Cherry Cultivation

Cherry cultivation presents a highly profitable agricultural opportunity when implemented with proper techniques and management strategies. Successful cherry production requires careful attention to specific climatic conditions, appropriate soil types, and meticulous cultivation practices. The fruiting timeline varies by cultivar, with grafted trees typically beginning production between their 3rd to 5th year after planting. As quintessential summer fruits, cherries reach peak maturity during the warmer months, with harvest methods varying significantly based on multiple factors.

These include the tree’s architectural training system, whether the variety is sweet (Prunus avium) or sour (Prunus cerasus), the intended market use (fresh market versus processing), and available harvesting resources (manual labor versus mechanical harvesters). It’s important to note that while most cherry trees don’t bear commercially viable yields until their fourth year, mature specimens can produce substantial harvests of 30-50 pints annually.

The vibrant red and purple hues characteristic of cherries come from anthocyanins – a class of flavonoid compounds within the phenolic family that not only provide pigmentation but also offer significant antioxidant benefits, contributing to cherries’ nutritional value and health-promoting properties. Below is a comprehensive guide to cherry farming, organized into specific sections covering all critical aspects of cultivation.

Land Preparation

Land preparation for cherry farming involves clearing the land of weeds, rocks, and debris, followed by plowing and harrowing the soil to achieve a fine tilth for better root penetration. Proper drainage must be ensured to prevent waterlogging, and soil tests should be conducted to determine nutrient deficiencies and pH levels for optimal growth conditions.

Soil Type

Well-drained, fertile loamy or sandy loam soils are ideal for cherries, whereas heavy clay or wet soils should be avoided since they might cause root rot. For good plant growth and maximum nutrient availability, soil pH should be between 6.0 and 7.0 for growing cherries.

Climatic Requirements

Cherries exhibit distinct climatic preferences, with sweet cherries (Prunus avium) requiring cold winters (temperatures ≤7°C to satisfy dormancy) and warm summers (20–25°C for optimal growth), while sour cherries (Prunus cerasus), being more cold-hardy, can tolerate marginally warmer conditions. Both types flourish in regions with annual rainfall of 800–1,200 mm (supplemental irrigation may be needed in drier climates) and at elevations of 1,500–2,500 meters, which provide adequate chilling hours (most varieties need ~1,000 hours between 1.7°C and 12.8°C in winter to break dormancy).

However, cherry blossoms are highly vulnerable to late frosts, which can devastate flowers and drastically reduce fruit yield. Additionally, cherry trees struggle in areas with prolonged hot summers or brief high winter temperatures, as these conditions disrupt their growth cycle and chilling requirements.

