Honeybee Farming

Honeybee farming, or apiculture, refers to the organized management of bee colonies with the aim of producing marketable products and providing agricultural services. This activity can be successfully undertaken on relatively small areas of land, making it suitable for both smallholders and commercial entrepreneurs. Income from beekeeping is not limited to honey alone; beekeepers also benefit from the sale of beeswax and propolis, the provision of pollination services to farmers, and the marketing of nuclei or complete colonies.

Honeybee farming profit can be highly rewarding with proper planning and management. Setting up a 20-colony apiary requires an initial investment of NRs. 2,25,000, with annual maintenance costs of NRs. 1,05,000. The operation generates an annual gross income of NRs. 4,40,000 from honey, beeswax, pollination services, and sale of nuclei or colonies, yielding a net profit of NRs. 1,10,000 in the first year and NRs. 3,35,000 from the second year onward.

The break-even point is achieved in approximately 1 year and 4 months, with a profit margin of around 76% from year two onward and a return on investment of about 149% after the first year, highlighting the lucrative potential of bee farming profit.

Honeybee

Honeybees are of great agricultural importance, not only because they produce valuable hive products but also due to their vital role in pollinating a wide range of crops. Effective pollination by honeybees contributes significantly to improved crop yields, better fruit quality, and enhanced agricultural sustainability. Among the different honeybee species found across the world, Apis mellifera, commonly known as the European honeybee, is the most widely used species in commercial beekeeping operations.

The popularity of Apis mellifera among beekeepers is largely attributed to its high honey-producing ability, strong and efficient foraging behavior, gentle nature, and adaptability to migratory beekeeping systems.

In migratory beekeeping, colonies are periodically relocated to areas with abundant flowering crops, allowing bees to exploit a wide variety of nectar and pollen sources throughout the year. This species is capable of forming large, robust colonies and performs well under intensive management conditions, making it especially suitable for large-scale and profit-oriented honey production.

In South Asia, other honeybee species are also commonly encountered, including Apis cerana indica (Indian honeybee), Apis dorsata (rock bee), and Apis florea (little bee). The Indian honeybee, Apis cerana indica, is often maintained in traditional or small-scale beekeeping systems; however, its honey yield per colony is considerably lower than that of Apis mellifera.

The rock bee (Apis dorsata) and the little bee (Apis florea) are wild species that build exposed nests and exhibit aggressive or migratory behavior. Due to these characteristics, they cannot be easily domesticated and are therefore unsuitable for commercial hive-based beekeeping.

Structure of a Honeybee Colony

A honeybee colony functions as a highly organized social system composed of three distinct types of individuals, each with specific responsibilities that contribute to the survival and productivity of the colony.

Queen Bee

The queen bee is the sole reproductive female in the colony. Her primary role is to lay eggs, with egg production reaching as many as 1,500 to 2,000 eggs per day during favorable seasons. In addition to reproduction, the queen releases chemical signals that regulate the behavior and cohesion of the colony, ensuring orderly functioning and continuous population growth.

Worker Bees

Worker bees constitute the majority of the colony population and are sterile females. They perform nearly all of the tasks required for colony maintenance, including collecting nectar and pollen, feeding and caring for the brood, constructing wax combs, cleaning the hive, regulating internal temperature, and defending the colony against intruders. Their collective effort supports both colony survival and honey production.

Drone Bees

Drone bees are the male members of the colony. Their sole biological function is to mate with a virgin queen during mating flights. Drones do not take part in foraging or hive maintenance activities. During periods when food resources are limited, they are often driven out of the colony by worker bees to conserve resources.

Bee Hives and Tools / Equipment Used in Beekeeping

Successful honeybee farming relies greatly on the use of standardized hive systems and suitable beekeeping tools. Proper equipment enables efficient colony management, facilitates regular inspection, supports disease prevention, and improves the efficiency of honey production. In modern commercial beekeeping, the Langstroth hive is the most commonly adopted hive system because of its movable-frame design, ease of handling, and high honey yield potential.

