at 5 liters per hectare in 1000 liters of water), Imidacloprid 30.5% SC (used per label instructions, typically requiring higher concentrations for soil application), and Fipronil 5% SC (applied as a soil drench).

Applying these insecticides preventatively to the soil before planting offers the best protection. Additionally, any discovered termite mounds should be treated directly to halt infestation spread.

g). Stem Borers

Stem borers, the larvae of moths or beetles, tunnel into mulberry stems, disrupting the flow of water and nutrients, which leads to symptoms like dead hearts and wilting.

Effective control relies on early application of systemic insecticides such as Chlorantraniliprole 18.5% SC (0.3–0.4 ml/L), Flubendiamide 20% WG (0.25–0.5 g/L), Thiamethoxam 25% WG (0.2 g/L), or Carbofuran 3% CG (10–15 kg/acre at planting, though it is highly restricted or banned in many areas). It is essential to time treatments to target the young larvae before they bore into the stems for maximum effectiveness.

h). Grasshoppers

Grasshoppers are large, chewing insects that feed on leaves, stems, and flowers, leading to considerable defoliation.

Effective control involves using contact and stomach poison insecticides such as Lambda-cyhalothrin 5% EC (1–1.5 ml/L), Cypermethrin 25% EC (1–1.5 ml/L), Malathion 50% EC (2 ml/L), or Chlorpyrifos 20% EC (2–2.5 ml/L). Additionally, bait formulations like Carbaryl 5% bait can be useful. Management efforts are often most critical during the nymph (hopper) stage for better results.

Common Diseases

Leaf Spot (Cercospora, Pseudocercospora)

Leaf spot fungi cause brown/black lesions with yellow halos, leading to defoliation. Apply Chlorothalonil 75% WG (2-2.5 g/L water) or Mancozeb 75% WP (2-2.5 g/L) as protective sprays every 7-14 days. For systemic control, use Azoxystrobin 23% SC (1 ml/L) or Tebuconazole 25% EC (0.5-1 ml/L). Ensure thorough leaf coverage and rotate fungicide groups (FRAC codes) to prevent resistance. Remove infected debris first.

Powdery Mildew

This fungus forms white powdery patches on leaves/stems, causing distortion. Apply Wettable Sulfur 80% WP (3-4 g/L) or Potassium Bicarbonate (5 g/L) as contact fungicides. Systemic options include Myclobutanil 10% WP (0.5-1 g/L) or Tebuconazole 25% EC (0.5 ml/L). Spray at first sign of disease, covering all surfaces. Repeat every 10-14 days. Improve air circulation and avoid overhead watering.

Root Rot (Fusarium, Pythium)

Soil-borne pathogens cause wilting, yellowing, and blackened/mushy roots. For Pythium (water mold), drench soil with Metalaxyl-M 4% + Mancozeb 64% WP (2-2.5 g/L) or Mefenoxam 20% AS (1-1.5 ml/L). For Fusarium, use Carbendazim 50% WP (1 g/L) or Thiophanate-methyl 70% WP (1-1.5 g/L). Apply 100-200 ml solution per plant. Prevent with well-drained soil and avoid overwatering.

Bacterial Blight (Pseudomonas syringae)

Causes water-soaked spots turning brown/black with yellow halos. Use Copper Oxychloride 50% WP (2-2.5 g/L) or Streptomycin Sulphate 9% + Tetracycline 1% SP (0.5 g/L) as bactericides. Spray every 7-10 days during cool, wet periods. Combine with removing infected parts (sterilize tools with bleach). Copper-resistant strains may require Kasugamycin 3% SL (1-1.5 ml/L).

Sooty Mould

Black fungal growth coating leaves, fueled by honeydew from sap-sucking pests (aphids, scales). No direct fungicide needed – control the underlying insects with Imidacloprid 17.8% SL (0.3-0.5 ml/L) or Acephate 75% SP (1-1.5 g/L). Physically remove mould with a mild soap solution (5-10 ml dish soap/L water) sprayed vigorously. Improve plant hygiene to deter pests.

Harvesting

For Sericulture (Leaf Harvest)

In mulberry cultivation for sericulture, leaf harvesting typically begins 6–9 months after planting, with mature leaves collected every 60–90 days following pruning, depending on the climate and pruning frequency—allowing for 3–6 harvests annually.

Two main harvesting methods are used: leaf picking, which involves hand-plucking fully expanded, dark green, tender leaves and offers the highest quality but is labour-intensive; and branch cutting, where young succulent shoots (15–25 cm long) with leaves are cut and later stripped for feeding silkworms—commonly practiced in the bush system.

