Common Carp

The Common Carp Cyprinus carpio is a large, hardy freshwater fish native to Europe and Asia. It is one of the world’s most widely introduced and farmed fish species, valued for food, sport, and ornamentation (koi are domesticated varieties). Its morphology is a testament to its success as a bottom-feeding omnivore in still or slow-moving waters.

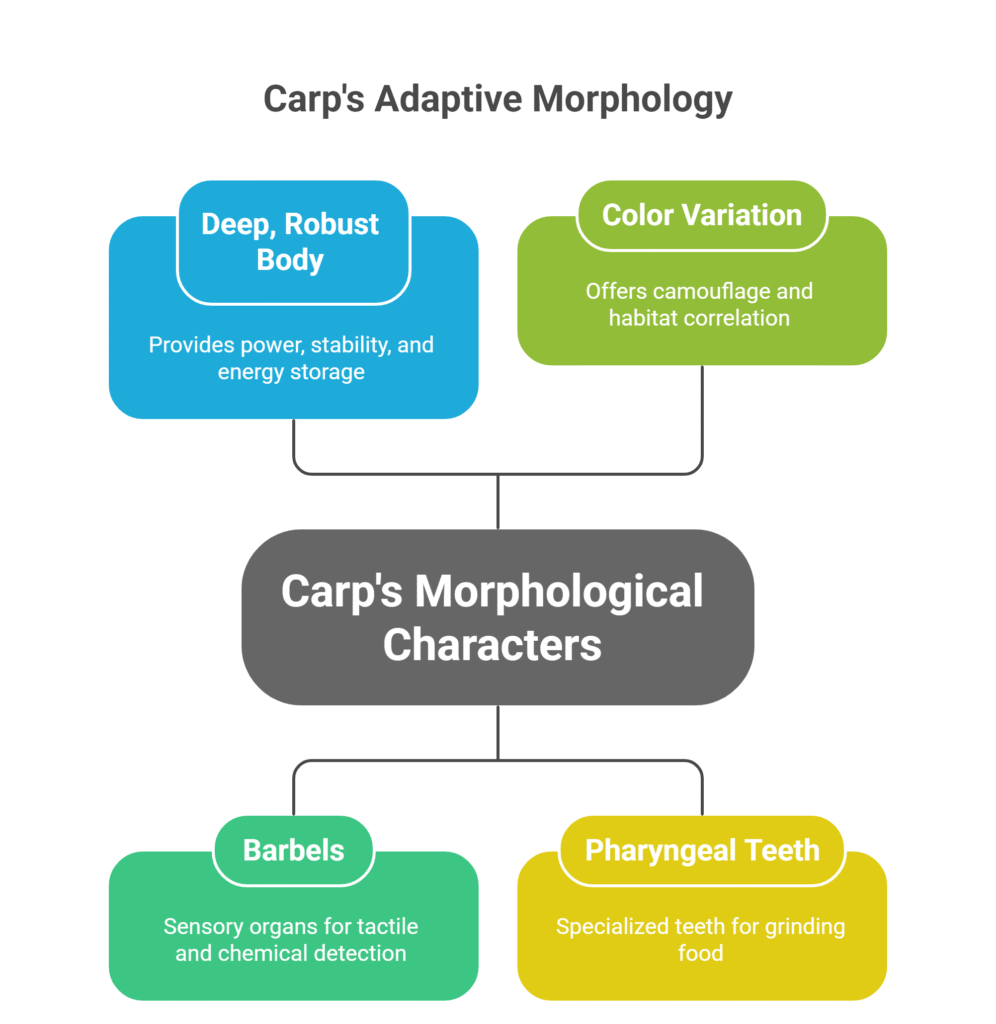

Morphological Characters

Deep, robust body with an arched back.

Common carp have a deep, robust body with a distinct arched back, a shape that plays a crucial role in their ecological adaptability. The compressed body provides a large surface area for strong muscle attachment, enabling powerful swimming bursts and giving the fish stability and resistance against currents during long migrations.

The arch, with its highest point just ahead of the dorsal fin, also creates a spacious body cavity that enhances buoyancy control and supports precise, slow-speed maneuvering in dense, vegetated habitats.

This spacious body cavity further allows carp to store significant amounts of fat, contributing to their exceptional resilience. Such energy reserves enable them to withstand periods of low food availability and survive in challenging environments, including low-oxygen waters, making them one of the hardiest freshwater fish species.