Langstroth Beehive

The Langstroth hive is constructed on the principle of bee space, a precise gap that allows bees to move freely while preventing them from sealing hive components with excess wax or propolis. This design ensures that hive parts remain movable and easy to manage. A typical Langstroth hive is made up of several key components:

Brood Box

The brood box is positioned at the base of the hive and functions as the primary nesting area of the colony. It is within this chamber that the queen lays eggs and the immature stages of bees develop. The box contains frames fitted with wax foundation sheets, which provide a guided structure for comb building. These combs are used for rearing brood as well as storing pollen and honey required for colony sustenance. Effective management of the brood box is essential for maintaining colony health and productivity.

Super Chamber (Honey Super)

The super chamber is placed above the brood box and is intended mainly for the storage of surplus honey. Since brood rearing is restricted to the lower chamber, honey supers can be removed and harvested with minimal disturbance to the colony.

Frames

Frames are removable wooden or plastic structures designed to hold wax foundation sheets. They guide bees in constructing straight and uniform combs, making hive inspection and honey extraction more efficient.

One of the main advantages of the Langstroth hive is its modular design, which allows beekeepers to add or remove boxes depending on seasonal changes in colony population and nectar availability.

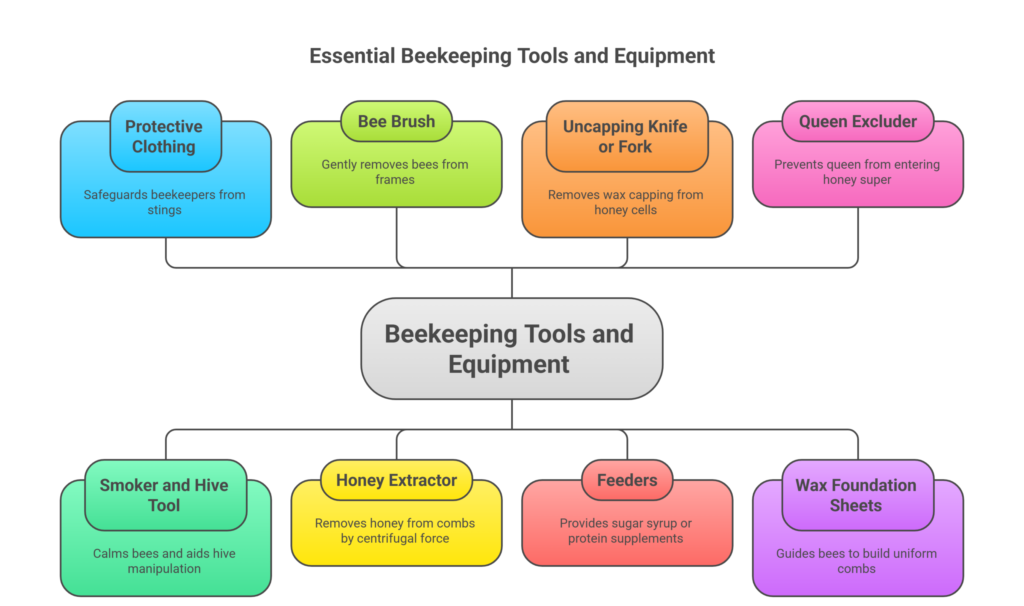

Essential Beekeeping Tools and Equipment

Protective Clothing

Beekeepers use protective clothing such as bee suits, gloves, and veils to reduce the risk of stings. This equipment enables safe handling of bees during hive inspections, colony management, and honey harvesting.

Smoker and Hive Tool

The smoker and hive tool are among the most important tools in beekeeping. The smoker produces cool smoke that masks alarm pheromones, helping to calm bees and reduce defensive behavior during inspections. The hive tool is a multipurpose instrument used to open hive boxes, loosen frames, remove propolis, and clean hive components.

Bee Brush

A bee brush with soft bristles is used to gently sweep bees off frames, particularly during honey collection, without causing harm to the insects.

Honey Extractor

Honey extractors, which may be hand-operated or powered by electricity, remove honey from combs through centrifugal force. This method allows honey to be harvested without damaging the comb, enabling bees to reuse it and thereby improving production efficiency.

