Sericulture Farming

Sericulture refers to the practice of raising silkworms for the purpose of producing silk. Unlike most other agricultural activities, it blends crop cultivation with insect rearing, making it both an agricultural and animal-based enterprise. Because of this dual nature, it has become a valuable source of income for rural households in many parts of the world.

A fundamental requirement in sericulture is the cultivation of mulberry plants, a practice known as moraculture. Mulberry leaves are the only food consumed by the domesticated silkworm species Bombyx mori. For this reason, the productivity of silk farming depends heavily on maintaining healthy mulberry plantations.

The next stage is the rearing of silkworms, which begins from the hatching of eggs and continues until the worms spin their protective cocoons. Successful rearing requires careful regulation of temperature and humidity, along with timely feeding, so that the larvae develop properly and yield strong cocoons.

Once the cocoons are collected, they undergo silk reeling, a process where the fine filaments are unwound and twisted together to form raw silk threads. These raw threads are later processed into fabrics that are valued in fashion and textile industries across the globe.

Although sericulture requires significant effort and attention to detail, it can be highly profitable. The high market value of silk ensures good returns for farmers, especially when the activity is well-managed. Beyond financial benefits, sericulture also contributes to rural development by creating jobs and sustaining the livelihoods of thousands of families.

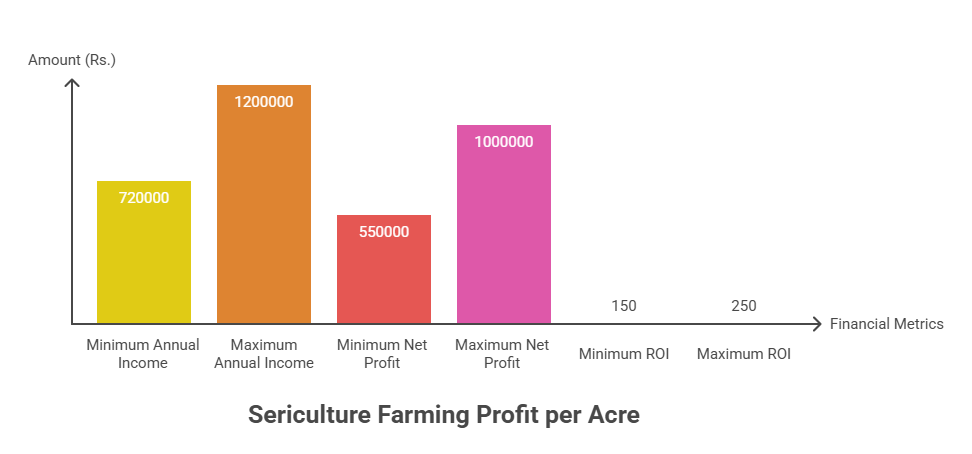

The annual income from sericulture farming per acre comes primarily from the sale of cocoons, with yields typically ranging between 800 and 1,200 kilograms per year, and at an average market price of Rs. 900 to Rs. 1,000 per kilogram, farmers can generate around Rs. 720,000 to Rs. 1,200,000 annually from a well-managed mulberry plantation and silkworm rearing system.

A detailed profit analysis of sericulture farming profit per acre reveals that after deducting annual maintenance and operational expenses, farmers can secure a net profit of approximately Rs. 550,000 to Rs. 1,000,000 each year, making it one of the most rewarding agricultural ventures. Moreover, the initial investment is typically recovered within 1 to 2 years, offering a high return on investment (ROI) of about 150% to 250%, depending on yield performance and prevailing market conditions, which highlights the lucrative potential of sericulture farming profit per acre.

Type of Silk Produced in Sericulture

While many insects are capable of spinning silk, commercial sericulture focuses mainly on a handful of species that produce fibers of economic importance. The most significant among them is mulberry silk, though several varieties of wild or “vanya” silks also play an important role in the industry.

Mulberry Silk

Mulberry Silk dominates global production, contributing over ninety percent of the world’s silk output. It is obtained from the domesticated silkworm Bombyx mori, which relies entirely on mulberry leaves as food. This silk is valued for its uniform texture, durability, natural shine, and smoothness, making it the most preferred material for high-quality garments and textiles.

Beyond mulberry, non-mulberry silks bring additional diversity to sericulture. These wild silks, each with their own distinctive appearance and cultural relevance, are often used in traditional weaving and regional crafts.

Tussar Silk

Tussar Silk comes from several wild moth species and is recognized for its rich, coarse texture and its natural golden-brown shade. It is commonly chosen for ethnic and ceremonial attire.