Two pairs of barbels around the mouth.

Common carp possess fleshy, whisker-like sensory organs called barbels, with one pair of longer maxillary barbels at the corners of the upper jaw and a shorter pair on the chin. These structures are characteristic of many bottom-feeding fish and serve as highly sensitive tactile and chemical sensors, containing abundant taste buds and touch receptors.

As carp forage in sediment, mud, and debris where vision is ineffective, the barbels help them “taste” and “feel” the substrate to distinguish edible materials such as insect larvae, crustaceans, and plant matter from inedible particles. Acting like underwater fingers, the barbels guide food toward the mouth and greatly enhance feeding efficiency, especially in turbid or low-visibility conditions.

Color varies from golden brown to grey.

The color of common carp varies from golden brown to grey, and this variation serves several ecological and genetic purposes. Wild carp typically display brassy olive-green to golden brown backs, yellowish sides, and lighter bellies, a countershading pattern that provides effective camouflage by hiding them from predators looking down into dark water and from prey or other fish looking up toward the bright surface.

Their coloration also shifts with habitat conditions—carp living in clear, vegetated waters tend to develop darker tones, while those in turbid or muddy environments appear more silvery or golden. Selective breeding has further diversified their appearance, especially in ornamental koi and specialized varieties like mirror and leather carp, where humans have enhanced golden hues and altered scale patterns, whereas greyish tones remain more typical in wild populations.

Pharyngeal teeth are well developed for grinding food.

Common carp lack true teeth in their jaws and instead possess specialized pharyngeal teeth located in the throat on modified gill arches known as pharyngeal arches. These molar-like teeth work against a tough keratinous chewing pad, often called the “carp stone,” forming a powerful internal grinding system essential to their feeding biology.

This mechanism allows carp to crush and process a wide range of foods, including hard-shelled mollusks, seeds, plant stems, soft insect larvae, detritus, and fibrous vegetation. Their strong pharyngeal muscles enable them to exploit food resources that many other fish cannot access, giving them remarkable dietary flexibility and contributing significantly to their ecological success as omnivorous feeders.

How These Traits Work Together

These morphological characters are not random; they form an integrated adaptive suite for a bottom-feeding generalist:

- The robust, deep bodyprovides the power and space needed for sustained foraging and survival in variable conditions.

- The barbelsact as sophisticated sensors to locate food in zero-visibility environments.

- The variable colorationallows the fish to remain inconspicuous in a range of aquatic habitats.

- The pharyngeal teethare the final, crucial processing tool, allowing it to exploit a wide range of food, especially hard-bottom-dwelling organisms.

This combination of strength, sensory sophistication, camouflage, and a highly adaptable feeding apparatus makes Cyprinus carpio an incredibly resilient and successful species, capable of thriving and dominating in diverse freshwater ecosystems worldwide.

Feeding Habits

The Common Carp’s feeding strategy is best described as an “opportunistic omnivorous bottom-feeder.” This means it eats almost anything it can find at the bottom of a water body, making it a highly successful and sometimes ecologically disruptive forager. Each component of its diet is linked to its unique morphology.

Omnivorous and Bottom-Feeder

Unlike a specialist (e.g., a piscivore that only eats fish or a herbivore that only eats plants), the carp has a broad, flexible diet. This dietary generalization is a key to its survival in new environments and its ability to thrive in conditions where food sources fluctuate.

The common carp is a specialized bottom-feeder, with a body plan fully adapted for foraging on or near the substrate. Its subterminal mouth, positioned slightly beneath the head, allows it to efficiently suck up food from the bottom, while the protractile mouth can extend like a tube to vacuum up sediments.

The sensory barbels help the carp “taste” and “feel” for edible items in the mud. Its typical feeding behavior, known as “grubbing,” involves vigorously rooting through sediment, ingesting mouthfuls of mud, sorting out food with gill rakers and the palatal organ, and expelling inedible silt and debris through the gills, a method that explains why carp are commonly found in turbid or murky waters.