Uncapping Knife or Fork

Before honey extraction, the thin wax layer sealing mature honey cells must be removed. Uncapping knives or forks are used for this purpose and may be heated or unheated depending on the size and scale of the beekeeping operation.

Feeders

Feeders are used to supply sugar syrup or protein supplements during periods when natural nectar and pollen sources are insufficient. Commonly used feeders include entrance feeders, frame feeders, and top feeders.

Queen Excluder

A queen excluder is a grid made of metal or plastic that is placed between the brood chamber and the honey super. It allows worker bees to pass through while preventing the queen from entering the honey super, ensuring that honey frames remain free of brood.

Wax Foundation Sheets

Wax foundation sheets are thin layers of beeswax embossed with a hexagonal cell pattern. These sheets guide bees in building regular and well-structured combs, helping them save energy and make efficient use of space for honey storage.

Preparation of Artificial Feeds for Different Seasons

Providing supplementary feed is an important colony management practice in beekeeping, especially during periods when flowering plants are scarce and natural sources of nectar and pollen are limited or absent. Seasonal gaps in forage availability can lead to reduced brood production, weakened colonies, and lower overall productivity. Properly planned artificial feeding supports colony growth, sustains brood rearing, and helps prepare bee colonies for forthcoming honey flow periods.

Sugar Syrup Feeding

Sugar syrup is widely used as a substitute for natural nectar and supplies the carbohydrates needed by honeybees for energy, wax secretion, and brood care. The strength of the syrup is adjusted according to seasonal conditions and the specific needs of the colony.

1:1 Sugar Syrup (Stimulative Feeding)

A sugar-to-water ratio of 1:1 is typically provided during early spring or just before major flowering seasons. This lighter syrup encourages increased egg laying by the queen and promotes active brood rearing. By stimulating colony expansion, it helps build a strong workforce in anticipation of abundant nectar availability.

2:1 Sugar Syrup (Maintenance Feeding)

A more concentrated syrup, prepared using a 2:1 sugar-to-water ratio, is generally fed during winter months, extended dry periods, or times of prolonged nectar shortage. This thicker solution closely resembles stored honey, making it easier for bees to process and store. It supports colony survival, minimizes stress, and helps prevent starvation during unfavorable environmental conditions.

Preparation Method

Sugar syrup should be prepared using clean drinking water. The water should be gently warmed to help dissolve the sugar thoroughly, but it should not be boiled, as excessive heating can cause caramelization that may be harmful to bees. Once the sugar has fully dissolved, the syrup should be allowed to cool to room temperature before being offered to the colonies.

Season-Wise Feeding Schedule

Season | Floral Availability | Feed Type | Sugar Syrup Ratio | Quantity per Colony | Feeding Frequency | Purpose |

Spring (Pre-Honey Flow) | Moderate | Sugar syrup | 1:1 | 500–750 ml | 2–3 times/week | Stimulate brood rearing & colony buildup |

Summer (Peak Nectar Flow) | Abundant | Not required | – | – | – | Natural honey production |

Monsoon / Rainy Season | Low | Sugar syrup + protein | 1:1 | 500 ml syrup + 100 g protein patty | 2 times/week | Maintain colony strength |

Autumn (post-harvest) | Declining | Sugar syrup | 2:1 | 750 ml–1 L | Once/week | Rebuild food reserves |

Winter / Dearth Period | Very low | Sugar syrup + protein | 2:1 | 1–1.5 L syrup + 150 g protein patty | Once every 7–10 days | Prevent starvation & brood loss |

Protein Supplement (Pollen Substitute)

Pollen is the primary source of protein, lipids, vitamins, and minerals for honeybees and is vital for brood rearing and larval development. During pollen-deficient periods, pollen substitutes are provided to maintain healthy brood production.

Season | Protein Patty Quantity |

Monsoon | 100 g per colony |

Winter | 150–200 g per colony |

Severe pollen scarcity | Up to 250 g (split into 2 feedings) |

Common Pollen Substitute Formula

When natural pollen sources are scarce, a protein-rich pollen substitute can be prepared to support brood rearing and colony development. Commonly used formulations include soybean flour or chickpea flour as the primary protein component, combined with powdered sugar to supply energy. A small amount of natural honey is often added to improve acceptance by the bees and to help bind the ingredients together. These components are thoroughly mixed to form a soft patty or dough, which is then placed inside the hive close to the brood nest so that nurse bees can easily consume it and feed the developing larvae.