Harvesting is best done in the early morning or late evening to retain leaf moisture and freshness. It is important to avoid collecting wet, immature, or over-mature leaves, as these can spoil or reduce feed quality.

For Fruit

Harvest when fruits are fully colored, plump, and juicy. Handle gently to avoid bruising. Harvest multiple times as fruits ripen unevenly.

Yield

Leaf Yield (Sericulture)

Mulberry leaf production for silkworms is highly variable, influenced by cultivar choice, climate, soil quality, irrigation, pruning practices, and farm management. Initial yields in the first year are typically modest, ranging from 2,000 to 4,000 kg of fresh leaves per acre.

Once the bush system matures from the second year onward, yields increase significantly to between 15,000 and 35,000 kg per acre annually (equivalent to 35–80 tonnes per hectare). Since producing 1 kg of silkworm cocoons requires approximately 50–60 kg of fresh leaves, an annual yield of 30,000 kg leaves per acre can support the production of roughly 500–600 kg of cocoons.

Fruit Yield

Fruit yield in mulberry cultivation varies significantly depending on the cultivar and management practices. For fruiting varieties grown under favorable conditions, annual yields can range from 500 kg to over 5,000 kg per acre, with higher outputs achieved through proper care, pruning, irrigation, and nutrient management.

Cost of Investment per Acre for Mulberry Farming

| S.N. | Categories | Cost (NRs.) |

| 1 | Land Preparation (Plowing) | 15,000 |

| 2 | Plant Saplings | 30,000 |

| 3 | Pit Digging | 7,000 |

| 4 | Planting | 7,000 |

| 5 | Fertilizers & Manure | 35,000 |

| 6 | Irrigation | 20,000 |

| 7 | Weed Control (Pre & Post-emergence) | 7,000 |

| 8 | Pest & Disease Control | 8,000 |

| 9 | Miscellaneous Costs | 10,000 |

| Total Initial Cost (Year 1) | 139,000 |

Annual maintenance Cost per Acre

From the second year onward, mulberry farming requires an annual maintenance cost of approximately NRs. 50,000 per acre, which covers expenses such as fertilizers and manure, irrigation, weed management, pest and disease control, and other routine operational activities needed to sustain healthy plant growth and maintain consistent leaf yields.

Income from Per Acre Mulberry Farming

| Year | Leaf Yield (kg/acre) | Price (NRs./kg) | Total Income (NRs.) |

| 1 | 3,000 | 10 | 30,000 |

| 2 | 10,000 | 10 | 100,000 |

| 3 – 12 | 16,000 | 10 | 160,000 |

| 13 – 15 | 8,000 | 15 | 120,000 |

Analysis of Mulberry Farming Profit Per Acre

| Year | Income (NRs.) | Cost (NRs.) | Net Profit/Loss (NRs.) |

| 1 | 30,000 | 139,000 | –109,000 |

| 2 | 100,000 | 50,000 | 50,000 |

| 3 | 160,000 | 50,000 | 110,000 |

| 4 | 160,000 | 50,000 | 110,000 |

| 5 | 160,000 | 50,000 | 110,000 |

| 6 | 160,000 | 50,000 | 110,000 |

| 7 | 160,000 | 50,000 | 110,000 |

| 8 | 160,000 | 50,000 | 110,000 |

| 9 | 160,000 | 50,000 | 110,000 |

| 10 | 160,000 | 50,000 | 110,000 |

| 11 | 160,000 | 50,000 | 110,000 |

| 12 | 160,000 | 50,000 | 110,000 |

| 13 | 120,000 | 50,000 | 70,000 |

| 14 | 120,000 | 50,000 | 70,000 |

| 15 | 120,000 | 50,000 | 70,000 |

Over a 15-year period, mulberry farming on one acre generates a total income of NRs. 2,090,000 against total costs of NRs. 839,000, resulting in a net profit of NRs. 1,251,000 and an impressive return on investment (ROI) of about 149%.

The first year records a loss of NRs. 109,000 due to high establishment costs, but profitability begins from Year 2, with net earnings of NRs. 50,000. Peak production in Years 3–12 yields NRs. 110,000 annually, contributing NRs. 1,100,000 to total profit, while the declining yield phase in Years 13–15 still provides NRs. 70,000 per year. On average, mulberry farming delivers an annual net profit of around NRs. 89,357 from Year 2 onward, making it a sustainable and moderately high-return agricultural investment.

Sources

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

University of California Agriculture & Natural Resources (UC ANR)

European Plant Protection Organization (EPPO)

Punjab Agricultural University (PAU)

Tamil Nadu Agriculture University (TNAU) – Agritech portal

Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR)

Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC)

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Disclaimer: This crop farming profits assume optimal conditions. Actual results may vary with climate, market prices, and farm management.