Breakdown of Dietary Components

| Dietary Component | Description & Composition | Role in Diet & Nutritional Value | Carp Adaptations & Feeding Behavior |

| a) Detritus | Decomposing organic matter (dead plants, animal waste) with associated bacteria and fungi. | Abundant, constant, energy-rich source; microbes provide additional nutrition. | Ingestion while grubbing; long, coiled intestine efficiently digests complex carbohydrates to extract maximum nutrients. |

| b) Aquatic Plants | Macrophytes (e.g., pondweeds, elodea) and filamentous algae. | Provides essential carbohydrates, vitamins, and fiber; primary source in warmer months. | Pharyngeal teeth crush and grind tough stems/roots; feeding is often destructive, uprooting entire plants. |

| c) Plankton | Microscopic drifters: phytoplankton (algae) and zooplankton (e.g., Daphnia, rotifers). | Protein-rich source; critical for larval/juvenile carp; consumed by adults in open water. | Use fine gill rakers to strain plankton from inhaled water; more common behavior in younger fish. |

| d) Benthic Invertebrates | Insect larvae (midges, caddisflies), worms, snails, and clams from bottom sediments. | High-protein, high-energy core of diet; essential for growth, reproduction, and health. | Powerful pharyngeal teeth crush hard exoskeletons and shells; provides a competitive advantage. |

| e) Farm-Made Feed | Formulated pellets/extruded feeds containing proteins, carbohydrates, fats, vitamins, and minerals. | Nutritionally complete; promotes very fast growth (market size in 1–2 years vs. 4–5 in wild). | Greedily consumed at surface or while sinking; soft texture efficiently broken down by pharyngeal teeth; shows dietary flexibility. |

The Feeding Niche and Ecological Impact

The feeding habits of Common Carp establish its ecological niche as a “benthic ecosystem engineer.” In aquaculture, its ability to utilize low-quality detritus and farm waste makes it an ideal pond fish, efficiently converting waste into valuable protein.

However, in non-native ecosystems, its grubbing behavior has severe negative impacts, including resuspending sediments and increasing water turbidity, uprooting and destroying submerged vegetation, and altering food webs by consuming large amounts of invertebrates and plankton, thereby directly competing with native fish species.

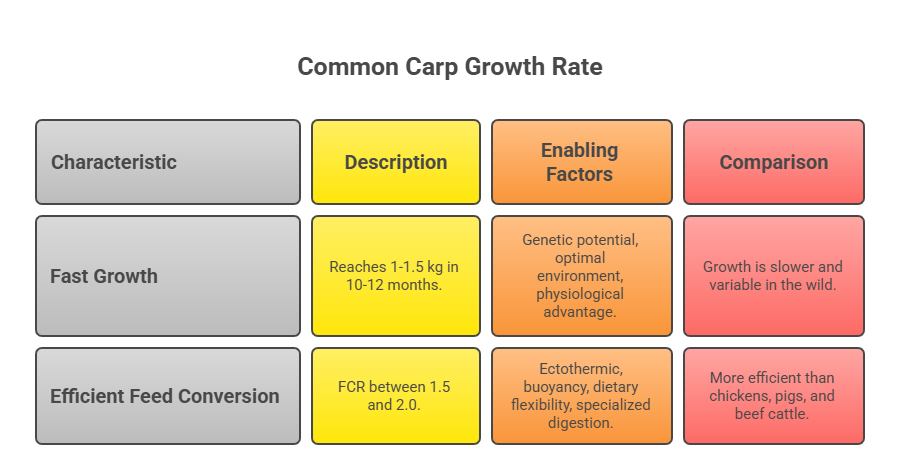

Common Carp Growth Rate

The statement highlights two interrelated and commercially critical aspects of the Common Carp’s biology: its inherent fast growth and its efficient feed conversion. These traits are the primary reasons for its global dominance in aquaculture.

Fast-Growing Species

Common Carp is a fast-growing species that can reach 1–1.5 kg within 10–12 months under pond conditions, whereas in the wild, growth is slower and variable, depending on factors such as climate, food availability, and population density.

Factors Enabling Fast Growth in Ponds

| Factor | Key Elements & Description | Impact on Growth |

| Genetic Potential | ü Centuries of domestication and selective breeding (especially in Europe and Asia). | Development of strains specifically for rapid growth, far exceeding the growth rate of wild ancestors. |

| Optimal Environment | ü Controlled stocking density ü Abundant, high-quality food (farm-made feed/fertilized ponds) ü Managed water quality (oxygen, temperature, pH) ü Predator-free setting | Reduces competition and stress; provides ideal physiological conditions; allows energy to be redirected from vigilance to growth. |

| Physiological Advantage | ü Omnivorous, generalist digestive system (long intestine, robust pharyngeal teeth) ü Natural hardiness | Enables efficient processing of diverse foods and maximum nutrient extraction. Reduces disease stress, which can stunt growth. |

Under these ideal, energy-rich conditions, carp fry (a few grams at stocking) can indeed reach a marketable size of 1-1.5 kg in less than a year. A quick “turnaround time” is crucial for achieving profitable farming.