Best Feeding Practices in Honeybee Farming

Effective feeding management is essential to ensure colony safety and product quality. Artificial feed should preferably be provided during the evening hours, as this reduces the likelihood of robbing by neighboring colonies. Enclosed feeding methods, such as frame feeders or top feeders, are recommended over open feeding to maintain hygiene and allow better control over feed intake.

Only clean water and refined white sugar should be used when preparing sugar syrup to prevent contamination and potential harm to the bees. Supplementary feeding must be avoided during periods of heavy nectar flow, as it can lead to the adulteration of harvested honey. Additionally, reducing the hive entrance while feeding helps limit excessive bee movement, lowers the risk of robbing, and minimizes disturbance within the colony.

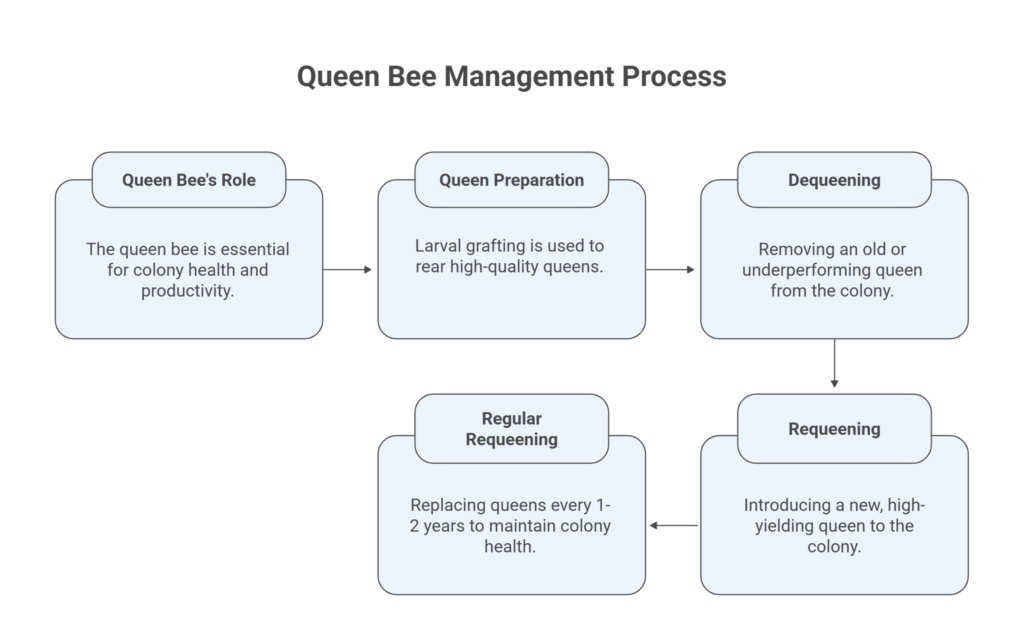

Queen Management: Preparation, Dequeening, and Requeening Practices

The success of a honeybee colony largely depends on the quality and performance of its queen. As the sole egg-layer, the queen directly influences colony population growth, workforce strength, resistance to disease, and honey production. Colonies headed by young and vigorous queens generally show strong brood patterns and high productivity, while those with aging or poorly performing queens often experience reduced efficiency and declining yields.

Queen Preparation

Queen preparation focuses on producing superior queens through controlled and planned rearing methods. One of the most reliable approaches involves raising queens from very young larvae obtained from colonies known for desirable traits such as high honey yield, good temperament, and disease tolerance.

These larvae are carefully placed into specially designed queen cells and introduced into a colony that has temporarily been made queenless. The absence of a queen stimulates worker bees to supply large quantities of royal jelly, allowing the larvae to develop into reproductive queens.