Eri Silk

Eri Silk sometimes referred to as “peace silk,” is unique because the moth is not harmed during collection. The resulting fiber is warm, soft, and wool-like, making it suitable for shawls, wraps, and winter clothing.

Muga Silk

Muga Silk is an exclusive variety native to Assam, India. Its golden-yellow hue and glossy finish set it apart. Remarkably strong, Muga silk is known to grow shinier with age and repeated washing, making it a symbol of prestige.

Together, these varieties demonstrate the richness and versatility of silk. From the fine smoothness of mulberry to the distinctive textures of wild silks, each type contributes to silk’s reputation as one of the most luxurious and enduring natural fibers.

Setting Up a Sericulture Farm

a). Land Selection

Establishing a productive sericulture farm begins with the careful selection of land. Since the entire process depends on a steady supply of mulberry leaves, the chosen site must provide the right conditions for vigorous mulberry cultivation.

Climate requirements are one of the first considerations. Mulberry grows best in warm, humid environments, where temperatures usually remain between 20°C and 30°C. Consistent rainfall throughout the year encourages dense leaf growth, which in turn supports the healthy development of silkworms and leads to higher cocoon yields.

Soil quality is another deciding factor. Fertile loamy or red soils that are well-drained and enriched with organic matter provide the best foundation for mulberry plantations. Ideally, the soil should maintain a pH range of 6.5 to 7.0 to ensure efficient root growth and nutrient uptake. Waterlogged or saline soils, on the other hand, can severely restrict plant performance and should be avoided.

Water availability is equally crucial. Because mulberry requires frequent irrigation, especially in dry seasons, the land should be located near a dependable water source such as a well, borehole, or canal. Reliable irrigation makes it possible to sustain multiple silkworm rearing cycles within a year.

Lastly, accessibility enhances the overall efficiency of the farm. A location with good road connections allows easy transport of mulberry leaves, cocoon collection, and movement of labor. Being closer to markets or silk-processing centers can also help minimize costs and improve profitability.

b). Mulberry Cultivation

Mulberry farming is the backbone of sericulture since its leaves serve as the exclusive diet of silkworms. Farmers typically select improved, high-yielding varieties such as V1, S36, or S54. These strains are chosen based on their adaptability to local soil and climate, ensuring a dependable supply of nutritious leaves throughout the year.

Propagation of mulberry can be done using stem cuttings or nursery-raised saplings. Once the field is prepared, the plants are usually arranged in rows with recommended spacing, such as 2 feet by 2 feet. This systematic planting provides enough room for the bushes to grow well and makes management tasks like weeding and harvesting easier.

Sustaining healthy mulberry plantations requires regular care. A balanced combination of organic manures and chemical fertilizers is applied to maintain soil fertility and enhance leaf quality. Timely irrigation, especially in dry spells, and routine weeding to minimize competition are also necessary for vigorous growth.

Among the management practices, pruning is especially important. Cutting back branches stimulates the emergence of fresh, tender leaves that silkworms feed on most efficiently. By carrying out pruning at the right intervals, farmers not only improve leaf yield but also preserve the long-term health and productivity of the plants.

Also Read: Mulberry Farming Profit Per Acre

c). Silk Rearing House (SRH)

In sericulture, the Silk Rearing House (SRH) is an essential facility that provides silkworms with a safe and well-regulated environment. Its main purpose is to shield the worms from harsh weather conditions—such as heavy rain, strong winds, or extreme heat—and from predators that could threaten their survival. By offering controlled conditions, the SRH supports healthier growth and better cocoon yields.

An effective rearing house is designed with good ventilation in mind. Windows covered with mesh allow fresh air to circulate while preventing the entry of insects and pests. The building should also be easy to sanitize, since cleanliness is vital for preventing diseases in silkworms. For this reason, smooth and non-porous flooring is often used, making it simple to wash and disinfect after each cycle of rearing.

Efficient use of space is another key feature. Different growth stages of silkworms require separate care, so farmers often set aside distinct rooms or sections for early-age rearing (chawki worms) and later stages of development. This separation helps reduce the risk of infections spreading and ensures that the worms at each stage receive the right conditions for optimal growth.