Efficient Feed Converter

Feed conversion is one of the most important economic traits in farmed animals. The Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR) is the standard metric used to measure how much feed (by weight) is required to produce one unit of weight gain in the animal.

It is calculated using the formula: FCR = Weight of Feed Consumed ÷ Weight Gained by the Fish. A lower FCR indicates better efficiency; for example, an FCR of 1.5 means that 1.5 kg of feed produces 1 kg of fish flesh.

Common Carp are highly efficient feed converters due to several biological and ecological factors. Being ectothermic (cold-blooded), carp do not expend energy to maintain a constant body temperature, allowing a larger proportion of dietary energy to go directly into growth and metabolism. Their buoyancy in water reduces the need for heavy skeletal and muscular structures, lowering energy expenditure for movement.

Their dietary flexibility and specialized digestive anatomy further enhance feed efficiency. Carp can thrive on low-trophic-level foods and are able to digest plant-based proteins and carbohydrates efficiently using their pharyngeal teeth and long gut. In semi-intensive pond systems, carp also consume natural foods like detritus, plankton, and benthic organisms produced from pond fertilization, which supplements their diet and improves effective FCR.

In well-managed ponds, Common Carp typically achieve an FCR between 1.5 and 2.0, making them highly efficient compared to other farmed animals. For reference, chickens have an FCR of ~1.7–2.0, pigs ~2.5–4.0, and beef cattle ~6.0–10.0+, highlighting the carp’s superior feed conversion capability.

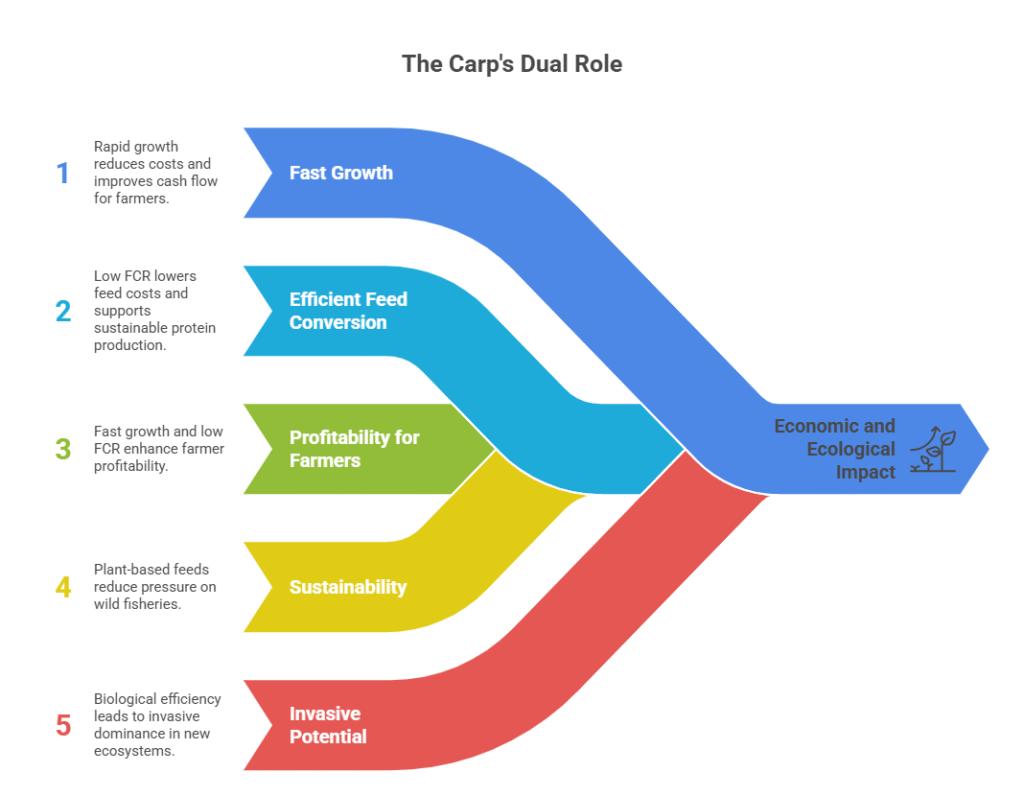

The Economic and Ecological Driver

The combination of fast growth and efficient feed conversion creates a powerful synergy:

a). Profitability for Farmers: Low FCR means lower feed costs, which typically constitute 50-60% of production expenses. Fast growth means the farmer can harvest and sell the fish quickly, reducing overhead costs (pond rental, labor, risk of disease outbreak) and improving cash flow. Reaching 1.5 kg in one year allows for one harvest per year, a predictable business model.