After the queen cells mature, they are transferred to mating nuclei or designated colonies where the queens emerge, mate, and are observed for performance. Successful queen rearing depends heavily on colony nutrition; therefore, this process should be conducted during periods of strong nectar availability or supported by supplemental feeding to ensure optimal queen development and longevity.

Dequeening

Dequeening involves deliberately removing an existing queen from a colony when her performance no longer meets production requirements. This step may be necessary if the queen exhibits poor egg-laying patterns, uneven brood development, excessive drone production, physical damage, or signs of illness. Removing an ineffective queen at the right time prevents further weakening of the colony and creates favorable conditions for the introduction of a more productive replacement.

Requeening

Requeening is the process of introducing a new, high-quality queen into a colony after the old queen has been removed. The new queen is commonly placed inside a protective cage that allows worker bees to gradually accept her presence. Leaving the colony without a queen for a short period, typically between 12 and 24 hours, increases the likelihood of successful acceptance.

Requeening is most effective during nectar flow seasons, when colonies are calmer and less defensive. Once accepted, the new queen usually begins laying eggs within a few days, leading to renewed colony growth and improved performance.

Importance of Regular Requeening

Replacing queens on a regular schedule, usually every one to two years, is a widely adopted management strategy in both commercial and small-scale beekeeping. Consistent requeening helps maintain strong brood production, reduces the risk of swarming, improves colony stability, and enhances overall honey yields. Effective queen management is therefore essential for sustaining healthy, productive, and economically profitable honeybee colonies.

Bee Colony Transfer and Transportation of Live Hives

Relocating honeybee colonies from one location to another, commonly known as migratory beekeeping, is an important management practice used to sustain colony activity and improve honey production throughout the year.

By moving hives to regions where flowering plants are abundant at different times, beekeepers can ensure continuous access to nectar and pollen. This practice not only supports stronger colony development and higher honey yields but also contributes significantly to agricultural pollination, benefiting crop productivity and ecosystem balance.

Best Practices for Transporting Bee Colonies Safely

The movement of live bee colonies must be carefully managed to reduce stress on the bees and prevent damage to the hive. Proper handling during transportation helps maintain colony strength and productivity. The following measures are essential for safe hive movement:

Transportation During Cooler Hours

Colonies should be moved during nighttime or early morning when temperatures are lower and bees are less active. Transporting hives during these periods minimizes bee flight, reduces agitation, and makes handling safer and more efficient.

Use of Ventilated Entrance Barriers

Hive entrances should be closed using breathable materials such as wire mesh prior to transport. This keeps bees confined within the hive while allowing sufficient airflow, preventing overheating and suffocation during transit.

Stabilization of Internal Frames

All frames inside the hive must be firmly secured to prevent movement. Unstable frames can break combs, crush brood, and spill honey, which weakens the colony and reduces honey recovery.

Ensuring Proper Air Circulation

Adequate ventilation is critical while colonies are in transit. Hives should be positioned to allow airflow and protected from excessive heat, direct sunlight, rain, and dust, all of which can increase stress and mortality.

Crops Commonly Targeted in Migratory Beekeeping

The timing of colony movement is closely aligned with the flowering cycles of nectar- and pollen-rich crops. Early-season plants such as mustard provide initial nectar flows, while crops like litchi and sunflower support mid-season foraging. Long-flowering trees such as eucalyptus offer extended nectar availability, and fruit orchards including mango, guava, and citrus supply valuable nectar and pollen during their bloom periods.

Strategically transferring colonies to these crops at peak flowering stages allows beekeepers to maximize honey harvests and maintain healthier colonies. Well-managed hive transportation can substantially increase honey output per colony, improve colony vitality through exposure to diverse floral sources, reduce pest and disease pressure associated with fixed apiaries, and create opportunities for income through commercial pollination services.

Identification of Bee Flora: Sources of Nectar, Pollen, and Propolis

The success of beekeeping operations is strongly influenced by the type, availability, and diversity of flowering plants surrounding an apiary. Honeybee colonies depend on plants for three essential resources—nectar, pollen, and propolis—each of which supports different aspects of colony growth, nutrition, and productivity.

Effective apiary planning aims to ensure a steady supply of these floral resources throughout the year, preferably within a radius of about three kilometers, which corresponds to the normal foraging distance of honeybees.