Major Cultivars

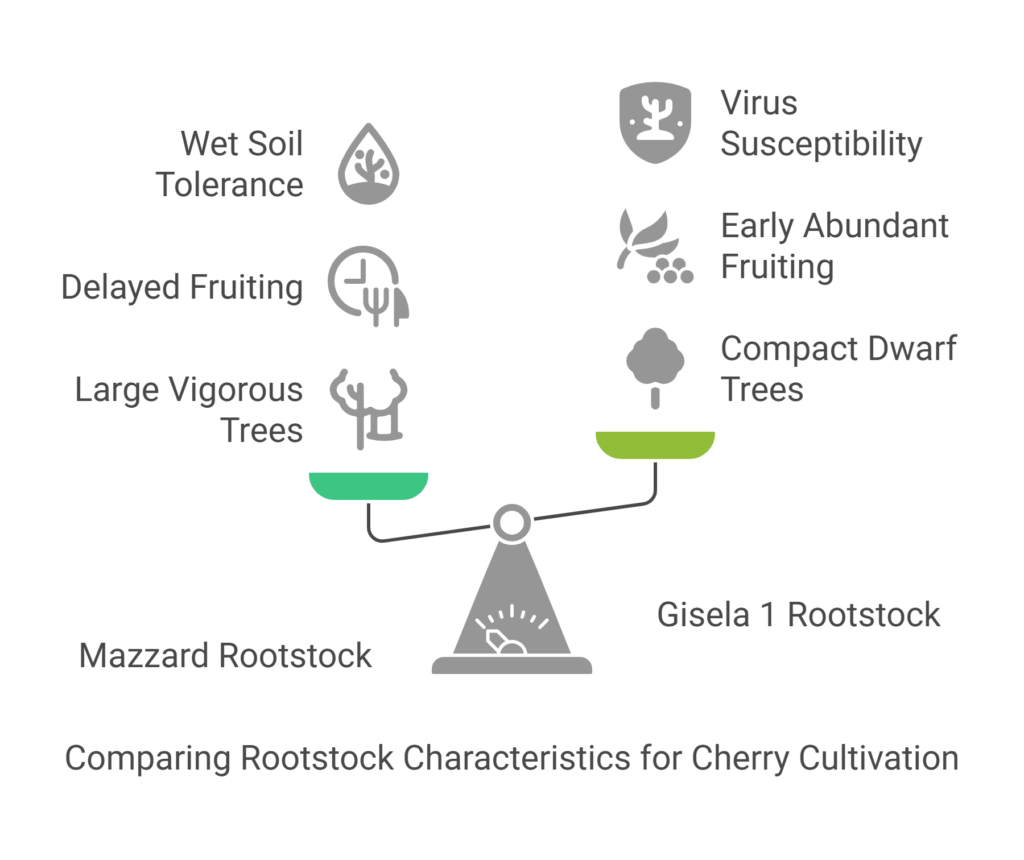

a). Rootstock Characteristics and Sweet Cherry Varieties

Mazzard rootstock, originating from wild Prunus avium (sweet cherry) seedlings, produces vigorous, large trees compatible with most cherry varieties, though it delays fruiting and offers better tolerance to wet soil conditions. In contrast, Gisela 1—a dwarfing triploid hybrid of Prunus fructicosa ‘Klon 64’ and Prunus avium—yields compact trees roughly 25% the size of Mazzard, promoting early and abundant fruiting in both sweet and tart cherries.

However, Gisela 1’s susceptibility to pollen-borne viruses like Prunus necrotic ringspot virus (PNRSV) and prune dwarf virus (PDV) necessitates careful orchard management to safeguard tree health and productivity. Meanwhile, sweet cherries (Prunus avium), celebrated for their succulent, flavorful fruit, encompass diverse cultivars, each offering unique traits in terms of taste, texture, and adaptability to growing conditions.

b). Sweet Cherry Cultivars

i). Bing

One of the most widely recognized sweet cherry varieties, Bing cherries are large, firm, and deep red to almost black when fully ripe. They have a rich, sweet flavor and are excellent for fresh eating, though they require a pollinator tree for optimal fruit set.

ii). Rainier

Known for their striking yellow skin with a red blush, Rainier cherries are exceptionally sweet with a delicate, almost honey-like taste. They are more susceptible to bird damage due to their light color but are highly sought after for their premium flavor.

iii). Stella

A self-pollinating variety, Stella cherries eliminate the need for a separate pollinator tree, making them a great choice for smaller orchards or home gardens. The fruit is dark red, sweet, and juicy, similar to Bing but with the added benefit of self-fertility.

iv). Lapins

Another self-fertile variety, Lapins cherries are crack-resistant, making them more resilient to rain-induced splitting. They produce large, dark red fruit with a balanced sweet-tart flavor and are a reliable choice for consistent yields.

c). Sour Cherries (Prunus cerasus)

Tart cherries, or sour cherries (Prunus cerasus), are valued for their vibrant acidity and a variety of culinary applications, including pies, preserves, juices, and dry snacks. In contrast to sweet cherries, they are usually too sour to consume raw, but they take on a lovely transformation when cooked or processed. Important commercial and home-garden types consist of:

i). Montmorency

The most widely grown sour cherry, Montmorency is the classic choice for pies, jams, and commercial processing (juices, frozen, and dried products). Its vibrant red skin and yellow flesh offer a bold, tangy flavor that mellows when cooked or sweetened. This hardy, self-fertile variety thrives in cooler climates and is a staple in North American orchards.

ii). Morello

Distinguished by its deep red flesh and juice, Morello cherries are intensely tart with a complex, wine-like flavor. They hold their shape and color well when cooked, making them ideal for syrups, liqueurs (like kirsch), and gourmet preserves. European in origin, Morello types (including cultivars like ‘English Morello’) are often grown as dwarf trees, suitable for small gardens or trained against walls.