b). Sustainability (Relative): Because carp can grow well on feeds with lower levels of fishmeal (replaced by plant proteins), pressure on wild forage fisheries is reduced. Their efficiency at converting feed to protein makes them an important source of animal protein for a growing global population.

c). Invasive Potential (The Dark Side): This same biological efficiency is why they are devastating invaders. In a new ecosystem with no native competitors and abundant food, they grow quickly to large sizes, outcompeting native fish for resources and rapidly dominating the biomass of the water body.

The Common Carp’s growth rate is not an accident; it is the direct result of its evolutionary design as a hardy, omnivorous bottom-feeder, which has been perfectly harnessed and enhanced through aquaculture. Its efficiency at turning cheap feed into valuable flesh is the cornerstone of its status as one of the world’s most important farmed fish.

Common Carp Reproductive Behavior

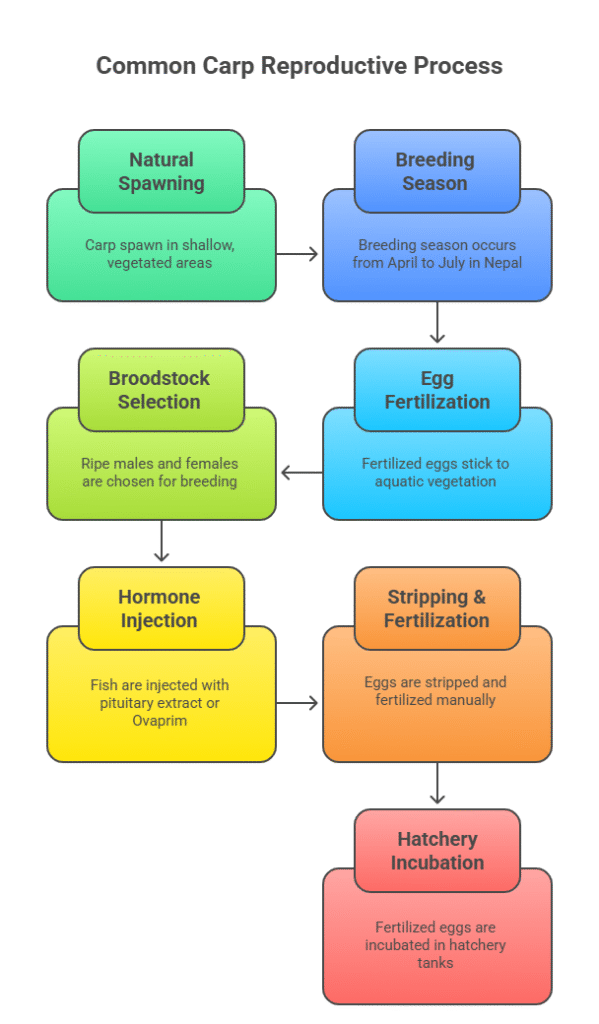

The Common Carp exhibits a reproductive strategy designed for high output in stable, productive freshwater environments. Its natural breeding behaviors are specific, but modern aquaculture often overrides these with hormonal control to maximize efficiency and production.

Spawns naturally in shallow, vegetated areas.

Common Carp naturally spawn in shallow, vegetated areas, which provide the essential environmental conditions and nursery habitat for successful reproduction.

They are photoperiodic and thermophilic spawners, requiring longer day lengths to signal the onset of the productive summer season and warm water temperatures, typically between 18–24°C (64–75°F), to trigger spawning. Shallow waters warm up fastest in the spring and summer, creating the ideal thermal environment for egg development and larval survival.

The female Common Carp does not build a nest but releases her adhesive, demersal eggs directly into the environment, making aquatic vegetation—such as submerged grasses, roots, and flooded plants—essential for successful reproduction. The sticky eggs attach to the vegetation, preventing them from sinking into oxygen-poor mud where they could suffocate or be eaten by benthic organisms.