Nectar-Producing Plants

Nectar serves as the main energy source for honeybees and is converted into honey through processing and storage within the hive. The abundance and quality of nectar-producing plants in a given area have a direct impact on honey yield. Regions dominated by plants with high nectar secretion typically support stronger colonies and higher honey production. Identifying and utilizing such nectar-rich flora is therefore essential for maximizing apiary output.

Plant Name (Common & Scientific) | Key Characteristics & Benefits | Primary Season of Nectar Flow |

Mustard (Brassica spp.) | Early-season nectar flow; highly attractive to bees, stimulates colony buildup. | Early Season (e.g., Winter/Spring) |

Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) | Provides abundant nectar and pollen simultaneously; supports both honey production and brood rearing. | Mid to Late Season (Summer) |

Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) | Excellent late-season nectar source; helps colonies build food reserves. | Late Season (Autumn) |

Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus spp.) | Long flowering duration; produces high-quality honey in large volumes. | Extended/ Multiple Seasons |

Litchi (Litchi chinensis) | Mid-season nectar flow; supports strong brood development and honey storage. | Mid-Season (Spring/Summer) |

Citrus (Orange, Lemon, Grapefruit) | Provides fragrant nectar; enhances the aroma and flavor of the honey. | Early to Mid-Season (Spring) |

Pollen Sources

Pollen is the primary protein source for honeybees and is essential for brood rearing, gland development, and overall colony growth. Common pollen sources include:

Plant Name / Category | Key Characteristics & Benefits | Role in Colony Health |

Maize (Zea mays) | Widely available; provides high-protein pollen essential for larval development. | Supports brood rearing and colony growth due to high protein content. |

Sorghum (Sorghum spp.) | Supports brood rearing effectively during the mid-season; a reliable pollen source. | Maintains colony strength and continuous brood production in mid-season. |

Legumes (e.g., Clover, Chickpea, Lentils) | Rich in essential amino acids; crucial for overall colony health and immune function. | Enhances bee nutrition, resilience, and supports healthy gland development. |

Wild Weeds & Flowering Herbs | Serve as supplementary pollen sources, especially during periods of nectar/pollen dearth. | Provides vital diversity and ensures protein availability during scarce seasons, preventing colony decline. |

Propolis Sources

Propolis, also known as bee glue, is collected from tree resins and used by bees for hive maintenance, structural support, and antimicrobial defense. Major propolis sources include:

Plant/Tree Name (Common & Scientific) | Key Characteristics & Properties | Primary Contribution to the Hive |

Poplar (Populus spp.) | High resin content; produces dark, sticky propolis. | Main source for sealant and structural hive maintenance. |

Pine (Pinus spp.) | Rich in resin; contributes strong defensive properties. | Enhances hive defense against pathogens and pests. |

Neem (Azadirachta indica) | Possesses natural antimicrobial and antifungal properties. | Significantly boosts the propolis’s medicinal and protective quality. |

Sal (Shorea robusta) | Common in tropical regions; resin enhances overall propolis quality. | Improves durability and therapeutic value of the bee glue. |

Planning a Year-Round Floral Calendar

Effective apiary management requires careful selection and arrangement of flowering plants to ensure a steady supply of nectar, pollen, and propolis throughout the year. This involves assessing the surrounding landscape within approximately a three-kilometer radius and positioning colonies close to plant species that bloom in succession across different seasons.

Systematic identification and management of bee-friendly flora help maintain uninterrupted foraging opportunities, supporting consistent honey yields and continuous brood development. Such planning also reduces nutritional stress during periods of floral scarcity and contributes to stronger, healthier, and more productive colonies, making beekeeping operations both sustainable and economically viable.