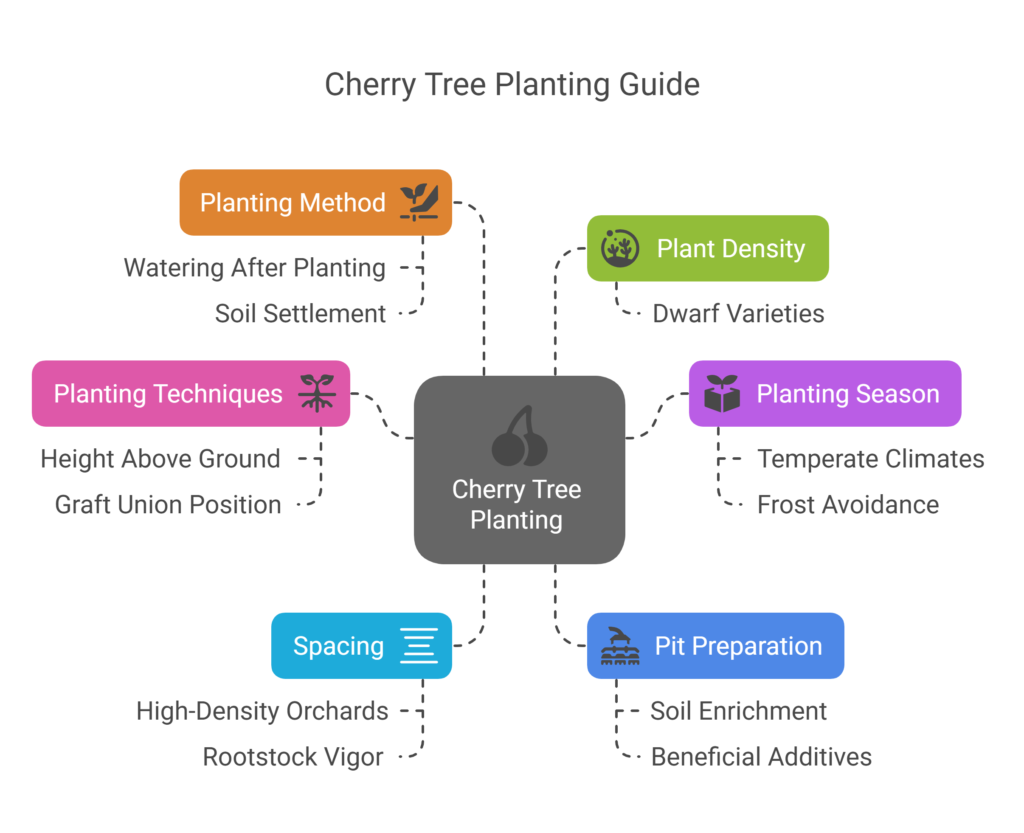

Planting

Cherry trees should be planted 30 to 40 cm above the ground to encourage primary branching. They should also be placed in a sunny, well-ventilated area that receives at least 6 hours of sunlight each day, away from buildings or taller trees that could shadow them.

When placing grafts, make sure the union is a few inches below soil level for ordinary rootstocks and slightly above for dwarf rootstocks. Fan-trained trees should be spaced 12 to 15 feet apart, and supports should be installed first. For potted trees, remove the rootball, trim any circling roots, and plant without covering the top of the rootball. For bareroot trees, spread the roots over a small soil mound and backfill gently, avoiding bending roots.

a). Planting Season

Climate determines the best time of year to plant cherry trees; in temperate climates, late winter or early spring (during dormancy) is excellent since it gives roots time to establish before spring growth. To protect young trees from harm, planting should be avoided at times when frost is likely to occur. Fall planting, if done well before freezing temperatures, may also be successful in regions with moderate winters. Better root development and tree survival are guaranteed with the right timing.

b). Spacing

For high-density cherry orchards with dwarf or semi-dwarf trees, a spacing of 5 meters between rows and 3 meters between trees within the row is recommended, allowing sufficient room for growth while maximizing land use efficiency. This configuration facilitates easier pruning, harvesting, and sunlight penetration while accommodating machinery access in commercial operations. The exact spacing may vary slightly depending on rootstock vigor and training system.

c). Pit Preparation

For proper pit preparation, dig holes measuring 60 cm × 60 cm × 60 cm, then enrich the excavated topsoil by mixing in 10 kg of well-decomposed manure along with 100g of single super phosphate, 100g of Trichoderma viride (a beneficial fungus), and 50g of biofertilizers—including nitrogen-fixing bacteria, phosphate-solubilizing bacteria (PSB), and potassium-mobilizing bacteria—to enhance soil fertility and promote healthy root development before planting.

d). Planting Method

In order to prevent the scion from roots, place the seedling in the middle of the prepared pit and fill it up with dirt, keeping the graft union 2 to 3 cm above the ground. To settle the soil and supply the necessary moisture for root formation, give the seedling plenty of water after planting. This technique guarantees healthy growth and avoids possible problems like water stress or scion roots.

e). Number of Plants per Acre

Dwarf varieties: 270 plants/acre.

Intercropping

Intercropping is suitable for young cherry orchards during the first 3–4 years, and good intercrop options include legumes (such as beans and peas), strawberries, or low-growing vegetables, as they do not compete aggressively for resources; however, tall crops should be avoided since they can compete with young cherry trees for sunlight and nutrients, potentially hindering their growth and development.