Life Cycle of the Silkworm (Complete Metamorphosis)

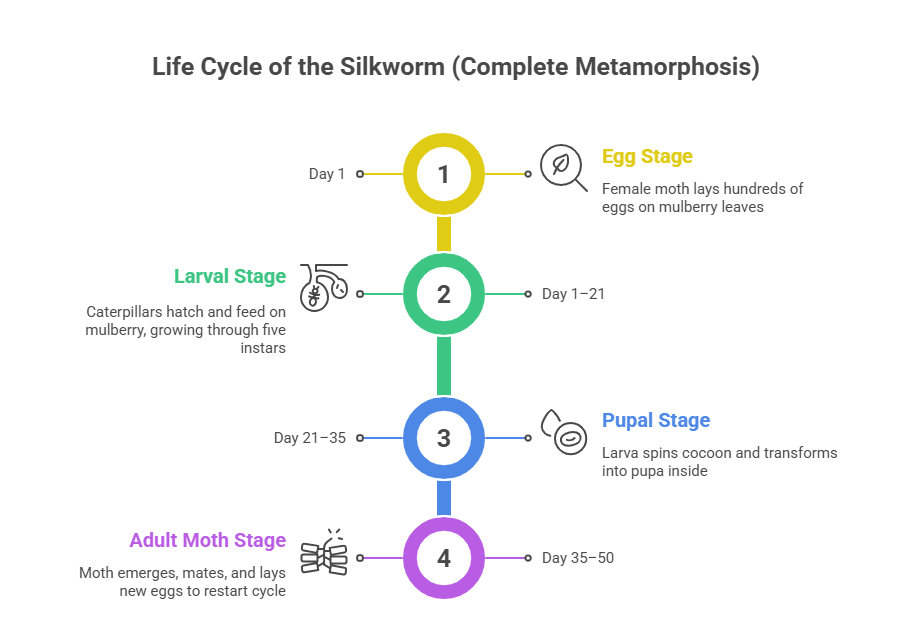

The silkworm (Bombyx mori) develops through four main stages—egg, larva, pupa, and adult moth—following a process known as complete metamorphosis. Under normal conditions, the cycle is finished in about 45 to 50 days.

Egg Stage

The cycle begins when a female moth deposits several hundred eggs, usually between 300 and 500. These eggs are kept under suitable conditions until hatching occurs. Their quality is crucial, since healthy eggs give rise to strong caterpillars that are capable of producing fine silk.

Larval Stage

When the eggs hatch, tiny caterpillars emerge. This is the longest and most active feeding stage, lasting roughly three to four weeks. During this period, the silkworms feed almost exclusively on mulberry leaves. They grow rapidly, shedding their skin four times as they pass through five growth phases called instars. The last two instars are especially important because the larvae gain most of their size and prepare for silk production.

Pupal Stage

After the final molt, the mature larva stops eating and begins producing a long, continuous filament of silk. Using this fiber, it spins a cocoon that serves as a protective case. Inside the cocoon, the silkworm undergoes its transformation into the pupal form. For silk production, these cocoons are often collected before the moth can emerge, as the fibers are most valuable at this stage.

Adult Moth Stage

Within the cocoon, the pupa eventually changes into an adult moth. To come out, the moth releases an enzyme that weakens part of the cocoon wall, allowing it to break free. Unlike the larval stage, the adult moth does not feed; its only role is to reproduce. Once mating and egg-laying are complete, the life cycle begins again.

Feeding and Caring for Silkworms

Feeding

Proper nutrition is essential for the healthy growth of silkworms and for maximizing silk output. Young larvae, commonly called Chawki, are given soft, finely cut mulberry leaves that are easier for them to chew and digest.

As they grow larger and their appetite increases, they are fed with whole, mature leaves. The leaves must always be fresh, clean, and free from moisture, dust, or chemicals, as contaminated leaves can harm the worms. Feeding is usually done three to four times daily to keep them well-nourished and active.

Bed Cleaning (Litter Management)

Maintaining cleanliness in the rearing trays is a crucial part of silkworm care. Leftover leaves, droppings (known as frass), and the skins shed during molting should be removed regularly. If waste is allowed to accumulate, it can cause poor hygiene and create favorable conditions for disease-causing organisms. Consistent bed cleaning helps maintain a safe environment and lowers the risk of infections spreading among the worms.

Environmental Conditions

Silkworms grow best under carefully regulated surroundings. The recommended temperature range is 24°C to 28°C, with humidity maintained between 70% and 85%. These conditions support healthy feeding, steady growth, and successful cocoon spinning. The rearing room should also be safeguarded against pests such as ants, flies, and other insects that might endanger the worms. By controlling these factors, farmers can achieve a better yield of strong, good-quality cocoons.

Production Season

Sericulture is not limited to one particular season; it can be carried out several times a year depending on climate and the availability of mulberry leaves. In tropical and subtropical regions, farmers are often able to rear five to six crops annually, which makes the practice highly productive.

The rearing schedule is generally planned in line with the steady supply of good-quality mulberry leaves, while also considering weather conditions. To achieve healthy silkworm growth and better cocoon yield, farmers avoid unfavorable periods such as extreme cold, excessive heat, or long stretches of dryness when scheduling their cycles.