Month | Major Nectar Sources | Major Pollen Sources | Major Propolis Sources | Remarks / Notes |

January | Mustard, Citrus | Maize, Legumes | Poplar, Pine | Early-season nectar; ideal for colony buildup |

February | Mustard, Sunflower | Maize, Clover | Neem, Sal | Stimulates brood rearing and honey storage |

March | Sunflower, Buckwheat | Chickpea, Wild legumes | Pine, Poplar | High honey flow; start harvesting late March |

April | Eucalyptus, Citrus | Sorghum, Clover | Neem, Sal | Mid-season honey production; monitor colony strength |

May | Eucalyptus, Litchi | Maize, Wild weeds | Poplar, Pine | Nectar flow continues; ensure feeding during dearth patches |

June | Litchi, Sunflower | Sorghum, Legumes | Neem, Sal | Peak brood rearing; supplementary feeding if needed |

July | Buckwheat, Eucalyptus | Maize, Chickpea | Poplar, Pine | Continuous honey production; prepare for monsoon |

August | Eucalyptus, Litchi | Wild legumes, Sorghum | Neem, Sal | Ensure hives are protected from heavy rains |

September | Sunflower, Mustard | Legumes, Maize | Poplar, Pine | Late-season nectar; focus on colony strengthening |

October | Mustard, Citrus | Chickpea, Clover | Neem, Sal | Post-harvest flow; start harvesting surplus honey |

November | Buckwheat, Sunflower | Maize, Legumes | Poplar, Pine | Nectar scarcity may start; provide supplemental feeding |

December | Citrus, Mustard | Wild legumes | Neem, Sal | Low natural flow; feeding essential for colony survival |

Honey Harvesting, Processing, and Storage

Harvesting

Honey collection should be carried out only after most of the comb cells have been sealed by the bees, usually when about four-fifths or more of the cells are capped. This stage indicates that the honey has matured and contains a safe level of moisture.

Collecting honey prematurely often results in thin honey that is prone to fermentation, while delaying harvest for too long may limit total yield. Frames containing brood must be left undisturbed, as their removal can weaken the colony and disrupt future honey production. Calm handling techniques, along with the controlled use of a smoker, help reduce disturbance and stress to the bees during harvesting.

Processing

After removal from the hive, honey is processed to make it clean and suitable for consumption and sale. The first step involves removing the thin wax layer that seals the comb cells, which can be done manually or with specialized equipment.

The exposed combs are then placed in an extractor, where spinning force separates the honey from the wax structure. The extracted honey is passed through fine filters to eliminate wax fragments and other impurities. It is then allowed to stand undisturbed so that trapped air bubbles and remaining particles rise to the surface, resulting in a clear and uniform product.

Storage

Maintaining appropriate storage conditions is essential for preserving honey quality over time. Honey should be kept in clean, food-safe containers that do not react to its natural components. Storage areas should be cool, dry, and protected from sunlight, as excessive heat and moisture can negatively affect texture and flavor and may promote fermentation. Ensuring that the moisture level of stored honey remains below approximately eighteen percent is especially important for preventing spoilage and extending shelf life.

Overall, careful management of harvesting, processing, and storage practices helps preserve honey’s natural taste, nutritional properties, and commercial value, while supporting sustainable beekeeping and long-term colony health.

Cost of Investment for 20 bee Colonies

S.N. | Item Description | Quantity Required (For 20 Colonies) | Estimated Unit Price (NRs.) | Total Cost (NRs.) | Remarks |

1. | Bee Colonies with Hives | 140,000 | Largest single cost component. | ||

a. Langstroth Hive (Complete set: Brood box, super, frames, lid, bottom board) | 20 sets | 5,000 | 100,000 | Standard hive for Apis mellifera. | |

b. Live Bee Colony (Package or established colony) | 20 colonies | 2,000 | 40,000 | Cost for the bees themselves. | |