Irrigation

Cherry Tree Irrigation Guide

| Growth Stage | Water Volume per Session | Frequency | Key Notes | |

| Planting (Year 1) | 20 L Per Tree | 1st few weeks: 2–3 times / week → then 1 time / week | Keep soil moist but not soggy. Mulch to retain moisture. Avoid trunk wetting. | |

| Young Trees (Years 2–4) | 60–100 L per Tree | Every 7–10 days (2 times / week in hot/dry climates) | Deep watering encourages root growth. Adjust for soil type (sand/clay). | |

| Mature Trees (Years 5+) | 75–110 L per tree | Every 10–14 days (weekly in droughts/fruiting) | Critical periods: Flowering, Fruit Development, Post-Harvest. | |

| Dwarf/Rootstock Trees | 40–75 L per tree | More frequent (shallow roots) | Monitor soil moisture closely. | |

| Winter (Dormancy) | 20–40 L if needed | Minimal (only if frost-free & dry) | Reduce watering to prevent root rot. |

Fertilizer and Manure Management for Cherry Trees

a). Basal Application (At Planting)

For basal application at planting time, enrich each pit with 10kg of well-decomposed Farmyard Manure (FYM), 100g of Single Super Phosphate (SSP), 100g of Trichoderma (a beneficial fungus for disease prevention), and 50g of biofertilizer (containing nitrogen-fixing bacteria, Phosphate Solubilizing Bacteria/PSB, and potassium-mobilizing microbes) to ensure strong root development, improved nutrient availability, enhanced disease resistance, and vigorous early growth of the cherry sapling.

b). Annual Fertilizer Application (Per Tree)

Years 1–3 (Young Trees):

For young cherry trees (Years 1-3), apply annual fertilizer at 50-100g Nitrogen (N), 25-50g Phosphorus (P), and 50-100g Potassium (K) per tree, splitting the doses into pre-monsoon and post-fruiting applications to prevent nutrient leaching while maintaining consistent nourishment throughout the growing season.

Mature Trees (4+ Years):

For mature cherry trees (4+ years old), apply annual fertilizer at rates of 500g Nitrogen (N), 250g Phosphorus (P), and 500g Potassium (K) per tree, dividing the total amount into 2-3 split applications timed for early spring (to support new growth), fruit development stage (to enhance fruit quality), and post-harvest (to aid tree recovery and bud formation) to maximize nutrient absorption and tree productivity throughout the growing season.

Foliar Nutrition

During flowering, apply micronutrient sprays (Zinc (Zn) and Boron (B)) to improve fruit set and prevent deficiencies (e.g., poor pollination, fruit cracking).

Weed Control

Effective weed control in cherry orchards requires a multi-pronged approach: applying organic mulch (such as straw or wood chips) around the tree base effectively suppresses weed growth while retaining soil moisture; regular manual weeding near the trunk is essential to eliminate competition for nutrients and water; when chemical intervention is necessary, carefully apply pre-emergent herbicides like glyphosate, taking strict precautions to prevent direct contact with the trees to avoid damage, ensuring these are used as a last resort within an integrated weed management system.

Pest and Disease Management

Major Pests

Cherry orchards face several significant pest challenges that require targeted management strategies: The cherry fruit fly, a major threat to fruit quality, can be effectively controlled through a combination of pheromone traps for monitoring, neem oil applications as an organic deterrent, and spinosad sprays for direct treatment of infestations.

Aphid colonies, which weaken trees by sucking sap and spreading viruses, can be managed through selective insecticide sprays like imidacloprid or through biological control by introducing natural predators such as ladybugs. Bird damage, particularly during fruit ripening, necessitates protective measures including physical barriers like fine-mesh netting over trees or visual deterrents such as reflective tapes that create disorienting flashes of light to scare away avian pests.

Implementing these integrated pest management techniques helps maintain tree health while minimizing chemical inputs and preserving beneficial insect populations in the orchard ecosystem.

Major Diseases

To effectively manage common cherry tree diseases, apply copper-based fungicides to control brown rot (a fungal disease), use Mancozeb or sulfur sprays to treat cherry leaf spot infections, and for bacterial canker, promptly prune affected branches followed by application of copper-based bactericides to prevent further spread and protect tree health.

Harvesting

Cherries should only be harvested when fully ripe (dark red, black, or yellow), as their sugar content rises significantly in the final days before maturity. Be prepared to pick them within a week for immediate consumption or cooking. If freezing cherries, select firm ones and pick them with the stem to avoid damaging the fruit, while being careful not to harm the fruit spur to ensure future growth. Since hand-picking can damage shoots and increase infection risk, it’s best to use scissors to cut the stalks.

Cherry trees typically bear fruit in the 4rth year of planting. Sweet cherries should be harvested when fully colored and firm (May–July), while sour cherries are best picked when bright red and slightly soft. For longer shelf life, hand-pick cherries with stems attached. Young trees yield 5–10 kg per tree, while mature trees produce 20–50 kg, varying by cultivar. However, cherry orchards yielding more than 8 tons per acre often result in lower-quality fruit with poor taste and sugar content.

Conclusion

Successful cherry farming requires proper site selection, soil management, irrigation, pest control, and timely harvesting. Sweet cherries are more climate-sensitive, while sour cherries are hardier. With good care, cherry farming can be highly profitable.