The dense vegetation also provides physical shelter from predators for both the eggs and the newly hatched, vulnerable fry, while the biofilm and microfauna on the plants serve as the first food source for the fry upon hatching.

Breeding season: April–July in Nepal.

In Nepal, the breeding season of Common Carp occurs from April to July, reflecting the geographical and climatic application of their temperature-dependent spawning triggers.

During the pre-monsoon and monsoon seasons, rising water temperatures in April–May reach the optimal range for spawning, while the monsoon rains from June onward cause water bodies to rise, flooding shallow marginal areas and terrestrial vegetation.

This creates extensive, predator-free nursery habitats rich in attachment sites and nutrients, providing ideal conditions for carp spawning, with the slightly turbid water also offering visual cover for the adults.

Fertilized eggs stick to aquatic vegetation.

Fertilized eggs of Common Carp adhere to aquatic vegetation, detailing their deposition and early development. Spawning is communal and frenzied, with multiple males (2–4) pursuing a ripe female, nudging her flanks to encourage the release of eggs into the vegetation.

As the female releases thousands of eggs—up to 300,000+ per kg of body weight—the males simultaneously release milt to fertilize them externally. The fertilized eggs are small (1–1.5 mm), adhesive, and demersal, with a sticky outer layer that glues them to stems, leaves, and roots.

Once attached, the eggs develop in well-oxygenated water, hatching in 3–5 days depending on temperature. The newly hatched prolarvae remain attached to the vegetation by a sticky gland on their head, subsisting on their yolk sac for another 3–5 days before becoming free-swimming fry.

Induced breeding widely practiced using pituitary extract/ovaprim.

Induced breeding using pituitary extract or Ovaprim is widely practiced in modern carp aquaculture, serving as the cornerstone for overcoming the limitations and unpredictability of natural spawning.

Reasons for Induced Breeding

- Control & Predictability: Farmers can schedule spawning to align with hatchery and pond readiness, independent of erratic weather conditions.

- Synchronization: Ensures that all broodfish, both males and females, are ready to spawn simultaneously, maximizing fertilization rates.

- Higher Yield: Enables the stripping of all eggs from a female, producing a much larger harvest of fry compared to natural pond spawning.

- Genetic Management: Allows selective pairing of specific males and females to enhance desirable traits such as growth rate or disease resistance.

Methodology

Broodstock selection involves choosing ripe male and female carp that have soft, swollen abdomens, indicating they are ready for breeding.

A.Hormone Injection

- Pituitary Extract (PG): A crude extract from the pituitary glands of donor fish, containing Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) and other hormones that stimulate final egg maturation and ovulation/spermiation.

- Ovaprim/Synthetic Hormones: A refined commercial product containing a synthetic GnRH analogue combined with a dopamine antagonist, which blocks brain chemicals inhibiting ovulation, allowing effective hormone action at lower doses.

- Induced Spawning Process

- Priming Dose: A small initial dose of hormone is sometimes administered.

- Resolving Dose: A larger dose is given 6–12 hours later to trigger final maturation.

- Latency Period: Fish are held for 8–12 hours after the final injection, during which the hormones induce egg and sperm release.

- Stripping & Fertilization: The female is anesthetized and gently dried, and her eggs are manually stripped into a dry bowl. Milt from 2–3 males is then added to fertilize the eggs.

- Wetting & Stirring: Water is added to activate the sperm, initiating fertilization. The sticky fertilized eggs are then poured onto a prepared substrate, often “kakabans” made of coconut fiber or nylon, in a hatchery tank.

From Natural Strategy to Controlled Production

In nature, the carp’s reproductive strategy is a high-output, low-survival strategy. It relies on overwhelming numbers—releasing hundreds of thousands of eggs into seasonally perfect, vegetated nurseries—to ensure that enough offspring survive predation and environmental variation to sustain the population.

In aquaculture, this natural, environmentally dependent process is transformed into a high-efficiency, controlled, and predictable hatchery operation. Induced breeding ensures a reliable, dense supply of uniform fry, which are then reared under optimal pond conditions (as described in the growth section) to achieve the fast, efficient growth that makes carp farming profitable. This control over reproduction is the first critical step in the industrial production cycle of this globally important fish.

Pingback: Tilapia Farming: A Comprehensive Guide to Success