Rearing House

The rearing house is the central facility of a sericulture farm, where silkworms are cared for from the early stages until they spin their cocoons. A well-designed and properly maintained rearing house supports efficient management, healthy larval growth, and better cocoon production.

a). Rearing Stands

Inside the house, silkworms are kept in trays that are arranged on multi-layered stands. These stands allow farmers to rear large numbers of worms in an organized way, while also making daily tasks such as feeding and cleaning easier.

b). Chandrikas (Mountages)

At maturity, silkworms need a suitable surface on which to climb and spin their cocoons. For this purpose, structures called chandrikas or mountages are provided. They are usually made from bamboo, straw, or plastic and give the worms a natural framework for producing uniform, good-quality cocoons.

c). Tools and Equipment

Several tools are required for smooth rearing operations. Trays are used to serve mulberry leaves, knives are needed to cut the leaves into small pieces for young larvae, sprayers help disinfect the rearing space, and nets are used to handle and transfer worms carefully during different stages.

d). Hygiene Station

Cleanliness is a key factor in successful sericulture. To reduce the risk of diseases, a hygiene station is often placed at the entrance of the rearing house. Here, workers disinfect their hands and feet before entering. This simple precaution helps keep the environment safe and protects the worms throughout the rearing cycle.

Silk Harvesting and Processing

a). Harvesting

The process of silk harvesting begins about 7–8 days after the silkworms have started spinning their cocoons. At this stage, the cocoons are carefully collected before the adult moth emerges. If the moth breaks out naturally, it cuts through the continuous silk filament, reducing its commercial value. Therefore, timely harvesting is crucial to obtain long, unbroken silk threads.

b). Stifling

Once harvested, the cocoons undergo a process called stifling. In this step, they are exposed to hot air or steam, which kills the pupa inside. This prevents the moth from emerging and damaging the filament. At the same time, stifling dehydrates the cocoon, making it easier to store for further processing.

c). Sorting and Cooking

The cocoons are then sorted according to their quality, size, and color. Sorting ensures that only the best cocoons are used for reeling, which improves the quality of the final silk. After sorting, the cocoons are boiled in water to soften the sericin, a natural gum that binds the silk filaments together. This softening process prepares the cocoon for easy unwinding.

d). Reeling

In the reeling stage, the softened cocoon is gently brushed to locate the loose end of the silk filament. The filament from several cocoons—usually between 5 to 10—is unwound simultaneously and twisted together to form a single, strong thread of raw silk. This is carried out on a reeling machine, which ensures uniformity and efficiency in producing continuous silk yarn.

e). Bailing

The final step in silk processing is bailing. Here, the raw silk threads are wound into skeins, bundled, and packed into bales. These bales are then sold to silk weavers, who use the raw silk for weaving fine fabrics and garments.

Common Challenges in Silkworm Farming

Common Diseases

a). Grasserie (Viral Disease)

Grasserie is a viral infection that causes silkworms to swell abnormally, eventually releasing a milky liquid from their bodies. Affected worms become weak, stop feeding, and usually die soon after showing symptoms. Since viral infections cannot be treated once they occur, prevention is the only effective measure.

Farmers are advised to maintain strict cleanliness in the rearing house, disinfect trays and tools before use, and always use disease-free eggs. Equipment and rearing stands can be treated with a 0.02% sodium hypochlorite solution to destroy viral contaminants.

b). Flacherie (Bacterial Disease)

Flacherie is a bacterial disease that results in diarrhea, sluggish behavior, and stunted growth in silkworms. Infected worms often emit a foul odor and die rapidly. To prevent outbreaks, it is important to keep rearing beds clean and dry.

If the disease appears, spraying the rearing space with a 0.02% bleaching powder solution or a 0.01% formalin solution can help control bacterial spread. A traditional preventive method involves feeding silkworms mulberry leaves dusted with a mixture of lime powder and slaked lime, which reduces the chance of infection.

c). Muscardine (Fungal Disease)

Muscardine is caused by the fungus Beauveria bassiana. It can be recognized when infected silkworms become stiff and are covered with a layer of white fungal growth. This disease spreads quickly in conditions of high humidity.

Control measures include dusting the rearing beds and nearby areas with a mixture of 2% slaked lime and 0.5% bleaching powder. In addition, spraying a 0.2% formalin solution in the rearing house after cocoon harvest helps disinfect the space and prevents future fungal infections.