2. | Essential Beekeeping Tools & Equipment | 50,000 | One-time purchase for the apiary. | ||

a. Bee Suit with Veil & Gloves | 2 sets | 8,000 | 16,000 | Protective gear. | |

b. Smoker | 2 pieces | 1,500 | 3,000 | ||

c. Hive Tool | 4 pieces | 500 | 2,000 | ||

d. Honey Extractor (Manual, 4-frame capacity) | 1 unit | 25,000 | 25,000 | Can be shared among colonies. | |

e. Uncapping Knife & Fork set | 1 set | 2,000 | 2,000 | ||

f. Bee Brush | 2 pieces | 500 | 1,000 | ||

g. Feeders (Frame/Entrance type) | 20 pieces | 300 | 6,000 | ||

h. Queen Excluders | 20 pieces | 250 | 5,000 | ||

3. | Miscellaneous & Setup Costs | 35,000 | Infrastructure and consumables. | ||

a. Wax Foundation Sheets | 200 sheets | 80 | 16,000 | For frames in brood and super boxes. | |

b. Stand/Bench for Hives | 20 stands | 500 | 10,000 | To protect hives from ground moisture/pests. | |

c. Initial Feed (Sugar, Supplements) | – | – | 5,000 | For colony establishment. | |

d. Transportation, Labor, Contingency | – | – | 4,000 | Initial setup and installation. | |

Total Estimated Initial Investment | NRs. 2,25,000 |

Maintenance Cost for 20 bee Colonies per year

S.N. | Cost Category | Estimated Annual Cost (NRs.) | Remarks |

1. | Artificial Feeding (Sugar, Protein patty ingredients) | 40,000 | Major recurring cost during dearth seasons (Monsoon, Winter). |

2. | Hive Maintenance & Replacement (New frames, foundation, repair) | 20,000 | Regular replacement of old combs, repair of hive parts. |

3. | Queen Rearing/Replacement (New queens for requeening) | 15,000 | Requeening 30-50% of colonies annually for productivity. |

4. | Medicine & Pest Control (For Varroa, wax moth, etc.) | 10,000 | Preventive and therapeutic treatments. |

5. | Labour & Transportation (For hive inspection, migration) | 15,000 | Cost for partial hired labor or own labor estimation. |

6. | Miscellaneous & Contingency | 5,000 | Cleaning materials, fuel, etc. |

Total Estimated Annual Maintenance Cost | NRs. 1,05,000 |

Income from 20 bee Colonies per year

Income Source | Quantity (Kg) / Colony | No. of Colony | Total Yield (Kg) | Rate (NRs.) / Kg | Total Income (NRs.) |

Honey | 25 | 20 | 500 Kg | 700 | 350,000 |

Beeswax | 1 | 20 | 20 kg | 1000 | 20,000 |

Pollination services | – | – | 30,000 | ||

Sale of nuclei / colonies | – | – | 40,000 | ||

Total Gross Income | 440,000 |

Analysis of Honeybee Farming Profit for 20 Colonies

Description | Amount (NRs) |

Initial investment | 2,25,000 |

Annual maintenance cost | 1,05,000 |

Annual gross income | 4,40,000 |

Annual net profit (Year 2 onward) | 3,35,000 |

Year 1 net profit | 1,10,000 |

Break-even point | 1 year 4 months |

Profit margin (Year 2 onward) | ≈76% |

ROI after Year 1 | ≈149% |

The total initial investment for setting up a 20-colony apiary is NRs. 2,25,000, with an annual maintenance cost of NRs. 1,05,000. The annual gross income from honey, beeswax, pollination services, and sale of nuclei/colonies amounts to NRs. 4,40,000, resulting in a net profit of NRs. 1,10,000 in the first year and NRs. 3,35,000 from the second year onward. The break-even point is reached in approximately 1 year and 4 months, with a profit margin of around 76% from the second year onward and a return on investment of approximately 149% after the first year.

Sources

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

University of California Agriculture & Natural Resources (UC ANR)

Tamil Nadu Agriculture University (TNAU) – Agritech portal

Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR)

Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC)

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development (Nepal)

Dhaliwal, GS and Singh B. 2000. Pesticides and environment. Commonwealth Publishers, New Delhi, India

Gautam R. D. 2008. Biological Pest Suppression. Westville Publishing House, New Delhi, India

Naim, M. 1993. Beekeeping: pleasure and profit. Kalyani Publisher, New Delhi, India

Pratap, U. 1997. 1997. Bee flora of Hindu Kush Himalayas: Inventory and management. ICIMOD, Kathmandu, Nepal

Shukla, A. N. 2000. Beekeeping Trainers Resource Book (in Nepali), ICIMOD, Kathmandu, Nepal.