Common Pests

In silkworm cultivation, pests such as uzi flies, ants, and rats can cause serious damage if not controlled effectively. Uzi flies are especially destructive because they lay eggs on the silkworms, and the developing larvae consume the worms, leading to their death.

Ants also create problems by preying on silkworms and feeding on mulberry leaves, which disrupts the rearing process. Likewise, rats harm the industry by eating silkworms as well as cocoons, which lowers both the quantity and quality of silk produced. For this reason, adopting strong preventive and pest-management measures is vital to ensure healthy silkworm rearing and to reduce losses.

Weather Fluctuations

Fluctuations in weather conditions have a significant influence on silkworm cultivation. Extreme heat, sudden cold, excessive humidity, or prolonged dryness can strain silkworms, slowing their development and weakening their resilience. Such stress not only makes them more susceptible to diseases but also affects the growth and nutritional quality of mulberry leaves, their primary source of food. When leaf quality declines, silkworm feeding and cocoon formation are compromised, leading to reduced productivity and inferior silk output. Therefore, maintaining consistent and balanced environmental conditions is essential for efficient and profitable silk farming.

Labor Intensive

Silkworm rearing requires extensive human involvement, as most stages—from mulberry cultivation and leaf collection to feeding larvae and maintaining clean rearing spaces—must be handled manually. Precision and consistency are essential at every step to promote healthy development and obtain quality cocoons, leaving little margin for mistakes. Because the process is so labor-dependent, production costs are high, and farmers often face difficulties in finding reliable and skilled workers, particularly during the busiest rearing periods.

Production Cycle

The life cycle of silkworms is relatively brief, usually spanning 25 to 30 days from the time the eggs hatch until the cocoons are formed. Based on local weather conditions and the supply of mulberry leaves, farmers are often able to rear four to six batches of worms in a single year, enabling several harvests within a short timeframe. On average, a set of 100 disease-free layings (DFLs) can produce about 35 to 40 kilograms of cocoons. With careful management, this makes sericulture a highly efficient and sustainable agricultural activity.

Yield

An acre of mulberry land can usually accommodate around 500 to 600 disease-free layings (DFLs) in a single cycle. Each cycle produces roughly 200 to 240 kilograms of cocoons. Over the course of a year, depending on how many rearing cycles are carried out, the output from one acre can range between 800 and 1,200 kilograms. With proper care and maintenance, mulberry farming proves to be a highly productive option for cocoon production.

Initial Investment / Setup

| Particulars | Estimated Cost (NRs.) |

| Purchase of mulberry saplings / plantation establishment | 25,000 – 35,000 |

| Land preparation and irrigation setup | 30,000 – 50,000 |

| Construction of rearing house (if needed) | 150,000 – 250,000 |

| Silkworm rearing equipment (stands, trays, mountages, disinfectants) | 40,000 – 60,000 |

| Total Cost | 245,000 – 395,000 |

Recurring / Operational Costs

| Purchase of silkworm eggs (DFLs) | 15,000 – 25,000 per cycle |

| Mulberry leaves (harvesting / purchasing) | 10,000 – 15,000 per cycle |

| Labor for rearing, feeding, cocoon harvesting | 25,000 – 35,000 per cycle |

| Electricity, water, and maintenance | 8,000 – 12,000 per cycle |

| Total Operational Cost | 58,000 – 87,000 per cycle |

Annual Maintenance Cost

The annual maintenance cost for sericulture farming is estimated at around Rs. 120,000 to Rs. 150,000 per acre, which covers essential expenses such as fertilizers, manure, irrigation, labor, the purchase of disease-free layings (DFLs), and disinfectants required to sustain healthy mulberry growth and efficient silkworm rearing.

Income Per Acre From Sericulture

The annual income from sericulture farming per acre is generated through the sale of cocoons, with yields ranging between 800 and 1,200 kilograms per year. At an average market price of Rs. 900 to Rs. 1,000 per kilogram, farmers can earn approximately Rs. 720,000 to Rs. 1,200,000 annually from a well-managed mulberry plantation and silkworm rearing system.

Profit Analysis of per Acre Sericulture Farming

The profit analysis of sericulture farming shows that after deducting annual maintenance and operational costs, farmers can earn a net profit of approximately Rs. 550,000 to Rs. 1,000,000 per acre each year. With such strong returns, the initial investment is usually recovered within 1 to 2 years, resulting in a high return on investment (ROI) ranging from 150% to 250%, depending on yield performance and prevailing market prices.

Sources

Ganga, G., & Sulochana Chetty, J. (2008). An Introduction to Sericulture. Oxford & IBH Publishing.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Sericulture Manuals.

Central Silk Board (CSB), India. (Various publications).